I first heard “Heed the Call” the way many great songs show up—half by accident, half by fate—on a quiet night when distant traffic sounded like rolling tape. The vocal came in warm and sure, with harmonies stacked in confident tiers, and the message was unmistakable: rise up, link arms, do the decent thing. Even without knowing its release date, you can feel its era. This is late 1970 America, where a chorus can double as a town hall.

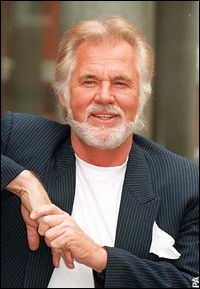

Kenny Rogers & The First Edition put this one out during a concentrated burst of creativity. By then, the group had already crossed from psychedelia-tinged pop into country-rock and storyteller balladry, earning space on radio playlists that didn’t often mingle. “Heed the Call” arrived as a single from their 1970 Reprise LP Tell It All Brother, a record produced by Kenny Rogers with Jimmy Bowen, and arranged in places by Larry Cansler for strings—details that help situate the track’s blend of punch and polish. It moved on the pop chart as a bona fide Top 40 entry, the sort of performance that signals a song traveling across formats as much as across state lines. Wikipedia+1

One reason it works: the writing. Credited to Kin (Charles K.) Vassy, “Heed the Call” compresses the sentiment of community into a framework that invites group singing without lapsing into sloganeering. The lines land with the clarity of a banner and the cadences of a campfire hymn. That’s a narrow ridge to walk, and the group keeps their footing. The hook doesn’t shout at you; it beckons.

Listen closely to the arrangement and you’ll hear a band fluent in dynamics. The rhythm section moves with a pulse that’s neither rock-club aggressive nor church-choir restrained. Drums sit forward enough to give urgency, yet they never bulldoze the vocal blends. Electric bass places the downbeats like guideposts, slightly rounded at the edges, so the whole track breathes rather than hammers.

This is also a harmony showcase. Rogers’ lead sits at the center—gravel-and-velvet, patient on the verses—while the First Edition’s voices knit around him in luminous thirds and fifths. The sound is closer to a civic chorus than a star-and-sidekicks arrangement. When the hook repeats, you can hear the slight lift in the upper voices, a gentle tilt that makes the refrain feel like a field being swept by light. It’s the kind of detail you catch when you lean in with good studio headphones, and the payoff is how the overtones seem to bloom after each phrase.

Texturally, “Heed the Call” splits the difference between folk-country earthiness and radio-friendly sheen. Acoustic strums provide a steady grain beneath the band; hand percussion and tambourine flicker at the edges; a restrained backline adds contour without stealing focus. If you imagine the mix on a physical board, the fader on “drama” is set to medium—never hushed, never bombastic.

You could call this a civics lesson disguised as a singalong, but that undersells the craft. The verse melodies carry enough contour to feel like small journeys, while the chorus—short, memorable, generous—wins you over with repetition that never grates. There’s also a gentle gospel aroma in the block harmonies, suggesting the Sunday-morning lift that popular music in 1970 often borrowed to make Saturday-night radio feel like an open door.

Context is essential. Tell It All Brother, the LP that houses “Heed the Call,” came out in November 1970 on Reprise, with Rogers increasingly asserting himself not just as a frontman but as a studio decision-maker. That period—framed by earlier singles like “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town” and “Something’s Burning”—shows a group reshaping their identity after the psychedelic spark of “Just Dropped In.” “Heed the Call” fits that arc perfectly: it’s earnest without being stiff, pragmatic in tone, and universal in aim. Wikipedia

Part of the track’s appeal is tactile. The snare has a crisp, papery attack, like a quick page turn. The bass sustains just long enough to round each measure. Guitars—clean, slightly chorused or doubled—trace the chords with friendly insistence rather than flash. When a keyboard colors the harmony, it’s more supportive than declarative; a piano figure appears like a helping hand, not a spotlight grab. Nothing in the mix feels airless; there’s room reverb that lets the voices and percussion breathe, as if captured in a space designed for togetherness rather than isolation.

That spatial sense helps explain why the refrain lands as an invitation. The recording isn’t purely dry and tight; nor is it drenched in echo. Instead, it carries a modest ambience that sets the listener just a few rows back from the singers, near enough to feel the breath, far enough to sense the room. That balance is production wisdom: bring the audience inside, but don’t erase the air between people. Jimmy Bowen had a knack for commercial clarity, and Rogers’ instincts toward narrative shape ensure the parts serve the message. Wikipedia

I’ve always loved how the lyric finds dignified urgency without dressing itself in panic. “Heed the Call” implies consequence, but the mood is constructive, persuasive. The verses frame the stakes; the refrain offers the path. It’s the difference between a scolding and a summons. In 1970, that tone must have felt like a relief—especially in a year buzzing with broadcasts that often sounded like alarms.

Here’s a small listening exercise: focus on the consonants of the group vocal near the end. You’ll notice how the “h” in “heed” leaves a soft exhale before the vowel blooms, and how the “l” in “call” is held just a fraction longer than speech. Those choices turn language into rhythm. This is where communal singing lives—at the seam between text and time.

You also hear the band’s restraint. There’s no gratuitous soloing, no attempt to turn a community anthem into a virtuoso spotlight. If a lead line peeks out, it’s to underline the harmony rather than to eclipse it. That’s discipline, and it pays off: the song feels shorter than it is because nothing distracts from the arc.

I’m cautious about claiming precise studios or session minutiae without documentation, but what is clear is that “Heed the Call” bears the fingerprints of its credited team. Rogers and Bowen tended to value intelligible vocals and radio presence; Larry Cansler’s hand with strings on the LP favors supportive swells rather than syrup. The record’s chart action in the Top 40 suggests that radio programmers heard an anthem that could sit beside AM gold without sounding preachy, which is its own kind of miracle at the end of a turbulent year. Wikipedia

Micro-stories often prove a song’s staying power. A friend of mine once played “Heed the Call” over a slideshow at a neighborhood fundraiser; by the second chorus, people who hadn’t met before were singing harmonies as if they’d practiced. Another time, I watched a college class—most students born decades after 1970—snap into focus the moment the refrain hit. They didn’t know the backstory, but they recognized the posture: show up, help out, hold the line. And a late-night DJ told me he keeps it cued for snowstorm coverage, because it frames the news with calm resolve rather than sirens.

What about the song’s timbre in modern listening environments? On a modest living-room setup, the blend remains clear and inviting; if you step up to more revealing premium audio, the inner lines of the harmony and the crispness of the percussion come forward, especially around the upper-mids where the voices paint their vowels. The record’s age doesn’t hinder its presence; instead, the slightly analog patina warms the edges, trading hyper-detail for human texture.

“‘Heed the Call’ doesn’t preach from a pulpit—it speaks from a porch, making moral courage sound like something ordinary people can do together.”

That porch image extends to the song’s structure. There’s a welcoming front step in the intro, a hand on the shoulder in the verse, and a larger circle of neighbors every time the chorus returns. The pacing keeps each section short enough to feel like a breath, long enough to gather everyone’s voice. The fade—if you’re hearing the single mix—feels like a crowd still singing as you walk away.

Because the track sometimes shows up on later compilations, listeners occasionally mistake it for a solo Rogers cut from the mid-to-late 1970s. It isn’t. It belongs to the First Edition era, reflecting a band identity even as it foreshadows the steadiness that would define Rogers’ solo hits later in the decade. On some reissues and digital platforms, you’ll find the credit reading “Kenny Rogers & The First Edition,” sometimes with composer Kin Vassy noted; either way, the shared identity matters: this is a group sound with a single leader, not a soloist with a backup choir. Apple Music – Web Player+1

There’s also a fun discographical footnote: the track appears in the sequencing of Tell It All Brother, which itself sits between other First Edition releases from 1970 and 1971—a remarkably productive window. Hearing the LP straight through, you notice how “Heed the Call” answers the title track’s confessional tone with a more communal register, as if telling the truth is step one and showing up is step two. That pairing gives the record a conceptual spine without turning it into a concept album. Wikipedia

I sometimes think of “Heed the Call” as a civic carol. Not because it mentions holidays or seasons, but because it carries the same ritual invitation: gather, sing, remember who you are to one another. In an era when playlists atomize attention and our feeds organize us into ever smaller rooms, this piece of music suggests a larger table. Its craft—the contour of the melody, the balance of the mix, the measured propulsion of the backing band—keeps that table sturdy.

Let’s talk instruments briefly, not to pin every note to a diagram but to sketch the palette. A steady strum anchors the harmony on guitar, while subtle keyboard cushioning—occasionally a piano accent, occasionally a sustained pad—provides glue. Drums and bass offer motion with minimal fuss: no flams for drama’s sake, no double-time for empty adrenaline. If there are strings in your version, they behave the way good string parts do in popular records of this era: they arrive to widen the horizon rather than to add perfume.

Listeners who come to Rogers expecting only the gambler’s wink or the story-song twist might be surprised by the steadiness here. The narrative isn’t about a drifter, a card table, or a grand reveal. It’s about the small heroism of participation. The way the voices meet at the center underlines that message. Harmony, in the literal sense, becomes the argument.

And that may be why “Heed the Call” has aged well. While some topical songs collapse under the weight of their moment, this one abstracts just enough to cross decades without losing its point. You can put it between contemporary tracks in a setlist themed around community, or you can wedge it between classics from the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, and it will sound like it belongs. It’s not the loudest record of 1970, nor the most ornate, but it’s one of the most useful—useful in the sense that it offers a workable posture for ordinary life.

As for practicalities, anyone wanting to sing it with friends will find the structure forgiving and the range welcoming. Simple chords, clean melodies, room for unison and harmony alike. You don’t need formal guitar lessons to carry the bones of it, though anyone with arranging instincts will enjoy thickening the lines for a larger group. And if you want a deeper dive, pull up the track on a music streaming subscription and A/B it against other First Edition cuts from the period. You’ll hear how the group toggled between intimacy and uplift with surprising economy.

In the end, the mark of a durable single is whether it can absorb new circumstances without breaking. “Heed the Call” does that. It keeps its shape while accepting our own times into its frame. When the refrain returns, the invitation remains fresh: do the next good thing, with whomever is beside you. That’s not just nostalgia; it’s instruction—quiet, steady, and still useful.