I first heard “Danny’s Song” in the kind of hour you only notice when you’re awake for it: after midnight, when the lamps have been turned low and every small sound seems to carry a longer tail. The DJ barely said a word. A soft inhale, a breath on the microphone, and then that opening figure—plain, steady, unshowy—like someone pulling a chair close to tell you something they don’t want to lose to noise. There’s no grand entrance here, no dramatic curtain-pull. You come to the track the way you enter a quiet room: gently, with your hands, your ears, your guard lowered.

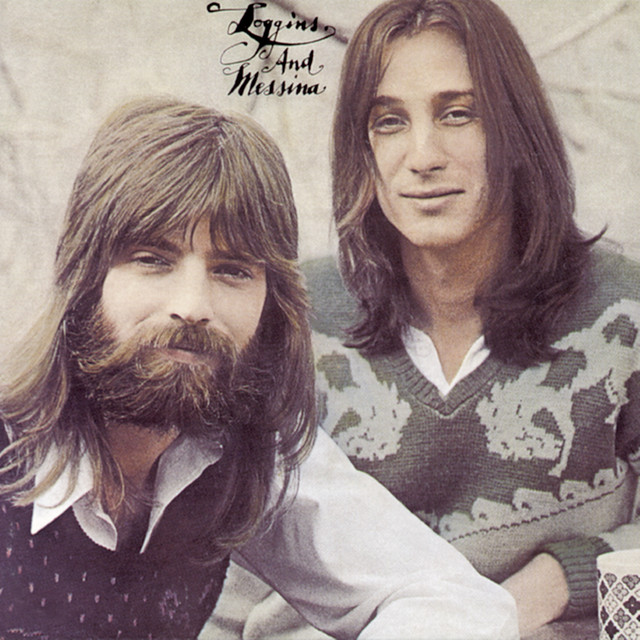

Context matters with a song this modest. “Danny’s Song” sits on Loggins & Messina’s debut set Sittin’ In, released in 1971 on Columbia and produced by Jim Messina—born of a project that famously began as a Kenny Loggins solo effort and became a duo when Messina’s musical presence proved too integral to file under “guest.” Recorded that summer at Columbia Studios in Los Angeles, the LP announces a partnership defined by pliant harmony and craft rather than flash. The tune lands early in the sequence, and it sounds like a thesis statement: here’s what we value—melody, breath, unadorned truth.

If you trace the origin story further back, you find a family scene. Kenny Loggins wrote it as a gift for his brother Danny on the birth of his son, Colin—first showing up on a Gator Creek release before becoming an early signature for the new duo. It’s a dedication more than a declaration, a circle sketched in pencil rather than chiseled in stone. The song’s path is unglamorous and perfectly fitting: from a personal note to a wider room.

What astonishes, years later, is how completely the recording trusts air and space. The arrangement leans on acoustic strings and barely there rhythm—light percussion that moves like a hand on a tabletop, and a bass line that never forces its way to the front. The credits list a small, sympathetic unit: Loggins in the lead with his classical acoustic, Messina in close harmony, and color from violin and keys, with Michael Omartian appearing on a restrained keyboard part that swells in and out like breath. No one strains for spotlight; even the supporting lines arrive like good advice—helpful, brief, and gone before they overstay.

The vocal blend is the axis. Loggins carries the melody with that bell-clear teenage earnestness he never entirely lost, while Messina’s harmony tucks itself a half-step of intimacy behind him. Their phrasing is tellingly unfussy: long, even notes that sit square in the pocket; syllables that resolve a beat later than expected; a vibrato that doesn’t appear until the tail of a phrase, like a smile you only catch when someone turns their head. You can chart the emotional arc by the sustain: the longer the held note, the more the song insists on patience as a form of love.

There’s one moment I always wait for—the first time the harmony slips from parallel to something slightly more shaded, as if the line itself were shifting its weight in the chair. You hear the room around them, too. Not reverb gloss—air. The kind of space that tells you they trusted a performance more than a polish. On good studio headphones, the edges of their breath lift like the paper of an old letter, making the intimacy literal without ever turning it into spectacle.

The economy of the arrangement could read as caution, but it feels like confidence: a knowledge that the lyric—and the way it’s lived—can carry the scene. This isn’t a declaration from a mountaintop; it’s a quiet promise spoken across a kitchen table. The strings don’t swell to tell you when to feel; a small figure on the keys does that with two notes, and the violin draws a thin beam of light across the floor. If you’re listening closely, you notice how the dynamic never breaks the frame. The band rises and falls in one body, like breath in sleep.

“This song doesn’t try to change your life; it offers to hold your life with you.”

Part of the track’s afterlife owes to the way it traveled. Anne Murray, recognizing the song’s soft backbone, recorded a cover in late 1972 that reached the U.S. Top 10 across pop and easy listening charts in early 1973—a tribute to the tune’s cross-genre sturdiness and to the interpretive generosity of Murray’s own voice. But listen back to Loggins & Messina and you hear what made it portable: an emotional architecture designed for different rooms, different years. The lyric speaks to anyone who’s counted their fortunes in things other than money, and the melody knows how to stand still long enough for you to step inside.

When we talk about early-’70s soft rock, we often default to the big choruses and polished sheen—the radio-ready postcard. “Danny’s Song” works the other way: it’s all handwriting. The sonics reflect that approach. The six-string lead is tucked close to the center of the stereo image; the rhythm instruments refuse to telegraph drama; the supporting lines keep their elbows in. The result is a track that sounds less “produced” than “present.” It prioritizes presence—of voice, of line, of thought—over bombast.

And this presence has traveled because it meets listeners where they live. Three small stories:

-

A new parent in a dim apartment, cradling their child for the first time after a long hospital night. The world is loud in its demands, but at 3:12 a.m. the only thing that matters is the hush between words. The song finds that hush and fills it without crowding.

-

Two twenty-somethings in a used car on a winter highway, returning from a friend’s wedding with the windows fogged. They’re broke, uncertain, and incandescent with the serious joke of it all. When the harmony arrives, they both look at the windshield as if the road has widened.

-

A middle-aged couple packing a second-hand crib into a small hatchback outside a thrift store. Their plans didn’t follow the map. This tune, playing faintly over the store’s speakers, keeps them company while the future rearranges itself again.

The musicianship makes these scenes possible because it refuses to interrupt them. Hear the right hand on the keys early in the second verse—two notes, then air, then the same two notes again, placed like picture hooks on a blank wall. Hear the low string line that doesn’t act like a hook so much as a shoulder, something for the melody to rest on. Hear the way Messina glides into the top note of a harmony instead of landing on it, and how that glide says as much about compassion as any lyric could.

Because the writing is so undemonstrative, you might miss how carefully it balances particulars and universals. The specificity of a brother’s name, a child’s birth, a home-making tally—these ground the song like hand-placed stones. But the music refuses to become anecdote. It’s built for repetition, for the dailiness of love, for the commute, the grocery line, the midnight feeding. In that sense it’s a rare piece of music that invites you not to chase catharsis but to practice gentleness.

Place it in career arc and it becomes even more striking. Sittin’ In marks the start of the Loggins-Messina partnership, a meeting of a young writer’s openhearted melodies with a producer-arranger’s ear for frame and proportion—credited here in a way that reads as both practical and poetic. The union yielded an early-’70s run of tracks that lodged themselves in North American radio memory, but few were as quietly formative as this. The fact that the LP released in November 1971 on Columbia, produced by Messina, helps decode its priorities: a label with reach, a producer with taste, and a duo choosing craft over clamor.

The performance’s humility also clarifies why it was so coverable. Murray’s hit version retains the spine while changing the body: key, texture, radio focus. Yet the blueprint holds. And there’s something tender about that: a song born for one family that keeps finding other families to live in. When listeners say the tune “found them” at a specific life moment, they usually mean it made ordinary hope sound like something you could carry in your pocket without breaking it.

Sonic detail keeps the recording fresh across systems. On a decent living-room rig you feel the low end more than you hear it; on nearfields you notice the articulation of the fingerboard; and if you move to a phone speaker it still holds shape, proof that a strong melody can survive the smallness of a modern world. The track is an argument for dynamics as empathy: play just a little softer when the voice leans in, and a little wider when the line needs room to turn.

It’s also, crucially, a lesson in restraint. There are moments in the late bridge where a more bombastic production might have thrown in a big drum fill or a stacked vocal pad. Loggins & Messina keep their discipline. The energy comes from release—phrases that lengthen, vowels that open—and then the music steps back, as if to say, “that’s enough.” Restraint feels like a moral choice here, not merely aesthetic: love expressed without performance, gratitude without spectacle.

If you’re the kind of listener who likes to mark up scores, you’ll find “Danny’s Song” especially kind to those who live with songs on paper. The harmonic movement is simple but generous; it invites a hand on the neck and a voice a little out of practice. It’s no surprise the tune passes easily among friends, choirs, campers—anywhere someone is willing to lead. You can imagine copies of the sheet music creased at the corners from being folded into back pockets and backpacks (and, no, the song doesn’t need trained voices to work; it trusts human ones).

And because people often discover the track during season-shifts—marriages, births, moves—it becomes more than a throwback to a genre moment. It’s a companion. Put it on while you’re packing a box, while you’re sitting on a stair at dusk, while you’re letting some worry land and then pass. This is music that says the ordinary is the point; the ordinary is where we spend our lives. The extraordinary only makes a cameo.

For those who want to listen deeper, notice the micro-engineering of balance. The violin’s first entrance is narrow and high, never allowed to fight the vocal for attention. The low end rounds out when the voice needs lift, not when the arrangement needs show. And the harmony waits until it will feel like reassurance rather than decoration. Messina’s producer’s sense—knowing when to keep the frame small—remains the unsung hero of the cut.

A final word on lineage. The song’s journey—from a brotherly gift to an FM staple to a country-pop crossover via Murray—reminds us that sincerity travels better than trend. That’s why the recording feels timely even now. In a world swollen with spectacle, the most radical move is often to mean what you say and then stop. “Danny’s Song” does that, once, twice, again. And every time you return, it meets you where you are.

If you haven’t played it in a while, invite it back into your day. Let the first figure start and resist the urge to multitask. You’ll hear a writer’s early grace, a producer’s wise framing, and a duo learning how to make room for one another. You’ll hear the comfort of a familiar six-string and a single, unfancy piano line doing what great lines do—carrying more feeling than their notes would suggest. And you may find, before the last cadence, that the song has done its old work again: made the room feel a little kinder.

Listening again today, I’m struck by how thoroughly it still fulfills the promise that launched Loggins & Messina’s career: music built for mutual care, strong enough to be shared. Put it on when the room is quiet. Let it go about its gentle task.

Listening Recommendations

– James Taylor – “Sweet Baby James” — another early-’70s lullaby that turns small domestic moments into wide-screen tenderness.

– Cat Stevens – “Father and Son” — parent-child wisdom carried by unadorned acoustic lines and conversational phrasing.

– Bread – “Diary” — soft-rock clarity with intimate storytelling and discreet accompaniment.

– America – “I Need You” — open-hearted melody, close harmonies, and spacious early-’70s air.

– Anne Murray – “Danny’s Song” — the country-pop cover that took the tune to Top 10 radio without losing its core hush.