There is a moment in the late night, past the loud pronouncements of midnight and before the pale promise of dawn, when the radio waves feel longer, stretching across geography and time. It is in this specific stillness that certain songs, otherwise unremarkable on a sunny afternoon, gain their true gravity. Lobo’s “I’d Love You To Want Me” is one of those pieces of music—a transmission from 1972 that speaks with an enduring, velvet ache.

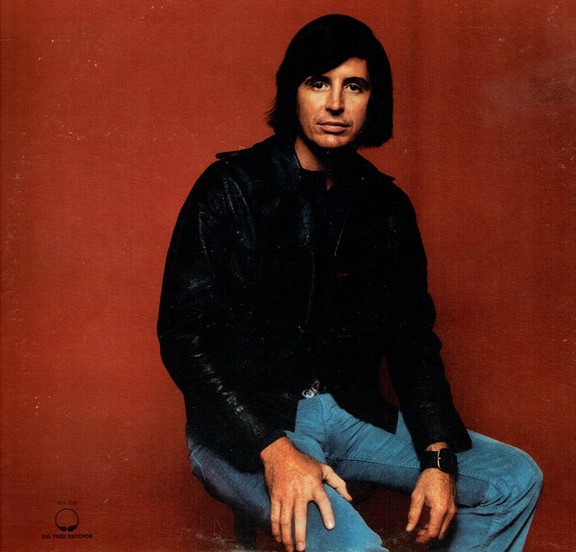

The song arrived on the American music scene riding the gentle, yet powerful, tide of soft rock. It was the second single pulled from Lobo’s sophomore album, Of a Simple Man, released on Big Tree Records. Roland Kent LaVoie, operating under the solitary pseudonym Lobo, had already made his mark with the pastoral wanderlust of “Me and You and a Dog Named Boo.” Where that earlier hit was bright and rambling, “I’d Love You To Want Me” turned inward, a study in quiet, heartfelt supplication.

The single’s success was immediate in the US, climbing to an impressive No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 and securing a No. 1 spot on the Adult Contemporary chart, a territory that would become Lobo’s domain. Globally, its reach was even more profound, topping the charts in Canada, Australia, Germany, and several other countries. This wide, transcontinental embrace speaks to the universality of its theme: the desire for reciprocation.

The track’s enduring appeal lies not in spectacular vocal acrobatics or searing solos, but in its meticulous, gentle layering. Producer Phil Gernhard understood the power of restraint. The song opens with an acoustic guitar, played with a clean, close-miked fidelity. The sound is dry and immediate, conveying a sense of intimacy—as if the performer is seated just across the room.

The foundation is built upon a subtle, almost hesitant rhythm section. The bassline moves with a melodic but unobtrusive purpose, while the drums favor soft brushes and precise, light taps on the high-hat. This creates a breathing, organic pulse that never threatens to overpower the central message. It is a clinic in the power of a soft dynamic.

🎹 Anatomy of a Whisper

The true heart of the arrangement, however, lies in the counterpoint between the rhythmic strings and the electric piano. The strings enter subtly, providing a wash of melancholy that is more texture than melody. They swell and recede, coloring the spaces between Lobo’s lines, never competing for attention.

The electric piano, likely a Fender Rhodes or Wurlitzer, provides the definitive soft rock signature. Its bell-like, slightly phase-shifted timbre fills the midrange, outlining the song’s descending chord progressions with a nostalgic warmth. It is the sound of a cool, overcast afternoon. A beginner taking piano lessons today could analyze this part to understand how to harmonize a melody with mood.

The vocal performance by Lobo himself is perhaps the most crucial element. He sings with a warm, middle-range tenor that is neither booming nor fragile. It is the voice of a man sharing a deep confession over a cup of coffee, his delivery casual yet intensely vulnerable. His phrasing is conversational, lending the slightly ambiguous lyrics—is this a breakup? a longing for a married woman? a simple, pure unrequited crush?—a weight that allows them to be personalized by every listener.

“The song is less a plea for passion and more an elegant, fully orchestrated sigh.”

Lobo’s delivery embodies the quintessential soft-rock conflict: the emotional urgency of folk music cloaked in the polished sheen of studio pop. The yearning in the lyric, “Baby, I’d love you to want me,” is delivered not as a desperate demand, but as a hopeful, almost defeated admission. It’s the kind of sentiment that hangs heavy in the air of a dimly lit bar, never quite spoken out loud.

🎧 The Cinematic Quality of Longing

The careful production ensures that even with the addition of lush strings, the mix remains uncluttered, allowing for an extraordinary sense of space. Listening to this on premium audio equipment reveals the subtle reverb tails and the nuanced blend of acoustic and electric elements that define the recording’s warmth. It is a sonic blueprint for how to elevate a folk ballad into a global pop hit without sacrificing its inherent intimacy.

Decades later, the song has transcended its era to become a quiet cultural touchstone, particularly in parts of the world where its melody and sentiment resonate deeply. It is a micro-story of romantic restraint. The listener is never told why she doesn’t want him, only that the desire for her reciprocation is an acknowledged, unavoidable fact. This lack of narrative closure is the song’s greatest strength; it allows every listener to pour their own story into its verses.

The structure of the song is deceivingly simple: verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-chorus-out. But the subtle harmonic shifts keep it from feeling repetitive. The bridge, in particular, offers a moment of emotional lift, a brief foray into a higher register that hints at the hopeful side of the longing, before settling back into the familiar, comfortable melancholia of the chorus. The acoustic guitar work provides constant, intricate accompaniment, an unassuming filigree woven through the vocal lines. It is this dedicated attention to the quiet background details that anchors the entire experience.

The enduring success of this piece of music confirms a simple truth about pop craft: sometimes, the most effective statement is the most understated. When the emotional stakes are this high, a whisper carries more weight than a scream. The arrangement allows the listener to lean in, to feel like an accidental confidante to a private, enduring heartache.

The soft-rock era, which this song helped define, was a period of emotional maturity in popular music, moving past the raw angst of its predecessors and embracing a more reflective, melodic melancholy. “I’d Love You To Want Me” stands as one of the finest documents of that time, a song that asks for nothing but gives the listener everything.

🎶 Listening Recommendations

- Bread – “Make It With You”: Shares the same gentle, acoustic-driven romantic earnestness and smooth vocal delivery from the same era.

- Seals and Crofts – “Summer Breeze”: Features a similar reliance on close-miked acoustic instruments and soft, atmospheric harmonies.

- America – “A Horse with No Name”: Exhibits the same folk-rock origins and the use of the acoustic guitar as the dominant textural element.

- Looking Glass – “Brandy (You’re a Fine Girl)”: Offers a comparable narrative focus with a slight, beautiful melancholy baked into the chord structure.

- Jim Croce – “Time in a Bottle”: Captures the same delicate, intimate singer-songwriter feel, with intricate, understated acoustic guitar work.

- Dan Fogelberg – “Longer”: A perfect example of a later soft-rock ballad that builds an overwhelming emotional resonance from a simple, gentle foundation.