The dial glows softly in the pre-dawn kitchen, spitting static between the big city radio stations. It’s 1965, and the airwaves are a beautiful, brutal battlefield. British Invasion bands are still landing salvos, but something else is emerging from America’s urban centers—a sound slicker, more ambitious, and built on a furious rhythm section. This is the moment Len Barry, a veteran of the Philadelphia vocal scene, steps into the light with his definitive solo statement: the magnificent two-minute-and-change explosion known as “1-2-3.”

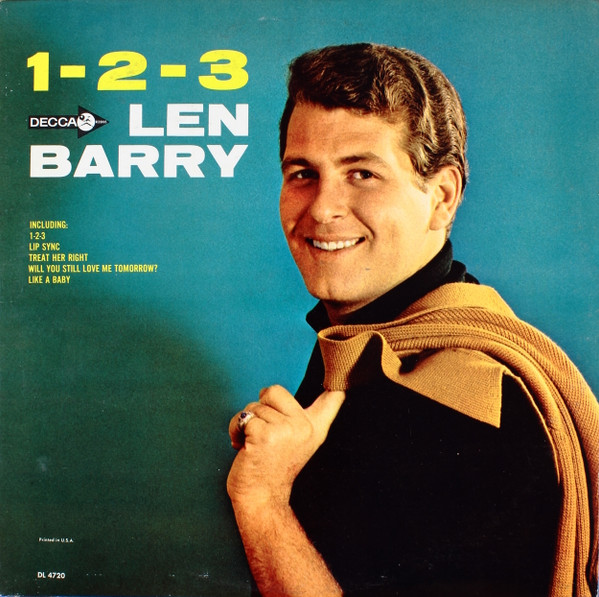

Hearing that opening drum fill—crisp, insistent, and slightly echoing—you can almost smell the polished wood and damp plaster of a classic East Coast studio. It’s an immediate promise of kinetic energy. The song is a marvel of compression, a dizzying blend of garage-rock propulsion and big-band polish. It arrived on Decca Records in the U.S. and was later the title track of his 1965 debut solo album for the label.

Before this hit, Barry, born Leonard Borisoff, was known for his work with the Dovells, the doo-wop group famous for “Bristol Stomp.” His solo shift into blue-eyed soul was not a gradual pivot but a decisive leap. “1-2-3” positioned him, however briefly, alongside giants who fused R&B grit with pop accessibility. The song’s success was formidable, soaring high on both the U.S. and U.K. charts.

The Philadelphia Blueprint

The engine room of “1-2-3” is pure, unadulterated Philadelphia muscle. The song was co-written by Barry himself, alongside John Madara and David White, the latter two of whom also took on the production duties as Madara-White Productions. Their vision was clear: to take the infectious simplicity of pop and elevate it with a sophisticated, soulful arrangement.

The arrangement, credited to the brilliant Jimmy Wisner, is what elevates this simple pop tune into a lasting piece of music. The track doesn’t just feature a rhythm section; it showcases a miniature orchestra operating at maximum velocity. The bass, reportedly played by Joe Macho, establishes a powerful, forward-lurching groove, laying the harmonic floor for the brass and woodwinds to dance.

The instrumentation is complex for a two-and-a-half-minute single. A tight, driving drum part, courtesy of Bobby Gregg, anchors the whole track. Then the melody arrives, carried by Len Barry’s clear, agile voice. His vocal performance is remarkable for its breathless urgency, balancing the soul sensibility he inherited with a clean, radio-friendly attack.

Listen closely to the backing track. There’s a relentless, high-energy counterpoint. The electric guitar work is understated but essential, offering sharp, syncopated jabs rather than a sweeping melody. It locks in tightly with the bass, creating that insistent, almost nervous rhythm that propels Barry’s rapid-fire delivery.

Crucially, the horns are not a mere accent. They are woven directly into the rhythmic structure. The track features a formidable brass contingent, reportedly including Lee Morgan on trumpet and both Bill Tole and Roswell Rudd on trombones. Their stabs and swells, sharp as a switchblade, give the song its undeniable kinetic energy. This is a sound engineered for dance.

The Piano, the Pulse, and the Controversy

The true depth of the arrangement appears in the detail. Listen for the percussive role of the piano, played by a young Leon Huff, a name that would soon become synonymous with Philadelphia International Records. It provides a bright, rhythmic sparkle, bubbling beneath the surface tension of the horns and drums. Huff’s contribution here is a fascinating piece of pre-Philly Soul history, showcasing the rhythmic sophistication that would define the genre a decade later. This early collaboration underlines how crucial the city’s session players were to the development of popular music in the mid-60s.

The complexity of this recording is astonishing, a testament to the session players’ skill. This wasn’t a cheap pop record; it was a dense, meticulously layered production designed to fill the vast dynamic range of premium audio equipment. The sheer density of sound—drums, bass, multiple guitars, saxophone, clarinet, trumpet, and trombones—all coalesce without muddying the mix.

“The magic of this song lies in its ability to marry the simple, declarative joy of a schoolyard chant with the full, roaring sophistication of a big-city horn section.”

The song’s simplicity, however, masked a period of significant legal friction. The writers were famously sued by Motown. The claim alleged that “1-2-3” was essentially a re-tooling of the Holland-Dozier-Holland composition “Ask Any Girl,” a Supremes B-side. After lengthy litigation, the parties settled, and Madara, White, and Barry agreed to list the Motown writers as co-authors, cementing the song’s place in a complicated lineage of mid-60s soul. This controversy is a reminder that in 1965, the line between musical inspiration and outright replication was a frequent battleground for pop supremacy.

A Cinematic Sense of Urgency

The emotional landscape of “1-2-3” is pure, immediate infatuation. Barry delivers the lyrics—the simplest, clearest metaphors for falling in love—with an earnest, slightly strained urgency that is utterly compelling. “One, two, three, oh, that’s how elementary it’s gonna be,” he sings, his voice cutting through the brass fanfare. This vocal performance is the center of the storm, conveying a rush of emotion that is almost physical.

Think about the structure. It’s tight, compact, and never lets up. There’s no fade-in, just a sharp, rhythmic declaration that grabs the listener by the collar. This structural efficiency is part of its genius. There is nothing extraneous; every instrumental line serves the purpose of forward momentum.

I often imagine this piece of music playing during a crucial montage in a classic 1960s film. The scene cuts rapidly—a first kiss, a rush through a downtown street, the moment a young couple decides to run away together. The song is a soundtrack for the instant decision, for the moment when complexity is brushed aside by clear, simple emotion. It’s why the track has endured far beyond its original chart run. Decades later, its vibrant energy is undiminished, a perfectly preserved capsule of mid-sixties pop-soul exuberance.

The Long Echo

Today, when we stream this classic, we are listening not just to a hit single, but to a precursor. The studio techniques and the use of the rhythm section alongside sweeping, jazz-inflected horns set a clear precedent. This production style foreshadows the orchestral sophistication that would soon characterize the nascent “Philly Sound” of the early 1970s. Madara, White, and Wisner crafted a sound that was too rich for simple classification. It was pop built on soul foundations.

For the modern listener, “1-2-3” is a masterclass in musical economy. It proves that maximalist instrumentation can exist within a minimalist runtime. The song is a burst of concentrated joy, perfectly distilled, and one that should be required listening for anyone exploring the origins of sophisticated American pop music. It’s also a perfect track to revisit—a simple lesson in love, learned quickly, and never forgotten.

The energy of this song makes me think of high school dances in gymnasiums, the polished floor reflecting the ceiling lights, the air thick with youth and promise. The song is an anchor to that feeling of simple, overwhelming clarity. One, two, three. That’s all it took. That’s all it ever needs.

Listening Recommendations

- The Tams – “What Kind of Fool (Do You Think I Am)” (1964): Features a similar driving, up-tempo rhythm and a full, joyful orchestral arrangement that defines the era.

- The Four Seasons – “Working My Way Back to You” (1966): Shares the dramatic vocal urgency and a pop structure propelled by a powerful, multi-layered rhythm section.

- The Young Rascals – “Good Lovin'” (1966): Captures the same energetic, raw, blue-eyed soul vocal performance over a relentless, infectious beat.

- Roy Head – “Treat Her Right” (1965): Another blue-eyed soul staple from the same year, blending R&B vocals with a high-octane, brass-heavy groove.

- Doris Troy – “Just One Look” (1963): Pre-dates “1-2-3” but offers the same feeling of immediate, giddy infatuation delivered with a powerful, soul-infused vocal.

- Jay and the Techniques – “Keep the Ball Rollin'” (1968): A later example of horns and harmony vocals fused to a snappy, Motown-influenced pop-soul rhythm.