The first time I really heard “Hurt So Bad,” it wasn’t on a crackling vinyl 45 or a classic radio dedication. It was a late, humid August night, windows down, driving through a city suddenly quiet after a thunderstorm. The static on the old AM dial shifted, and then there it was: a wall of sound, the kind that feels less like music and more like the air conditioning suddenly kicked on, blasting ice-cold sorrow directly into the car cabin.

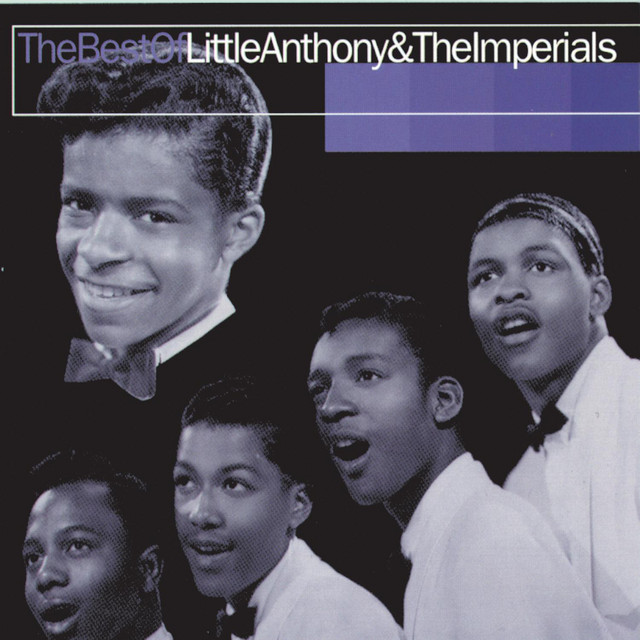

This 1965 masterpiece by Little Anthony & The Imperials is not merely a song; it’s a four-minute theatrical event. It is the sound of a world collapsing in on itself, meticulously scored. The drama is palpable from the very first breath, a quality that separates it from the more casual heartbreak of the day. It’s an elegy masquerading as a pop hit, and its enduring power lies in how it frames monumental, almost operatic grief within the tight confines of a pop single.

The Great Pivot: An Act in Three Movements

To understand the sheer magnitude of “Hurt So Bad,” we must place it precisely in the arc of the group’s career. Little Anthony & The Imperials were one of the precious few Doo-Wop era groups who managed to successfully pivot into the lush, orchestrated soul and pop sounds of the mid-sixties. After early hits like “Tears On My Pillow,” the group had a renaissance with their partnership at DCP Records, particularly with songwriter and producer Teddy Randazzo and producer Don Costa.

This new phase—often called the “Imperial” period for its grandeur—found its footing with the 1964 single “I’m On The Outside (Looking In)” and the gargantuan hit “Goin’ Out Of My Head.” “Hurt So Bad” followed, serving as the powerful second single from their pivotal 1965 album, Goin’ Out Of My Head. It was a commercial success, reaching the Pop Top 10 and landing firmly in the R&B Top Five, confirming that their move into sophisticated, high-drama soul was fully validated. They weren’t just surviving the British Invasion; they were thriving by forging a new kind of American soul ballad—one built on vulnerability, yet backed by the sonic muscle of a full orchestra.

The Anatomy of Agony: Sound and Instrumentation

The genius of this specific piece of music lies in its arrangement, a blueprint for the “uptown soul” sound that would influence countless records to follow. Teddy Randazzo, who co-wrote the track, is credited with the arrangement alongside Don Costa’s production, and together they achieved a towering, cinematic soundscape.

The opening is stark, almost confrontational: a slow, heavy pulse established by the rhythm section, where the drums are miked to capture a deep, echoing thud, less snap and more weighty impact. A simple but potent figure is played on the piano—a repeating, mournful chord progression that suggests a dark, empty room. But then the strings arrive, and the entire acoustic space changes.

These are not the polite, background strings of standard pop. They are a swirling, dramatic wash, full of thick vibrato and soaring lines that answer Little Anthony Gourdine’s lead vocal. They become a central character, illustrating the song’s titular pain with sweeping gestures and dissonant swells, especially as the song builds to its crescendo. The strings don’t just decorate the melody; they are a sonic representation of the overwhelming, almost debilitating emotion.

Gourdine’s vocal performance is, frankly, astonishing. His signature high tenor—a voice once pigeonholed as a Doo-Wop falsetto—is deployed here with a passionate control that few contemporaries could match. He sings at the precipice of desperation, never quite falling into unhinged melodrama, but instead maintaining a disciplined intensity. The vocalists of The Imperials (Clarence Collins, Ernest Wright, Sammy Strain) provide the rich, grounding vocal harmony, their presence a quiet, steadfast column of sound beneath Gourdine’s dramatic flights. They act as the internal monologue, the voice of reason or perhaps just the echo of the inevitable.

The Subtleties of the Sweep

Listen closely for the subtle textures that elevate the recording from great to transcendent. The guitar, a clean electric presence, is used sparingly. It isn’t the rock-and-roll force of the coming era; rather, it’s a delicate counterpoint, providing a quick, shimmering arpeggio or a faint, ringing strum that fills the top end of the mix just before the strings reassert themselves. This careful placement suggests restraint—a single tear, not a flood.

The dynamics are what truly sell the drama. The song is a slow, methodical climb from a whisper to a scream. It begins intimately, almost like a conversation, a quality that is only truly appreciated through premium audio equipment which can resolve the low-level detail. The intensity of the brass section, which cuts through the strings for brief, stabbing accents in the final third, is a moment of catharsis, a sonic equivalent of throwing one’s hands up in defeat.

“The song doesn’t just describe anguish; it creates a shared, high-fidelity experience of monumental heartbreak.”

Randazzo’s production philosophy for The Imperials was to treat the four men as a single, flawless instrument, capable of expressing grand emotions. They were singing stories for adults who felt heartbreak just as keenly as teenagers, but who had the experience to express it with a deeper, more sophisticated vocabulary. This is perhaps why “Hurt So Bad” continues to resonate through cover versions by artists from The Lettermen to Linda Ronstadt—the core melody and lyrical premise are robust enough to withstand drastically different interpretations, but the original’s arrangement remains the definitive dramatic statement. The song is a masterclass in how to manage sorrow, bottling the overwhelming feeling into a perfectly formed, radio-ready package.

Today, when we navigate the infinite scroll of our music streaming subscription services, we often stumble upon these relics of analog perfection. To stop and truly absorb this track is to engage with a profound form of sonic architecture. It doesn’t just describe anguish; it creates a shared, high-fidelity experience of monumental heartbreak. It is a piece of art that demands your full attention, a reminder that the most timeless stories are those of human vulnerability, dressed here in the most exquisite mid-century orchestration.

Ultimately, “Hurt So Bad” is Little Anthony & The Imperials’ triumph of texture over trend, of grand emotion over passing fad. It is the sound of a voice pushed to its limit, supported by an orchestra that understands the gravity of every syllable. It’s a song to be listened to deeply, maybe late at night, when the silence amplifies its magnificent, desolate cry.

Listening Recommendations (4–6 similar songs)

- The Righteous Brothers – “Unchained Melody” (1965): For a similar, sky-high tenor vocal paired with a soaring, full orchestral arrangement that epitomizes ‘Philly-style’ production drama.

- The Walker Brothers – “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” (1966): Shares the same sense of epic, cinematic tragedy and vocal yearning, delivered with a sweeping baroque pop production.

- Etta James – “I’d Rather Go Blind” (1967): A raw, deep-soul ballad that captures a comparable level of vocal devastation, albeit with a grittier, bluesier instrumentation.

- Doris Troy – “Just One Look” (1963): A great early example of the sophisticated uptown soul that preceded and influenced the Imperials’ mid-60s dramatic style.

- Gene Pitney – “Town Without Pity” (1961): Pitney’s emotional vocal delivery and the dramatic orchestration set a clear precedent for the highly theatrical approach heard in “Hurt So Bad.”