Kristofferson recognizes that artists like Emmylou Harris are essential to the preservation of country music’s integrity. She has been a bridge between generations, introducing younger audiences to the greats who came before, while giving them permission to create something fresh and honest. Her collaborations, her willingness to share the spotlight, and her dedication to the music rather than her own ego have earned her not only critical acclaim but the deep and lasting respect of her peers—including Kris himself. For Kris Kristofferson, Emmylou Harris is more than just a fellow performer; she is a standard-bearer for everything worth cherishing in country music. Her commitment, authenticity, and artistry embody the very ideals he has always believed the genre should stand for—a living proof that music with heart will always outlast the noise.

Introduction

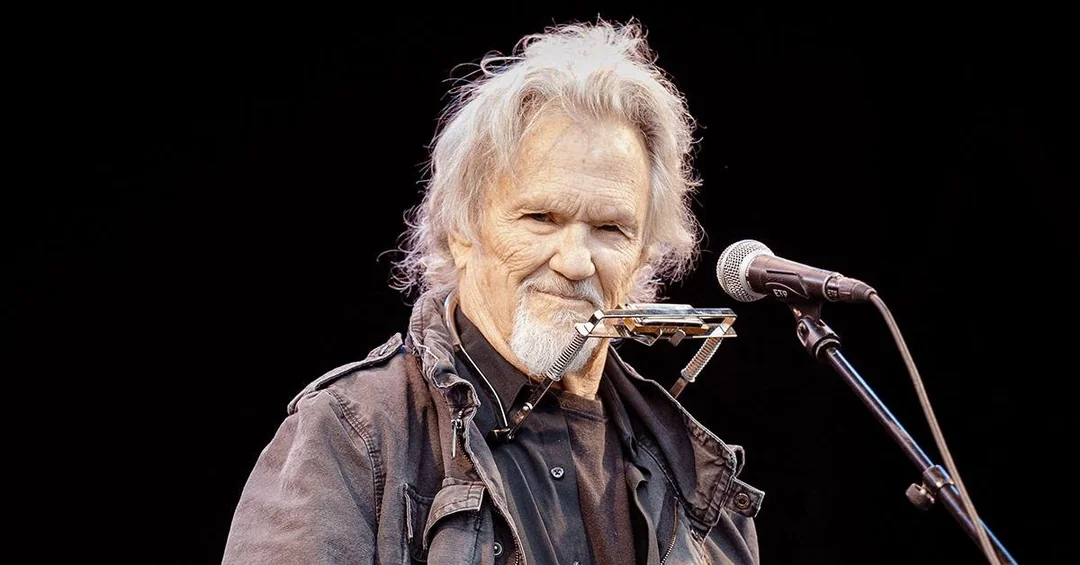

I didn’t first meet “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33” in a record store or on a jukebox. I met it in the soft blue light of a late-night living room, that hour when the day loosens its grip and the stories we’ve carried finally step forward. The screen showed Kris Kristofferson beside Emmylou Harris at a tribute concert, two lifetimes of songs pooling at their feet, and when the first line landed—half spoken, half sung—it felt less like a performance than a confession overheard. The room between their voices became a corridor you could walk down, the kind that leads you back to your own past.

The studio origin of this song matters. “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33” first appeared on Kristofferson’s second studio album, The Silver Tongued Devil and I, released in July 1971 on Monument Records, produced by Fred Foster. It’s a record that sharpened his reputation as a songwriter who could leave a bruise with a single, unadorned phrase. The song’s character—a drifting, contradictory seeker—belongs squarely to that era’s fascination with self-invention and wreckage, yet the voice is unmistakably Kristofferson: tender without pleading, stoic without armor.

The performance with Emmylou Harris that many listeners now pass around online is part of a much later celebration: The Life & Songs of Kris Kristofferson, a Blackbird Presents project filmed in Nashville and released in 2017 across broadcast and audio formats. In that setting, “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33” becomes not just a song but a summation—a veteran artist revisiting one of the truest mirrors he ever held to himself, with Harris standing alongside as both witness and equal.

There’s a subtle shift that happens when a song leaves the confines of a studio and learns to breathe in a hall. The original track from 1971 sat within a fabric of country instrumentation—plainspoken but carefully framed; the tribute rendition, by contrast, carries the warm air of a big room and the intimacy of two voices who know how to leave space for each other. You hear the blend before you identify the parts. What sounds like a small ensemble gives the tune its sway—steady percussion, bass anchoring the heartbeat, and acoustic figures sketched on the guitar, possibly a whisper of steel in the overtones. Nothing clamors for attention. Everything moves with the grain of the lyric.

Harris’s entrance is a masterclass in restraint. She doesn’t echo Kristofferson so much as steady him, finding the harmony line that softens the gravel without sanding it away. Her vowels linger just a hair longer, a faint glow at the edges of the phrase. When the camera frames them together, the contrast is visual and musical at once: hewn oak and bright glass, each making the other legible.

This piece of music lives on micro-gestures: the way Kristofferson clips the end of a line to land emotion instead of emphasizing rhyme; the low breath before Harris takes a tail note and turns it into a handhold for the next section; the balance between speech cadence and melody. If you listen on a quiet night, perhaps with decent home audio, you can catch the little reverberant stutters riding the hall—tiny reflections that reinforce the song’s sense of time passed and time passing.

What strikes me on repeat listens is how the arrangement trusts silence. The band never crowds the lyric. The guitar outlines rather than asserts; the piano—if present at all in this specific performance—stays ghostly, its role more about shade than spotlight. And yet, you can imagine how the piano would sit if you played it yourself: soft-left hand patterns tracing the chord bed, right-hand grace notes timed to breathe with the vocal. Kristofferson has always understood how to make accompaniment feel like road dust on the boots rather than decoration on the coat.

There’s also the matter of narrative authority. On the 1971 album, Kristofferson was still near the beginning of his recorded arc, delivering a portrait of a man who believed, perhaps too fiercely, in his own myth and ruin. Decades later, the same words sound less like bravado and more like inventory. The pilgrim he describes is no longer an abstraction. He’s a composite of peers, influences, and the songwriter himself—a recognition the album notes explicitly nod toward when listing the artists who animated his thinking at the time. The song even made its way into the 1972 film Cisco Pike, a reminder of how deeply that archetype—restless, haunted, romantic—had lodged in the culture of the moment.

“Performance” is the wrong word for what Harris adds in the tribute version. It’s closer to an intervention in tone—firm but affectionate. On a line that could tilt toward self-myth, she gives it ballast. On a line that risks bitterness, she adds air. The vocal chemistry doesn’t announce itself with big stacked harmonies; it settles into a frictionless fit, a decision that keeps the song’s moral weather—equal parts rue and mercy—intact.

I kept thinking of three small scenes while listening back:

A friend in his fifties, long retired from touring, once told me he can only listen to this song when the house is sleeping. “It tells the truth in a way I’m not ready for at noon,” he said, and laughed, but the laugh didn’t erase the weight of it.

A young songwriter I know—voracious reader, perpetually broke—learned “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33” as a kind of personal riddle. He plays it for open-mic crowds who don’t know the history, then watches the room grow still at the exact moment the mask slips and the man in the song stops posing and starts telling the truth.

And me, once again back in that blue-lit living room, noticing how the camera lingers on Harris’s face while Kris leans into a line, like the director knows we need to read her listening as much as we need to hear his singing. It’s a simple shot. But it confirms what you sense: that two artists are treating the song not as a relic but as a living document.

The lyric’s architecture is classic Kristofferson. He stacks archetypes—poet, picker, prophet—then dismantles them, itemizing the cost of wearing those skins in public. Even if you’ve never slept on a friend’s floor after a bad gig, you recognize the psychology: the person who confuses momentum for purpose, the person who mistakes hunger for virtue. In that way, the song keeps renewing itself for each generation that discovers it. Every era has its pilgrims; every era has its Chapter 33.

From a purely sonic angle, notice the engineering choices in the tribute capture. The close mics on the voices feel dry enough to register grain, but the room bloom creeps in on the decays, especially on held harmonies. The dynamic range stays conversational—nobody pushes for spectacle. If you happen to wear studio headphones, you’ll catch how the vocal blend thickens in the center while the acoustic strums feather outward, giving the mix a gentle oval shape. That shape is key to the performance’s calmness; it’s a canvas, not a cage.

The moral question at the heart of the song—what do we owe to the lives we invent for ourselves?—tracks differently across time. When Kristofferson first recorded it in 1971, the question met an audience still enthralled with the outlaw-as-hero narrative. Over the decades, the tenderness has moved to the foreground. You hear less swagger and more care, especially in Harris’s presence. The pairing makes the song feel not just self-aware but community-aware: a portrait of how our stories are held by others even when we can’t hold them ourselves.

One detail worth remembering is how thoroughly “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33” sits within Kristofferson’s broader catalog of self-scrutiny and witness. Alongside “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” and “Why Me,” it completes a kind of triptych: fatigue, faith, and the cost of the road. Critics have repeatedly ranked it among his essential songs, and not because it’s flashy, but because it tells hard truths without theatrics. Even The Guardian’s retrospective on his greatest work singles it out for that “calling” quality—the way it frames a musician’s life as both destiny and burden, with a songwriter’s promises as collateral.

If you chase the song’s afterlife, you find the Blackbird Presents release framing it as a keystone of the 2016 Nashville tribute—broadcast by CMT and issued on CD/DVD and digital formats in 2017. The liner and platform credits confirm that the track appears as a live cut featuring Harris and Kristofferson together, a perfect recontextualization: the man who wrote the map singing it with an artist who’s spent decades navigating similar roads.

Part of the mystique comes from the way the melody holds steady while the meaning migrates. Kristofferson’s voice has deepened into a rougher instrument, and Harris’s timbre has become, if anything, more transparent. The friction between roughness and clarity creates a natural chiaroscuro. The listener doesn’t need overt dynamic peaks; the tension resides in who’s carrying the weight of each word at any given moment.

And then there’s the quiet craftsmanship. The melodic contour is modest, almost conversational, which is precisely why the narrative lands. One could imagine a young player learning it on a back-porch guitar in the same afternoon they first hear it. That teachability—its deceptive simplicity—doesn’t reduce the song; it proves the point. The song is a road that welcomes more travelers than it warns away.

“Songs like this don’t beg for attention; they wait for the hour when you’re ready to hear what they were going to say anyway.”

If you’re looking for ornate modulations or showpiece instrumental breaks, you won’t find them here. You’ll find a restraint that refuses to prettify living. The lines don’t gild heartbreak; they inventory it. The arrangement doesn’t inflate; it breathes. And Harris’s harmony doesn’t gild Kristofferson; it steadies him. That’s why the performance endures—not only as a showcase of two icons, but as a document of artistic ethics.

Context deepens the song’s resonance. The Silver Tongued Devil and I marked a moment when Kristofferson’s songwriting was reaching a wider public; in that period he was still becoming the figure he’d later be remembered as, even as his songs were already teaching listeners how to read him. Producer Fred Foster, whose role on the album is widely noted, knew how to let a lyric stand without frills, and that sensibility still shapes how “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33” is staged in later revivals. The Blackbird Presents tribute, released decades later, feels faithful to that spirit: celebrate the song by getting out of its way.

A final note about listening. This is a performance that rewards the simplest of conditions: a quiet room, an unhurried mind, and the volume just high enough that the breath before each entrance is audible. If you’re accustomed to the treadmill of a modern music streaming subscription, pause the shuffle and give this one a full pass, start to finish. Let it do its slow work. The song doesn’t solve anything. It doesn’t try to. It places a hand on your shoulder and names the ache without judgment.

And when it ends, there’s a little hush that feels like a choice. Not silence—space. In that space you can inventory your own contradictions, your own pilgrim’s debt, and decide what kind of truth-telling you’re willing to carry forward. That’s the real afterglow of “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33.” Not the applause, not the neat cadence, but the way it persuades you to listen harder to your own life.

If you’ve only ever filed Kristofferson under the banner of country legend, take this as an invitation to hear him anew. Go back to the 1971 album cut for the origin story, then let the Harris duet redraw the lines with the knowledge of years. You’ll find the same skeleton in both versions—a moral x-ray of the artist’s vocation—articulated with slightly different light.

And that, I think, is why we keep returning to this song. It’s not nostalgia. It’s recognition. In the pilgrim, we see the learner and the striver, the lover and the liar, the one who keeps walking because the road is the truest story he can tell.