I first heard “La-La (Means I Love You)” the way it should be heard: drifting from a small radio after midnight, when the room is dark enough for strings to glow. The volume was low, the world quieter than usual, and the opening figure—those soft, bell-like accents and murmuring rhythm—felt like someone exhaling right beside me. The record doesn’t arrive; it appears, the way a memory reenters a room.

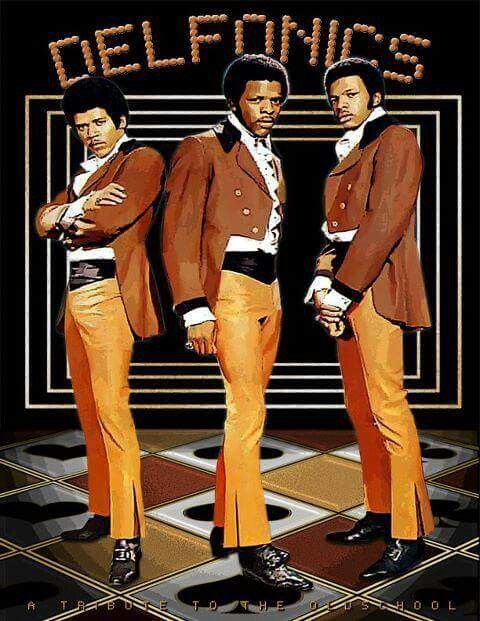

In 1968, The Delfonics released this single on the Philly Groove label, and it quickly established them as architects of a new softness in soul. The song would soon be collected on their debut album of the same name, a marker in their career that coincided with producer-arranger Thom Bell refining a language of orchestral R&B that Philadelphia would export to the world. You can hear Bell’s hand in the disciplined elegance and in the way each texture enters with purpose.

What makes “La-La (Means I Love You)” so disarming is its poise. William Hart sings as if handling a fragile glass, each syllable floated, never forced. Beneath him, the arrangement keeps a measured heartbeat: gentle bass, brushed drums, and a rhythm section that treats space like an instrument. There’s no hurry, no excessive flourish, just an unfolding.

The timbral palette is precise. High strings carry the melodic crown, sustained long enough for the reverb to feather at the edges. A celeste or glockenspiel-like color punctuates phrases with a shimmer, almost like light reflecting off water. Woodwinds glide in supportive arcs rather than stealing focus, and the horns, when they appear, behave like polite guests.

Listen closely to the center image. The lead vocal is close-miked enough that you catch the breath onset before certain phrases, and yet it never feels naked. Background voices arrive as velvet underlay, doubling or echoing fragments without clutter. Bell sets the falsetto in a cradle of air.

There’s guitar in there, but it’s a lesson in restraint—clean, undistorted, tending toward hushed arpeggios and little linking figures between phrases. You might miss it the first few plays because it refuses to announce itself; it functions like stitching, the thing that binds, yet hides. The piano adds harmonic ballast in the midrange, padding the chord changes with soft triads and the occasional suspended tone that resolves with a sigh.

On studio headphones, the song reveals its small miracles. A faint tape hiss sits like a veil you forget exists. Plate-style reverb tails shimmer but stop before sentiment turns syrupy. The drums never punch; they articulate, their transients rounded, their decay just long enough to preserve the lullaby energy. It is a piece of music designed to bloom at low volume.

Historically, the single mattered. It charted high on both the pop and R&B lists, the kind of crossover success that told radio programmers the public had an appetite for tenderness. Within the Delfonics’ trajectory, it was a statement: these singers from Philadelphia could make a whisper carry further than a shout. In that whisper, you can hear the roots of what would later blossom into the broader Philadelphia International sound of the early ’70s.

The arrangement’s genius lies in how it makes simplicity feel opulent. Take the chorus construction. The most childlike syllables—the “la-la”—become the emotional hinge, but Bell refuses to overload it. He lets repetition work. Strings unfurl a gentle counter-line; the rhythm section steps half a foot forward; background voices lift like a curtain rising just enough. It’s patient, nearly ceremonial.

There’s also the way it stages intimacy. The lead vocal almost never breaks a sweat. William Hart’s falsetto doesn’t plead; it offers. That choice changes the ethics of the love song. Instead of conquest or performance, we get an invitation to quiet. The Delfonics learned that carving away is a kind of courage.

I like to imagine the first time a listener in 1968 dropped the needle on a fresh 45 of this single. The room would tilt toward that glinting upper-register percussion, that polite rhythm guitar, and they’d realize they were being asked to meet the music halfway. Not to be dazzled, but to be welcomed.

“Beauty here isn’t loud—it’s carefully placed, like a handwritten note slipped under a door.”

In production terms, the record exemplifies balance. Strings never swamp the midrange; the voices retain a luminous forwardness; low-end warmth is present but refuses to boom. The mix chooses clarity over spectacle. You can imagine Bell at the console, favoring decisions that make the vocal feel like the sun and everything else like air.

If you compare this to contemporaneous Motown ballads, you feel the contrast between Detroit’s brighter, more percussive punch and Philadelphia’s satin edges. This isn’t to say one is better, only that the Delfonics brew a lighter gravitas. It’s the difference between a spotlight and candlelight.

The lyric conceit is audaciously simple. How many times can you say “I love you” without saying it the same way twice? The Delfonics turn the question into craft. The syllables are affectionate, almost playful, yet the arrangement keeps the song from floating away. Romance, here, is anchored by design.

Thom Bell’s career would soon include landmark collaborations—The Stylistics, later work that helped define the city’s romantic string writing—but “La-La (Means I Love You)” is an early signature. It sketches the grammar: softened rhythm, orchestral texture, falsetto leadership, an almost courtly pace. You can feel the blueprint for a decade of soft-soul devotionals.

One of the pleasures of this recording is how it lives differently on different systems. Through a small mono radio, it’s all glow: a merge of voice and strings into one embrace. With premium audio, you can separate the strands, track the cellos’ gentle underpinning, notice the short consonant tails on background vocals. Each pass yields another thread.

Three small vignettes come to mind, each one proof that the song still moves in the present tense.

First: a barista closes a café, the industrial hum finally clicking off. They queue a playlist of older soul and forget to skip forward when “La-La” starts. The last customer, tying a scarf, begins to hum, faintly surprised that the melody arrives already memorized. Some songs we don’t learn; we remember them returning.

Second: a newly married couple chooses it for the first slow dance at a reception under dim Edison bulbs. No show-stopping lifts, no photogenic dips. Just a sway. Guests lean into conversations. The couple seems to shrink the room, the way the song shrinks time.

Third: a teenager digging through a parent’s 45s discovers the single in a paper sleeve. They drop the needle and hear how arrangement can be affectionate. Later, they go looking for more and find that The Delfonics weren’t a one-song group. “Ready or Not Here I Come (Can’t Hide from Love)” offers a brisker tempo; “Didn’t I (Blow Your Mind This Time)” carries a matured ache. A world opens.

For all its fragility, there’s grit at the core. The performance is controlled, but that control suggests discipline earned rather than a lack of feeling. You can sense studio hours, arrangement drafts, and a team whose standard was elegance without excess. The record is curated sweetness.

If we zero in on the rhythm section, the drummer favors tip-of-stick lightness on the ride, soft snare articulations, and kick patterns that keep pulse rather than pressure. The bass lines move in stepwise motion, often outlining chord roots and fifths before slipping into a quick passing tone. Nothing risks dislodging the vocal.

The backing vocals, meanwhile, act like a spell. They repeat, echo, and in some moments behave like a second lead, but they always step back just in time. Their blend is airy but together, the kind of ensemble cohesion that tells you these singers have been standing in a line for a long time, listening to breath.

One could call this orchestral R&B, but that undersells the craftsmanship. The orchestration is not an adornment; it’s the emotional setting. Without those high strings singing in parallel thirds and those bell-tones flickering at the top, the song’s thesis would feel less inevitable. The arrangement is the love letter’s paper, not just the ribbon.

As for the broader context, “La-La (Means I Love You)” arrived at a moment when popular music’s grand gestures were getting louder. Psychedelia, harder rock, increasingly political soul—every corner of the late ’60s thrilled to announce itself. The Delfonics did something subversive by going the other direction. They made quiet the headline.

Because the single sits on the cusp of what we now call Philly soul, it anticipates the smoother ’70s. You can draw a dotted line from this to The Stylistics’ early-’70s hits, to those records where strings are not a luxury but a grammar. The Delfonics helped write that grammar, and the city kept speaking it for years.

The song’s endurance might also be practical. It lives happily at weddings, on late-night radio, in curated playlists, even in solitary headphones on a subway. Its tempo is forgiving; its melody invites casual harmony; its sentiment avoids the smothering edge of some ballads. It’s inclusive romance.

If you’re listening today, do one intentional pass. Sit, reduce distractions, and let the first minute do its work. Notice how the arrangement holds back, how the chorus doesn’t try to outshout the verse, how the bridge—brief, necessary—refreshes the chord colors without drama. You will hear economy functioning as generosity.

That’s the paradox at the heart of The Delfonics. Glamour and grit cohabit. The glamour is the tuxedo sheen of strings and falsetto purity; the grit is the studio discipline, the choice not to overreach, the humility of players who make space. Simplicity is the show.

If you haven’t yet, trace the group’s arc around this period. The single’s success—high on pop and R&B charts—gave The Delfonics room to aim further, and you can hear the confidence in the follow-ups. Thom Bell, working alongside label figure Stan Watson, would become even more central to the city’s sonic identity, but the essential insight is already here: gentleness travels.

In the end, I think of “La-La (Means I Love You)” as an object lesson in what tenderness can accomplish in three minutes. It doesn’t innovate via complexity; it refines via care. A listener today, even on a busy commute, can enter its climate within five seconds. Some climates are better than destinations.

For anyone who collects these eras, the single’s sequencing on the debut album matters because it frames the group’s promise. It says: we can do lightness without fluff, sentiment without sap, orchestration without overstatement. That’s a rare pledge, and rarer still to keep.

If the record has a moral, it’s that restraint, when combined with craft, makes emotion durable. We return to it not to be astonished, but to be steadied. Songs that steady us become part of our furniture, the good kind, the kind that ages with us.

Before I close, a listening tip. Stream the track once casually, and then again with good isolation. You’ll catch tiny consonant clicks and how the strings hand off a phrase to the winds like two dancers passing a ribbon. Those details aren’t decoration; they’re architecture.

And when the last chorus rounds the bend, you realize the song has taught you a way to speak: fewer words, better placed. In a noisy world, that is radical.

As the fade arrives, it doesn’t feel like an ending. It feels like a promise to reappear whenever kindness is needed.

If you cue it up tonight, give the room to it. It will repay the favor.

—

Listening Recommendations

The Stylistics – Betcha by Golly, Wow

Thom Bell’s orchestral touch and Russell Thompkins Jr.’s airy lead make this a sister text in Philadelphia romance.

The Moments – Love on a Two-Way Street

A slow-burn sweet-soul ballad with delicate strings and a wistful melody that moves in the same tender lane.

The Jackson 5 – I’ll Be There

Gentle, string-lit devotion with youthful sincerity; a masterclass in understatement from the Motown camp.

The Chi-Lites – Oh Girl

Soft-spoken soul with elegant arrangement and an unforgettable harmonica thread, balancing restraint and ache.

Blue Magic – Sideshow

Another Philly-bred heartbreaker where orchestration carries the emotion with theatrical grace and soft focus.