The year is 1958. Rock and roll is a raw, electric scream still finding its footing, and the American airwaves are dominated by the primal energy of Elvis and the swagger of Chuck Berry. Across the Atlantic, in a pre-Beatles, grey London, something entirely different—and utterly unexpected—was happening. It was the moment a 13-year-old schoolboy named Laurie London stepped into the spotlight and, with a voice that was both innocent and strangely powerful, transformed an American spiritual into an unlikely global smash.

I often think about this record when I’m scrolling through a music streaming subscription service, seeing the endless, hyper-curated playlists of today. It reminds me of an era when a simple, sincere performance, plucked from obscurity, could genuinely stop the world. London’s rendition of “He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands” is not just a forgotten hit; it’s a cultural anomaly, a moment of pure, innocent sincerity cutting through the early grit of rock’s revolution.

The Context of the Schoolboy King

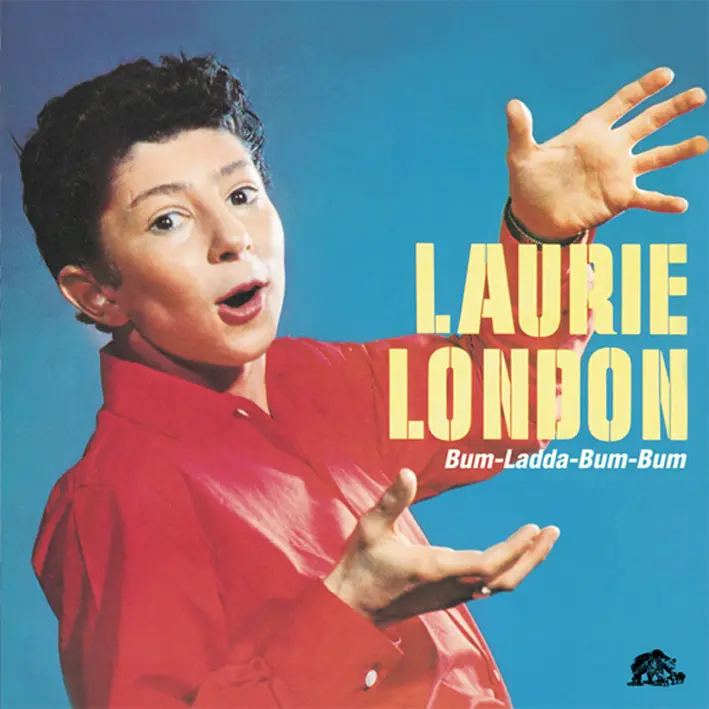

Lawrence ‘Laurie’ London was born in East London in 1944. His ascent was meteoric, a true “right place, right time” story of the late Fifties. Reportedly discovered after an impromptu performance at a BBC radio show event, he was quickly signed to Parlophone Records. His career arc essentially begins and peaks with this one single, a non-album track that would define his brief, spectacular moment of fame.

He recorded the song in 1957, with the release hitting the U.K. charts late that year before exploding in the United States in the spring of 1958. It was a staggering success: a gold record, and a bona fide No. 1 hit on Billboard’s “Most Played by Jockeys” chart—an astonishing achievement for a British male singer in the pre-Invasion era. The song was credited to British writers using pseudonyms, having been adapted for a stage musical, yet its spiritual heart was undeniable. London was working with producer Norman Newell, an EMI veteran, at Abbey Road Studios, placing this small, profound recording right at the epicenter of British recording history.

It’s crucial to understand what this piece of music fundamentally is: an African-American spiritual, born of oral tradition, expressing faith and resilience. To hear it sung by a Jewish schoolboy from London’s East End, backed by a lavish orchestral arrangement, highlights the strange, beautiful way music travels and transforms.

The Sound of Sincerity: Voice and Arrangement

The power of this record lies in the breathtaking contrast between its components. At the center is Laurie London’s voice—a boy treble, clear as a bell, with a vibrato that suggests a talent far beyond his years. The performance is delivered with astonishing earnestness, devoid of the forced theatricality one might expect from a child star. His phrasing is direct, letting the words carry the weight.

This youthful purity is set against the polished, professional backdrop of the Geoff Love Orchestra. This is not a stripped-down skiffle track; it is grand, mid-century pop orchestration. The sound is full, captured with a clarity that speaks to the quality of Abbey Road’s engineering, even in the late Fifties. A tight, yet lush, string section provides a sweeping, almost cinematic backdrop.

The rhythm section is crisp and propulsive, a moderate, swinging tempo that turns the gospel call-and-response structure into a jaunty pop number. We hear an active bass line walking beneath the melody. Though dominated by the orchestra, the arrangement includes a discreet, rolling piano accompaniment, providing harmonic colour and drive beneath the strings. There’s no prominent guitar solo or riff; the focus is entirely on the choral-orchestral swell and the voice that cuts through it all.

The overall sonic texture is bright and highly compressed—perfect for the AM radio bandwidth of the time. The dynamics are well-controlled, swelling gently on the chorus as a mixed choir (the Rita Williams Singers reportedly contributed) reinforces the central message, then pulling back for London’s solo delivery of the next line, “He’s got the whole world in His hands.”

“The magic of Laurie London’s recording is that it is simultaneously a genuine gospel expression and a perfect piece of innocent, Fifties pop, a sacred text given a secular polish.”

A Micro-Story of Global Reach

Imagine the scene: America in 1958. A young couple in a diner, dipping fries in ketchup, listening to the jukebox. The record drops. They hear a song about cosmic certainty, sung not by a seasoned gospel shouter from the South, but by a 13-year-old British voice that sounded like hope itself. This emotional dissonance—the old, deep spiritual message delivered by this new, young vessel—was what gave the song its improbable lift.

For a generation just starting to worry about the Cold War, the song was an unexpected balm. It wasn’t on an album; it was simply there, on the radio, an omnipresent cultural artifact that transcended genre lines, appealing to rock-and-roll teenagers, their parents, and Sunday morning listeners alike. This single was arguably one of the first truly global pop records to succeed primarily on the strength of its heartfelt delivery and universal message, rather than its genre novelty.

This universality explains the song’s legacy, which extends well beyond London’s own short career. After this enormous hit, London, facing the demands of fame as an adolescent, stepped away from music around age 19, never to match that initial chart success in the UK or USA, despite later recordings, including some in German. The boy wonder simply vanished from the major charts as quickly as he arrived.

Yet, every time the song resurfaces—in a movie, a commercial, or on a deep-cut radio slot—it carries that initial, earnest impact. It’s a testament to the power of a single moment of perfect casting and arrangement. The arrangement of the original, with its simple, block chords, has inspired countless sheet music arrangements for choirs and schools over the decades, a musical blueprint for hope.

The enduring success of this particular recording lies in its unshakeable, gentle certainty. It never tries to be cool, never attempts to be edgy. It simply delivers a message of profound comfort with crystal clarity, capturing a moment just before the British Invasion changed everything, yet hinting at the global reach that British artists would soon command. It remains a fascinating listen, a quiet pillar in the architecture of pre-Beatles transatlantic pop.

Listening Recommendations: Songs of Innocence, Orchestration, and Crossover

- The Chordettes – “Mr. Sandman” (1954): Features similarly innocent vocal delivery and high-production choral harmony that defined late-Fifties pop.

- Paul & Paula – “Hey Paula” (1963): Captures the same spirit of earnest, sweet-toned simplicity and clean, wholesome melody.

- Lonnie Donegan – “Does Your Chewing Gum Lose Its Flavour (On the Bedpost Overnight?)” (1959): A British male singer finding US success by transforming an American folk/novelty song, much like London exported a spiritual.

- Sam Cooke – “You Send Me” (1957): A pivotal crossover of a gospel-rooted voice into the pop charts, echoing the spiritual origins of London’s hit.

- Johnny Preston – “Running Bear” (1959): Another contemporary chart-topper using a narrative approach and a strong, distinctive vocal performance with a big orchestral sound.

- The Springfields – “Island of Dreams” (1962): Displays the polished, sophisticated British pop sound and orchestral backing that was refined in the period between London’s hit and the onset of the Merseybeat era.