There are songs that arrive like a thunderclap—demanding attention, swelling with chorus and confidence. And then there are songs like “Silver Blue.” Songs that do not storm the room but linger in it. Songs that feel less like a performance and more like a confession spoken softly after midnight.

On September 15, 1975, Linda Ronstadt released Prisoner in Disguise through Asylum Records. The album would climb to No. 4 on the Billboard 200, confirming that Ronstadt was no longer simply admired—she was ascendant. Her voice was becoming one of the defining sounds of the decade. Yet tucked at the very end of that platinum-reaching record was something far more intimate than chart positions: a closing track called “Silver Blue.”

It did not chase radio. It did not explode with hooks. Instead, it closed the album the way twilight closes a day—slowly, deliberately, beautifully.

The Album That Framed the Silence

Prisoner in Disguise was recorded at The Sound Factory in Los Angeles between February and June 1975, under the careful production of Peter Asher. By that point, Ronstadt had mastered the art of inhabiting other writers’ songs. Throughout the album, she moved confidently through material by Neil Young, Lowell George, and Smokey Robinson—artists whose emotional worlds were distinct, yet somehow expanded inside her voice.

But if the album begins with breadth, it ends with focus.

“Silver Blue” narrows the emotional lens. It does not perform heartbreak theatrically. It observes it. It understands it. And in that understanding lies its quiet power.

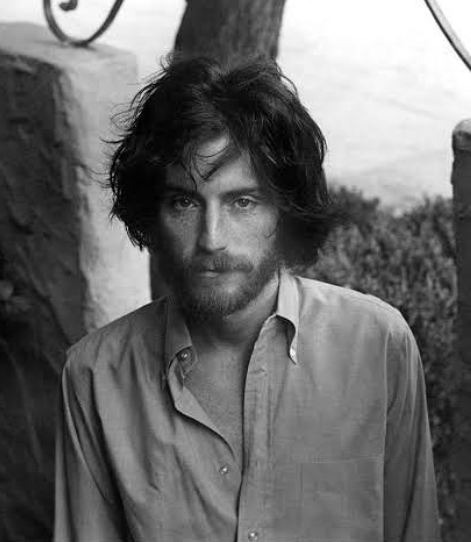

J.D. Souther: Writing Loneliness in California Light

The song was written by J.D. Souther—one of the most quietly influential architects of the Southern California sound. Souther’s songwriting carried a particular tension: sunlit melodies shadowed by emotional solitude. He understood something essential about 1970s Los Angeles—the glamour and the loneliness were often inseparable.

On “Silver Blue,” Souther does more than write the words. He contributes harmony vocals and plays acoustic guitar on sessions connected to the track. That detail matters. It adds an almost cinematic dimension: the songwriter standing close by while Ronstadt interprets the ache he placed on the page.

There is something profoundly fitting about that collaboration. Souther provides the emotional blueprint; Ronstadt builds the cathedral.

The Color of Heartbreak

The title itself feels like emotional weather.

Silver: reflective, cool, distant light.

Blue: the ache that needs no translation.

Together, “Silver Blue” suggests a love that has passed through fire and settled into memory—not erased, not destroyed, but transformed. This is not the heartbreak that slams doors. This is the heartbreak that has already accepted what cannot be undone.

Ronstadt sings as though she’s standing on the far side of a storm. The sky has cleared, but the pavement is still wet. Her voice carries restraint—not because the pain is small, but because it has matured. She doesn’t oversell the sorrow. She honors it.

And that restraint is precisely what makes the performance devastating.

The Flip Side of Fame

In 1975, Ronstadt released “Love Is a Rose” as a single. It debuted at No. 73 on the Billboard Hot 100 and eventually peaked at No. 63—a modest but respectable chart showing. On the reverse side of that vinyl single sat “Silver Blue.”

The symbolism is impossible to ignore.

A-side: the song positioned for airplay.

B-side: the song waiting quietly for discovery.

“Silver Blue” belonged to that second space. It was never designed to roar through transistor radios. It was built for headphones, for late drives, for listeners who flipped the record and kept listening after the applause had faded.

And sometimes, those are the songs that endure the longest.

A Closing Track That Feels Like an Epilogue

Album sequencing is an art form, and placing “Silver Blue” as the final track transforms its meaning. Throughout Prisoner in Disguise, Ronstadt proves her vocal authority—moving through rock, country, and pop with effortless control.

But at the end, she chooses softness.

The album does not conclude with triumph or collapse. It concludes with acceptance. “Silver Blue” feels less like a finale and more like an emotional epilogue. It does not declare that love won or failed. It suggests something more nuanced:

Love happened.

And now we live with what remains.

That idea is universal. Relationships do not always leave in flames. Sometimes they leave in color—in subtle shifts of how we see the world. “Silver Blue” captures that shift.

Ronstadt’s Voice: Strength in Stillness

One of the most remarkable qualities of Linda Ronstadt’s 1970s work is her control. She possessed the power to belt with operatic force, but she also understood when to pull back. On “Silver Blue,” she sings with the kind of steadiness that suggests lived experience rather than theatrical drama.

There is no vocal acrobatics for applause. No crescendo engineered for radio drama. Instead, her delivery feels measured, almost conversational—yet luminous.

The performance reflects a deeper truth: some heartbreaks do not require volume to be heard.

Her phrasing lingers just slightly behind the beat, as if she is considering each word before letting it go. That subtle delay adds to the sense of reflection. It feels less like she is reliving the pain and more like she is remembering it.

Memory, after all, is often silvered by time.

Why “Silver Blue” Still Matters

Nearly five decades later, “Silver Blue” retains a secretive aura. It has never been among Ronstadt’s most shouted-about hits. It does not dominate greatest-hits compilations or soundtrack playlists.

But it endures.

It endures because it speaks to the quieter truths of adulthood—the realization that not all love stories end in spectacle. Some end in understanding. Some end in a soft recalibration of who we are.

In a music industry that often rewards intensity and immediacy, “Silver Blue” offers patience. It invites the listener to sit with the feeling rather than outrun it.

And perhaps that is why it resonates across generations.

The Legacy of a Quiet Goodbye

There is a particular kind of courage required to close an album this way. After proving commercial dominance and vocal mastery, Ronstadt chooses understatement. She chooses a song that whispers rather than shouts.

That decision says something about her artistry.

It suggests she understood that legacy is not built only on high notes and chart peaks. It is built on moments of honesty. On songs that stay with listeners long after the radio moves on.

“Silver Blue” does not demand to be everyone’s favorite. It asks only to be someone’s.

And for those who understand its language—the language of reflective sorrow, of mature acceptance, of love remembered without bitterness—it becomes unforgettable.

A Song That Glows Instead of Burns

If you only know Linda Ronstadt from her towering choruses and bold radio hits, “Silver Blue” will surprise you. It reveals a different dimension—one that is softer, yes, but no less powerful.

It is the sound of a candle being set down carefully after the room has emptied.

It is the moment when applause fades and memory remains.

It is heartbreak not as spectacle, but as color.

Silver.

Blue.

And forever luminous.