When Heartbreak Became a Declaration of Power

In the autumn glow of early 1970s American television, something electric flickered across the screen. It wasn’t pyrotechnics or spectacle. It was a voice — clear, commanding, and emotionally unflinching. When Linda Ronstadt stepped onto the stage of The Midnight Special in 1973 to perform “You’re No Good,” she wasn’t yet the chart-dominating force she would soon become. But in that moment, she was already transforming.

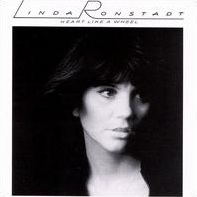

The studio recording of “You’re No Good” would climb to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1975, anchoring her landmark album Heart Like a Wheel and cementing her as one of the defining voices of the decade. Yet long before radio saturation and platinum accolades, there was this performance — raw, immediate, and utterly magnetic. It captured Ronstadt in transition: shedding the last traces of her folk-rock beginnings and stepping boldly into a fuller, roots-infused sound that fused rock, country, and soul into something uniquely her own.

A Song Reborn in a New Voice

“You’re No Good” was not originally Ronstadt’s song. Written by songwriter Clint Ballard Jr., it had been recorded by several artists during the 1960s. Most notably, Betty Everett delivered a soulful R&B rendition in 1963 that carried the sting of betrayal in a smooth, groove-driven arrangement.

But songs, like people, evolve. And in Ronstadt’s hands, “You’re No Good” became something different — less a lament and more a reckoning.

Her interpretation stripped away any lingering fragility. Where earlier versions suggested wounded affection, Ronstadt’s voice introduced steel. The famous refrain — “You’re no good, you’re no good, you’re no good / Baby, you’re no good” — was no longer a complaint. It was a verdict.

That distinction mattered.

The Threshold of Transformation

By 1973, Ronstadt had already spent years navigating the shifting currents of American popular music. From her early days with the Stone Poneys to her solo folk-rock efforts, she had demonstrated versatility, but commercial superstardom remained just out of reach. The early ’70s music landscape was changing: the California sound was blooming, country-rock was gaining legitimacy, and female performers were carving out new artistic authority.

On The Midnight Special, Ronstadt stood at that cultural crossroads.

Her live performance radiated confidence — not flashy, but grounded. Backed by tight, disciplined musicians who would soon form the backbone of her touring ensemble, she embraced a sound that balanced grit with polish. Crisp guitar lines locked into steady percussion. The groove was muscular without being heavy. It breathed.

And at the center of it all was that voice.

Ronstadt’s vocal approach in this performance is a masterclass in controlled intensity. She begins almost conversationally, allowing the melody to unfold with measured restraint. Then, as the chorus approaches, something shifts. The tone sharpens. The phrasing stretches. By the final repetition, her delivery becomes cathartic — not chaotic, but liberated.

It’s the sound of someone closing a door.

Vulnerability Without Submission

The genius of Ronstadt’s interpretation lies in its paradox. “You’re No Good” is, on the surface, a breakup song. But in her rendering, it feels less like heartbreak and more like emancipation.

In the early 1970s, female voices in rock were still negotiating space in a male-dominated industry. Emotional expression from women was often framed through vulnerability or romantic longing. Ronstadt disrupted that narrative. She didn’t plead. She didn’t collapse. She declared.

Her phrasing carries emotional intelligence — that rare ability to communicate both hurt and self-possession simultaneously. You hear the ache in the verses, but you also hear clarity. She’s not denying the pain. She’s transcending it.

That subtle recalibration transformed the song into an anthem of self-recognition. Loving badly does not mean loving weakly. Walking away is not surrender — it’s strength.

Television as Cultural Catalyst

In an era before viral clips and streaming platforms, televised performances were cultural events. The Midnight Special served as a vital stage for artists to reach national audiences in real time. Ronstadt’s appearance functioned as both introduction and declaration.

The intimacy of live television heightened the song’s emotional immediacy. There were no studio tricks to hide behind. No layered overdubs. Just band, microphone, and moment.

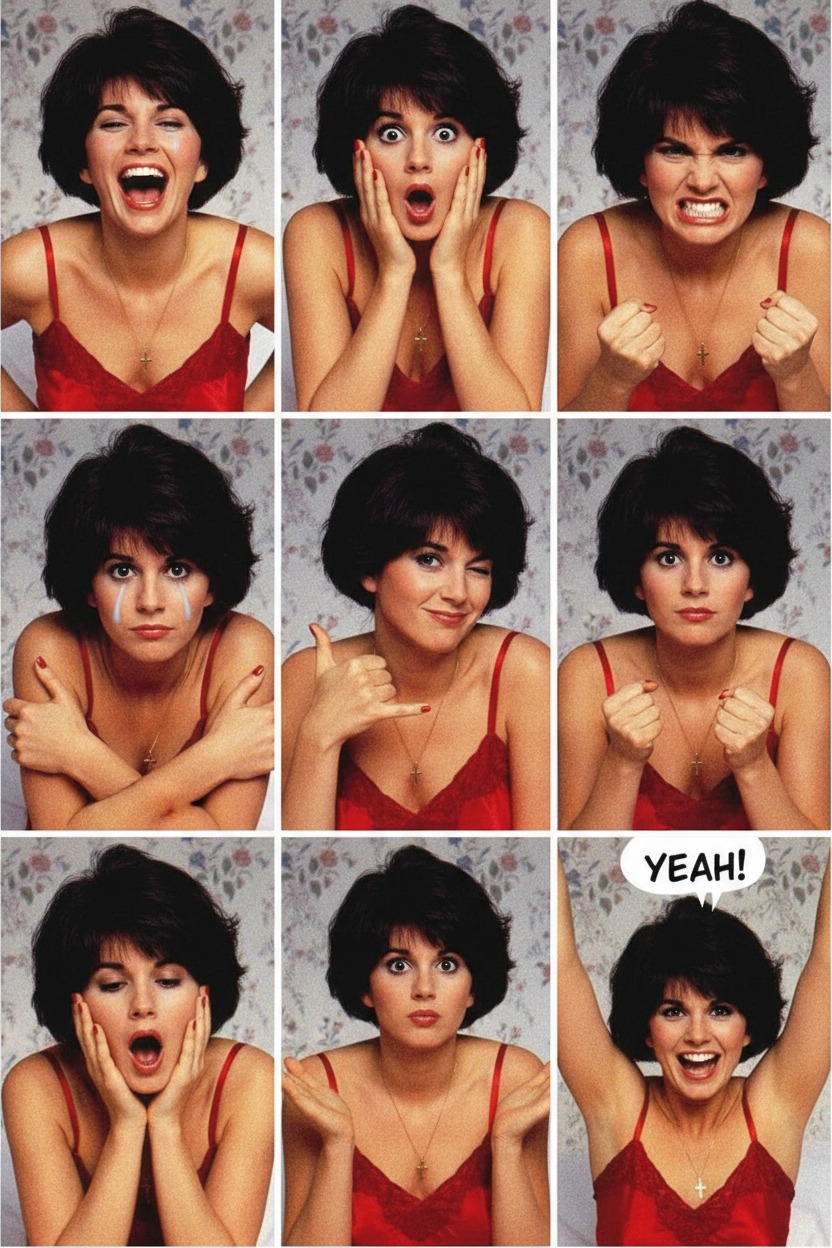

Watching the performance, one senses a quiet authority. Ronstadt doesn’t overplay the drama. She stands firm, almost statuesque at times, letting the emotional arc unfold through vocal nuance rather than theatrical gesture. That restraint amplifies the impact. When she finally unleashes the full force of her upper register, it lands like lightning.

Decades later, the footage still pulses with urgency.

From Television Stage to Chart-Topping Triumph

When the studio version of “You’re No Good” was released on Heart Like a Wheel in 1974, the groundwork had already been laid. The live performance had revealed the blueprint; the studio recording refined it. Produced with sleek precision and bolstered by impeccable musicianship, the single soared to the top of the charts in early 1975.

But even in its polished form, the essence remained the same: a balance between emotional exposure and unwavering resolve.

The album itself marked a turning point — not only for Ronstadt but for women in rock more broadly. Heart Like a Wheel demonstrated that a female artist could command commercial success while maintaining interpretive depth and stylistic authenticity. Ronstadt wasn’t just covering songs; she was inhabiting them.

And “You’re No Good” became her calling card.

The Art of Interpretation

Ronstadt’s career would later span genres — country standards, American Songbook classics, mariachi traditions — each approached with meticulous respect and emotional sincerity. Yet the seeds of that interpretive brilliance are evident in this 1973 performance.

She understood that a song’s emotional truth often lies between the lines.

The lyrics of “You’re No Good” are deceptively simple. But Ronstadt infuses them with layers: resentment tinged with lingering affection, resolve tempered by memory. It’s that dynamic tension — control versus abandon — that elevates the performance beyond nostalgia.

In many ways, this moment foreshadows the arc of her artistic identity. She would become known not merely as a singer with range, but as a singer with insight.

A Lasting Resonance

Today, revisiting “You’re No Good (Live on The Midnight Special, 1973)” feels less like archival curiosity and more like rediscovery. The performance remains startlingly modern in its emotional framing. Its message of self-worth and reclamation transcends era.

For longtime fans, it’s a reminder of the spark before the blaze. For new listeners, it’s an invitation into the genesis of a legend.

What lingers most is not the chart statistics or the accolades that followed. It’s the image of Ronstadt standing under stage lights, voice steady yet soaring, transforming a breakup song into a proclamation.

Heartbreak, in her hands, became a form of illumination.

And in that televised moment — years before streaming metrics and digital virality — a threshold was crossed. A singer became a force. A lament became liberation.

More than half a century later, the echo still rings clear:

“You’re no good.”

Not whispered in sorrow — but declared in strength.