There’s a soft hush at the edge of this record—the kind of hush you hear when tape begins to roll and a singer steels himself for a truth he can’t avoid. In my mind’s ear the room is small, a lamp left on, a chair pulled closer than usual, and the first chord is struck with the care you reserve for a breakable thing. That’s the mood “For the Good Times” invites, even before a voice enters. The song offers no fireworks; it tilts toward you like someone about to say the one thing they wish they didn’t have to say.

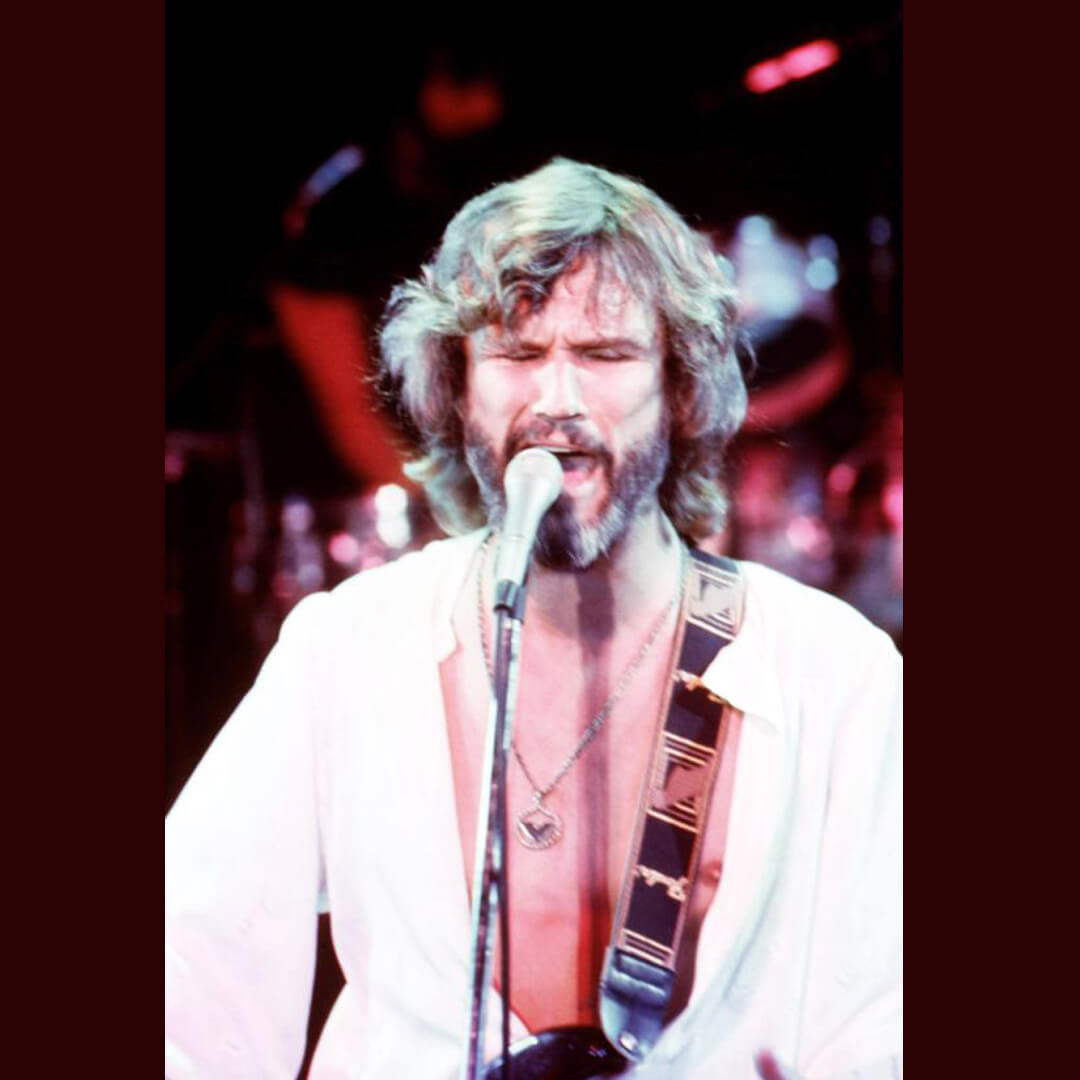

Kris Kristofferson recorded “For the Good Times” for his first Monument Records album, a 1970 release simply titled “Kristofferson,” produced by Fred Foster. It’s a crucial waypoint in his early career—a period when he was known in Nashville as a songwriter’s songwriter, handing other artists tunes that took them to the charts while he built a reputation for literate, unvarnished storytelling. Ray Price would soon transform this piece of music into a major country hit, carrying it beyond the genre’s borders, but Kristofferson’s own cut is the seed from which that bloom grew. Hearing his version now is like reading a first edition you once knew only from the glossy coffee-table reprint.

What sets his recording apart isn’t just authorship; it’s temperature. The arrangement is modest and unhurried. You can pick out the acoustic guitar at the center, not flashy, never calling attention to itself, just the steadying pulse of someone trying to keep their hands from shaking. A quietly supportive piano line arrives like a friend who sits beside you and decides not to fill the silence. The rhythm section—bass and brushed drums—breathes rather than drives. If there are small ornaments, they behave like good listeners: they leave room.

Kristofferson’s vocal sits low and close. He doesn’t chase the high notes other interpreters would later claim; he leans into phrasing instead, letting ends of lines fray slightly, allowing breaths to show. The song asks for steadiness but admits tremble. He gives it both. One can imagine a single microphone in a space that doesn’t fully absorb the air; you hear a light halo of room around the voice. There’s a humility to the sound, an unvarnished quality that was already becoming rare in a Nashville moving toward strings and satin. His restraint is a choice, and it suits the lyric like a well-worn jacket.

“For the Good Times” is, at heart, a negotiation with goodbye. Most breakup songs beg or lash out. This one tidies the table and turns off the light. Its narrator does not accuse; he arranges. He offers a last night together, not out of desperation but out of tenderness, asking for gentleness in the face of something inevitable. The song’s moral center is mercy—the mercy to end without cruelty, to acknowledge love’s worth even as it fails.

The words carry that mercy without ever softening into sentimentality. Kristofferson writes with the clarity of someone who has rehearsed this moment while walking alone, perhaps at dawn when ideas arrive honest and bare. The lyric moves by plain images and everyday verbs: hold, don’t cry, close the door softly. The lack of ornament is the ornament. That’s why the melody can be so direct. It’s country music, yes, but it’s also conversational poetry—phrases that balance on the edge of spoken cadence and find a melody only when they must.

I think often about the difference between restraint and denial. The first honors feeling by steering it; the second smothers it. Kristofferson chooses restraint. You hear it in the way the chorus rises only a half step’s worth of drama, then returns to the verse like someone folding a letter and slipping it back into the envelope. What stays with you isn’t a spectacular high note but a line reading—how he lets a vowel linger, how he shortens a consonant to keep from letting it sound like a final blow. He understands that emotional closure is not the same as a slammed door.

“Some songs are good company; this one is a good goodbye—present, unflinching, and kind.”

Part of the song’s mythology rests in its second life. When Ray Price recorded it, he draped it in velvet—strings that breathe, a glide in the tempo, a classic-country croon that turns the lyric’s quiet courtesy into ballroom grace. That version crossed over for a reason: it carries the assurance of an adult who knows how to leave the dance floor with dignity. Kristofferson’s original is smaller in scale and, to my ears, more vulnerable. The distance between the two interpretations illustrates how robust the writing is. The core of the song can withstand different rooms, different lights, and different singers’ masks.

Listen to the Kristofferson cut with attention to the small dynamics. The verses don’t just proceed; they gather. When the bass nudges a change, it does so with the intuition of a seasoned player who understands that intensity can be felt as an inch rather than a mile. The brushwork on the snare has a human sway—tiny shifts in pressure, a soft swell into the chorus. You could mix it louder and call it drama, but its modesty is its realism. This was always a living-room song, written by a man who knew that heartbreak rarely announces itself with brass.

Guitar and piano also define the song’s emotional geometry. The guitar’s role is to hold the center—little arpeggios, a few linking runs across chord changes that suggest acceptance rather than flourish. The piano, meanwhile, handles the peripheral vision: spare voicings in the middle register, gentle thirds and sixths that color the harmonic plain without dressing it up. If this were a portrait, the guitar would be the sitter’s posture; the piano would be the light from the window.

The lyric’s plainspokenness invites listeners’ lives inside. Over the years I’ve watched the song accompany three kinds of departures. First, the late-night radio exit—highway empty, dashboard glowing, the kind of drive where you think you’re outrunning a decision until the chorus reminds you you’ve already made it. The music catches the rhythm of tires on a long straight, and something in the way Kristofferson shapes the lines lets you rehearse the goodbye without saying it out loud.

Second, the kitchen-at-dawn goodbye—two mugs cooling, a note written and rewritten, the sun not yet a fact. The quiet of “For the Good Times” suits that scene because it doesn’t confuse intimacy with volume. It gives you instructions: don’t cry, hold each other, make this last hour a soft one. Songs often try to save us from the thing itself; this one helps us do it well.

Third, the modern text-message coda—threads half-silent, the unsent message reading like a prayer. In an age of instantaneous replies, the song’s patience is radical. It lingers on the margins, suggesting that a clean farewell may require ritual: a final meal, a night on the couch, a last look around the rooms you filled together. The melody doesn’t hurry you out. It allows a few beats of stillness you can climb into.

Though the Kristofferson recording is lean, the composition welcomes larger frames. That’s part of why it traveled so widely. Al Green found the soul vulnerability inside it; other singers heard torch-song potential or country-pop polish. You can take the harmonies to a lusher place without betraying the core, or you can keep it stark and let the floorboards creak. The architecture is versatile enough to bear different paint colors.

From a craft perspective, notice the balance between repeated phrases and one-time turns. The chorus functions as a promise, not a slogan. It returns with slight emotional readjustments depending on how the verse lands. The bridge (or the moment that feels like one) doesn’t explode; it offers a second angle on the same truth, a gentle feint that avoids dramatics. You’re reminded how often great country songs are built: not with pyrotechnic chord changes, but with patient, inevitable movement.

The production choices on Kristofferson’s debut mean you hear the air between instruments. This matters. The space becomes a character, like the pause in a conversation where both people decide whether to ask one last question. The overall timbre leans warm and human; nothing metallic, nothing brittle. You can imagine listening on a modest turntable in a quiet apartment, hearing the soft grain of the voice and the way the consonants land. It’s a recording that rewards close listening on good studio headphones, though its humility plays just as well through a single speaker in the corner of a room.

Because the song now lives in the American canon, it’s easy to forget how radical its kindness was in 1970. Country music, like any genre, has its share of vengeance and regret. Kristofferson wrote a goodbye that refuses to injure. It honors what was shared even as it acknowledges that it’s over. In that sense, the track aligned perfectly with his emergent artistic persona: the Rhodes scholar with a janitor’s keys, the poet who could write like a neighbor. On the “Kristofferson” album he toggled between road-weary narratives and intimate meditations; “For the Good Times” is one of the quiet pillars holding that house up.

If you’re looking to play it yourself, you’ll find that the tune sits in an approachable range with changes that feel familiar under the fingers, one reason it appears in so much sheet music across genres. It’s a classic country progression rendered with folk instincts—more about voice-leading than showcase, more about honesty than surprise. Singers learn quickly that the song reveals them. You can’t hide in it; you can only be proportionate to it.

I sometimes think about this recording as a letter placed in a drawer rather than mailed. It’s addressed to someone specific, but it also speaks to anyone who’s had to make the merciful version of a hard choice. The notion of keeping “the good times” doesn’t sugarcoat; it archives. There’s a librarian’s ethics to the lyric: label what was beautiful and put it where you can reach it without reopening the wound. In an era of maximal confession, that level of composure feels almost radical.

There’s also the matter of time. Songs like this age in two directions. They become historical artifacts—markers of a sound and an ethos from Nashville at the turn of the decade—and they become mirrors that look more accurate the older we get. With each passing year, the song’s tone of gentle parting reads less as youthful romance and more as adult practice. It’s not a teenage catastrophe; it’s a quiet rerouting of two lives with gratitude intact.

You can, if you want, turn up a modern cover on your favorite music streaming subscription and admire the polish. But returning to Kristofferson’s own take feels like walking back to the source of a river after seeing it run through a city: the water is colder, the banks are smaller, and the sound is uncomplicated in the best way. The economy of the performance is not minimalism for its own sake; it’s fidelity to feeling.

As for the legacy, it’s broad but not flashy. You can cite how often the song has been covered, how far it strayed from the honky-tonk into lounges and living rooms, how it helped cement Kristofferson’s reputation as one of the era’s most important writers. You can name producers and labels, remember that Fred Foster had the ears to let the song breathe, recall that Monument gave a platform to a writer who’d soon become a household name. Those are the facts. The deeper truth is that the track still does its job: it softens the hardest hour without pretending it isn’t hard.

Re-listening today, what stands out most is the balance it achieves between intimacy and universality. It feels like a private conversation you’re permitted to overhear, yet its lines are portable enough to hold your own experience. That’s a rare feat. It’s also why the song belongs to the larger story of American songwriting as much as it belongs to any particular singer’s discography.

If you haven’t revisited Kristofferson’s original in a while, do it with a quiet room and maybe a light low in the corner. Let the first chord settle. Hear how the arrangement walks instead of runs. Listen to how the voice holds steady without pretending to be strong. And when it ends, notice how you feel—a little sad, yes, but steadier, as if someone taught you a graceful way to place the past where it belongs.

The goodbye at the heart of “For the Good Times” still matters because it models a kind of care we rarely hear amplified. That care is the song’s entire point—and its enduring gift.

Listening Recommendations

-

Ray Price – “For the Good Times”

For the same lyric draped in countrypolitan silk; strings and croon turn mercy into ballroom grace. -

Sammi Smith – “Help Me Make It Through the Night”

Another Kristofferson masterwork, intimate and nocturnal, where hushed production meets open-wound honesty. -

Willie Nelson – “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain”

Sparse arrangement and quiet vocal that make heartbreak feel like a whispered confession. -

Eddy Arnold – “Make the World Go Away”

Gentle countrypolitan sweep that pairs orchestral warmth with stoic, adult resignation. -

Al Green – “For the Good Times”

A soul reading that finds new tenderness in the melody, all velvet phrasing and patient groove. -

Willie Nelson – “Funny How Time Slips Away”

Elegant conversational songwriting with a wry smile, living in the same slow-turning hourglass of goodbye.