The late-night radio hums a low, golden frequency, the kind of static-kissed sound that feels less like transmission and more like a shared secret. Maybe you’re alone in a pickup, maybe leaning against a kitchen counter at 2 AM, the world asleep outside the frame. That is the perfect venue for Kris Kristofferson, and it is precisely where a piece of music like “Jody And The Kid” thrives. It is a song that does not announce its sadness; it merely invites you to sit in the quiet aftermath of it.

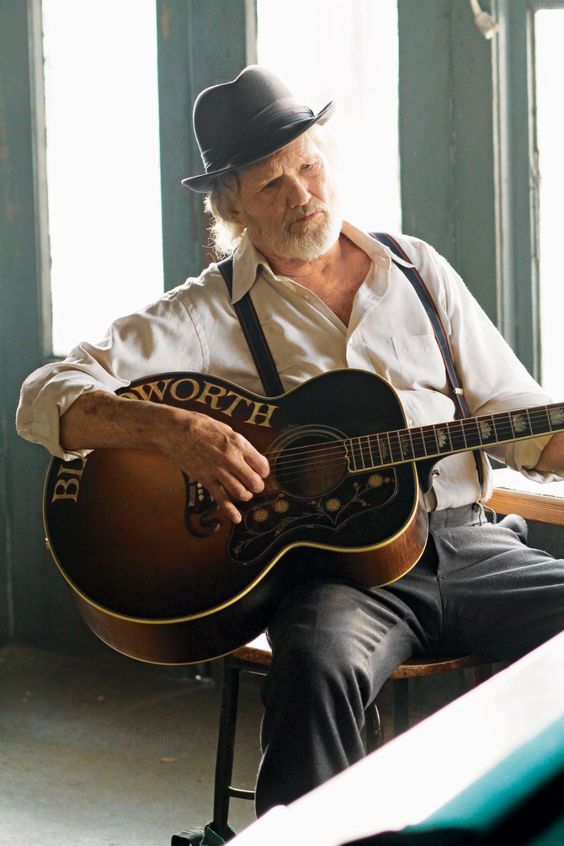

Kristofferson, the Rhodes Scholar turned janitor turned Nashville revolutionary, wrote the song during the incandescent flash of creativity that defined his late twenties. Before he became the reluctant movie star and the establishment’s favorite counter-culture icon, he was simply the writer, the lyrical architect building entire worlds in three verses and a chorus. This particular song was penned early, in the era when he was scraping by, waiting for giants like Cash and Waylon to validate his craft by recording his material.

Roy Drusky recorded it first, in 1968, taking it onto the charts and inadvertently funding Kristofferson’s janitorial tenure at Columbia Studios. But it is Kristofferson’s own recording—released in 1971 on his second major-label full-length, The Silver Tongued Devil and I—that serves as the definitive, dust-caked blueprint. This album, produced by Fred Foster on the Monument label, cemented Kristofferson’s transition from a revered songwriter to a compelling, flawed performer, placing “Jody And The Kid” right in the heart of his early, crucial canon.

The Arrangement: Honesty in the Grain

The track’s sound is a masterclass in controlled melancholy. It opens not with a flourish, but with the dry, deliberate strum of an acoustic guitar, soon joined by a subtle bass line that anchors the narrative. The genius of the arrangement lies in its economy. Nothing is wasted. The entire song breathes with a room-mic authenticity, suggesting a small, intimate ensemble playing close together, committed to supporting the song, not showcasing their chops.

Kristofferson’s voice, a weathered baritone that always sounded like it was coming from the next town over, is front and center. His phrasing is conversational, almost mumbled in places, making the listener lean in to catch the punchline, or in this case, the heartbreak. He sounds like a man trying to explain a lifetime in a few minutes, struggling for the right words, even though the words are perfect.

As the story progresses, a delicate piano enters the mix. It’s not a showy presence, just a few clean, high notes that chime in like a memory suddenly crystalized. There is a faint, sweeping wash of strings—violins and maybe a cello—but they are mixed far back, providing emotional texture rather than orchestral melodrama. They suggest the swelling ache of nostalgia, kept just beyond the narrative foreground. The dynamic restraint is crucial; it elevates the song’s intimate storytelling far beyond typical 1970s country-pop production. This sonic subtlety is something lovers of premium audio systems often chase, as the track’s layers reveal themselves best on well-calibrated speakers.

The Geography of a Fading Love

The narrative itself is pure Kristofferson: cinematic, deeply felt, and morally complex. It tells the story of a man—the “Kid”—and a little girl, Jody, who follows him around in his youth. The older boy finds the child’s adoration comforting, a simple, pure connection untouched by adult anxieties. He relishes the simplicity of their friendship: a reliable, innocent presence in his otherwise rambling life. The lines paint a tangible world: “Lord, I really loved that Jody and the kid.”

But the passage of time is the true antagonist here. Jody grows up. The narrator notices the change, the burgeoning womanhood that replaces the worshipful little girl. The simple dynamic warps. The transition is handled with a devastating lyrical brevity: “And the Kid found out she meant it when she told him, ‘Boy, it’s only fair that you be gentle.'” Suddenly, the innocent tag-along is a woman demanding respect, demanding a different kind of relationship. The gentle, melancholic swing of the tempo underscores the quiet inevitability of this transformation.

The final verses deliver a punch that lands with soft cruelty. The Kid—now an adult himself—is looking for love in a bar one night, and he sees Jody with another man. Not only that, but they are leaving a child with a sitter. Jody is married, a mother, and still, ironically, the narrator’s old nickname is what pierces him. He overhears someone say, “Looky yonder, there goes Jody and the Kid.” The label is still accurate, but the people it describes are strangers now, having built the life he, the original “Kid,” was too restless or too immature to claim.

“The power of this song rests not in an angry confrontation or a sweeping declaration, but in the quiet sting of a misplaced nickname heard across a crowded, boozy room.”

The song’s resolution is not dramatic, but deeply lonesome. The narrator retreats, realizing his own lost moment. He had the chance, the time, the emotional connection, but he failed to step up and meet the adult reality of Jody’s affection. That final, lingering image—the man left alone in the bar with his beer, forever haunted by an epithet that no longer belongs to him—is what elevates this simple country song to genuine art. It’s a gut-check on arrested development, a gentle yet devastating look at how we often miss the best things while waiting for something more dramatic to happen. For any budding songwriter struggling with the technical architecture of emotional impact, a careful study of this song’s structure could be more valuable than a dozen guitar lessons.

“Jody And The Kid” is the kind of profound, narrative songwriting that defined Kristofferson’s label. It’s a tragedy told with a shrug, an aching recollection delivered with a voice that suggests the pain has long since settled into permanent scar tissue. It reminds us that sometimes, the sharpest agony is simply hearing your past—and your potential future—walking away from you without even noticing you’re still there. It’s a masterclass in understatement that demands to be heard again, maybe even louder this time.

Listening Recommendations

- “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” – Kris Kristofferson: For the same cinematic detail and lived-in, melancholic vocal delivery.

- “Pancho and Lefty” – Townes Van Zandt: Shares the genius of telling a complete, devastating narrative in just a few sparse verses.

- “Hello In There” – John Prine: Captures a similar sense of time’s toll and the quiet observation of lives fading and changing.

- “Me and Bobby McGee” – Kris Kristofferson (or Janis Joplin): Another Kristofferson classic focused on life on the move and the bittersweet nature of temporary connections.

- “The Pilgrim: Chapter 33” – Kris Kristofferson: Offers a broader, self-reflective view of the kind of rambling man who would let a girl like Jody slip away.

- “Coat of Many Colors” – Dolly Parton: A song that similarly uses nostalgic, childhood memories to deliver a deep emotional core.