The tape starts cold in my mind: a quick count-off swallowed by a bassline that hits like a swinging pendulum, then the drumkit sets a strict grid and the voice arrives—urgent, tall, a touch theatrical. You can almost feel the air of 1966 London in the proximity of the microphone, the vocal sitting slightly forward, as if nudging the band onward. This is Los Bravos’ “Black Is Black,” the Spanish group’s calling card and the title track of their debut album of the same name, released in 1966. It’s the moment the band steps from local promise into international orbit, guided by producer Ivor Raymonde, a studio craftsman whose hands were all over the session. Wikipedia+1

The song first appeared as a single in the summer of ’66 and very quickly erased borders. It surged in the UK, cracked the US market, and topped charts in Canada—an improbable triangulation for a group whose roots were on the Iberian Peninsula. The achievement is routinely cited as the first truly international rock hit by a Spanish band, and its success became the axis around which the group’s brief, bright career turned. Wikipedia+1

Raymonde’s production is sleek but not sterile. The rhythm section is tight as a drumhead, the bassline rendering the minor-key hook in bold, unblinking strokes. Rhythm guitar slashes against the downbeat; a tambourine slices the upper mids like a shard of light; and somewhere in the midrange, an electric organ glues it all together—appropriate for a band that included an organist among its core members. The arrangement does not balloon into orchestral excess; it’s a lean machine that knows restraint is its own kind of bravado. nostalgiacentral.com

The voice is everything here. Mike Kogel (later known as Mike Kennedy) sings with a high, almost keening intensity that listeners of the day compared to Gene Pitney. It’s dramatic but not overwrought, riding that narrow line between pop showmanship and rock insistence. Kogel’s phrasing lengthens on the vowels, adding tension, then snaps back on the consonants, as if puncturing the fabric of the groove. That elastic push-and-pull is the record’s heartbeat. Wikipedia

And yet, “Black Is Black” is not a flamboyant piece of music. Its power is in its geometry—the way each element slots into a repeating pattern without feeling repetitive. The drums keep the corridor narrow; the bass takes measured steps down that familiar minor path; the guitars jab in opposition; the organ paints the walls. When Kogel climbs at the end of a phrase, you feel a window fly open.

Many sources note the song was penned by the British writing team of Michelle Grainger, Tony Hayes, and Steve Wadey. That fact matters because it explains the curious cosmopolitanism of the record: a Spanish group presenting an English-language hit written by British songwriters and produced by an English arranger-producer. The nexus gave the single a shape that traveled easily across markets, from pirate-radio spins in the UK to stateside playlists. Wikipedia

What strikes me on re-listens is the record’s spatial design. The vocal sits close—almost no air between Kogel and us—while the band drops half a step back. There’s a pocket of room reverb around the drums, enough to outline the kit without sending it into cavern territory. The guitar is wiry rather than thick; if there’s any saturation, it’s tasteful, with the attack of the pick clear on the string. The organ sustains the harmony like a long shadow cast down a city street.

“Black Is Black” doesn’t reach for stadium drama. Instead, it achieves inevitability. The two-minute-fifty-nine-second runtime (listed on many releases) is just the right length for a groove that locks early and refuses to wobble. Wikipedia

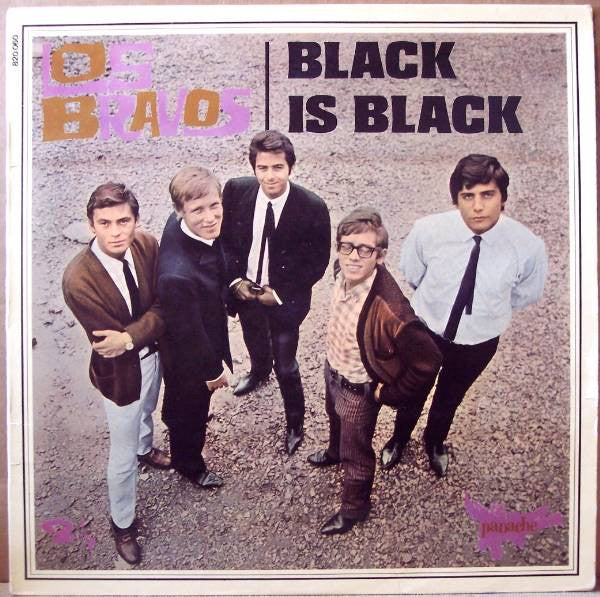

Consider where the track lands in Los Bravos’ brief arc. The band coalesced from members of Madrid’s Los Sonor and the Mallorca scene; they signed and recorded under Raymonde’s guidance, then rode “Black Is Black” onto international stages in a flash. The debut album arriving the same year turned the single into a banner, its title elevated to the nameplate of the LP across Spain, the UK, and the US—on Columbia in Spain, Decca in Britain, and Press Records stateside. This was branding by momentum: the hit defined the project, and the project gave the hit a home. Wikipedia+2Wikipedia+2

A word on charting without drowning in numbers: “Black Is Black” was a top-tier hit in the UK, a top-five in the US, and a number one in Canada, a trifecta impressive enough to secure the group’s foothold outside Spain. Those broad placements are well-documented across official chart histories and music references, and they remain a key part of the song’s narrative half a century later. officialcharts.com+1

What about texture? Close listening suggests the drummer favors a crisp, dry snare with minimal ring. The hi-hat counts like a metronome but adds flourishes as the chorus approaches, opening slightly to widen the soundstage. The bass, likely run through a modestly driven amplifier, prioritizes clarity over warmth—every note is a rung on a ladder. The guitar isn’t showy; it’s a tone-colorist’s instrument here, throwing percussive chords like sparks on steel. If a piano is present at all, it’s not front-of-mix; the song’s harmonic canvas leans on organ and strummed strings rather than hammer-and-felt clatter.

Raymonde’s touch is crucial. As producer, he was known for tasteful arrangements that favored contour over clutter. You can hear that ethos in the way “Black Is Black” resists the temptation to decorate itself with unnecessary fills. In a season when studio pop often grew ornate, this track values muscular minimalism. Wikipedia

The B-side, “I Want a Name,” is sometimes cited in discographies and label copy; it reminds us of the single’s role as a portable billboard for the album that followed. Even if listeners didn’t buy the LP, the single alone delivered a fully formed identity: European beat with a noir tint. Wikipedia

I keep coming back to the vocal timbre. There’s a gleam to Kogel’s upper register that cuts cleanly through the band without sheer volume doing the work. The vibrato is narrow, controlled; the sustained notes don’t wobble so much as hover, like a blade held steady above the groove. The phrasing—especially on the final chorus—stretches the meter just enough to tease a breakdown that never comes. Restraint wins the day.

Two short stories, because songs this iconic gather lives around them:

A friend once told me “Black Is Black” soundtracked his early-morning drives to a bakery job in the pre-dawn dark. He’d park on a side street, keep the engine running, and let the song finish before clocking in. Twenty years later, he says the bassline still smells like yeast and cold air. The opening bars were his private rallying cry—three minutes of borrowed posture before lifting trays and counting change.

Another memory: a café DJ in Barcelona, just as the evening turned from chatter to low laughter and clinking glasses. She segued from a modern synth track into Los Bravos without announcement. Nobody in the room, most of them tourists, recognized the transition at first. But the moment Kogel started singing, heads rose. The minor-key mood sharpened the room; pairs leaned closer. Vintage, yes, but not embalmed.

“Black Is Black” is light on ornament, heavy on intent.

The lyric’s economy helps. The sense of pursuit—wanting back what’s gone—sits perfectly in the firm structure of the beat. If the guitars hint at desperation, the rhythm section keeps its composure. That contrast—glamour versus grit—is the record’s engine. The voice dramatizes; the band disciplines.

Set against other hits of 1966, the track feels both of its era and slightly askew. There are no psychedelic freak-outs here, though some sources tag it “psychedelic rock” for its minor palette and moody drive. You won’t find the jangle of Merseybeat nor the bluesier swagger of American garage. Instead, there’s a cosmopolitan beat group working with precision, trimmed to radio length, packed for export. Wikipedia

To appreciate that precision, try a focused listen on good studio headphones; you’ll hear how the organ’s sustained tones bind the arrangement, how the tambourine brightens the choruses, how the bass shapes the song’s emotional arc by barely moving. The track rewards attention at low and high volume; it scales gracefully. And while it’s not a typical showcase for virtuosity, the touch on the guitar is immaculate—small inflections, big intent.

A brief note on context within the band’s history. The rapid lift of 1966 led to further singles and an intense schedule, and the group’s story took darker turns in the late ’60s, including tragedy and lineup changes. But if you step back, you see “Black Is Black” as the keystone—the door they walked through into the broader pop world. For many, it remains the definitive Los Bravos message. theseconddisc.com+1

On the album front, the 1966 LP bearing the same name curates the band’s early identity. Track listings varied by territory, a common practice then, but the presence of the hit across versions made it the anchor, the reason browsers in record shops would take a chance on a Spanish group with a striking, shadowy sleeve. The labels differed by market—Decca in the UK, Columbia in Spain, Press in the US—underscoring how the song’s appeal traveled. Wikipedia+1

There’s a temptation to call “Black Is Black” simple. That misses the point. Simplicity here is not a lack of ideas but a discipline in presenting only the necessary ones. The minor progression is familiar, but the way Los Bravos inhabit it—the punctuation of the snare, the mechanical yet human swing of the bass, the organ’s velvet sustain—makes the record feel inevitable. You don’t argue with it; you accept its momentum.

If you’re listening on a modern system, the track’s compact dynamic range means it punches cleanly through everyday noise. In a living room with modest home audio, it fills space without bloat; on portable speakers, the bassline still defines the room. The mono and stereo mixes that have circulated over the years maintain that muscular center, which is probably why the single still feels sturdy in playlists alongside newer recordings.

Because we often talk about performance and neglect craft: the writing team’s melodic economy deserves mention. The hook cycles so efficiently that it almost turns into a mantra. You think you’ve had enough—and then you let it roll again. That repeatability, more than any studio trick, is what gave the single its longevity across countries and formats. Wikipedia

It’s easy to imagine the track introduced on pirate radio in ’66, the DJ’s voice ducking out as the bass kicks in, a generation hearing a Spanish band sound unmistakably global. The single didn’t need a manifesto. It needed two minutes and fifty-nine seconds to show how a beat group could be cosmopolitan without losing urgency.

The question I ask with songs this canonical is whether they invite re-listening, not out of obligation but curiosity. With “Black Is Black,” the answer is yes. On each pass, the voice’s slightly metallic edge tells you something new about the lyric; the organ’s glide reveals how the harmony is stitched; the guitar’s clipped strums remind you that a small gesture, placed exactly, can define an entire record.

I also find myself attentive to what isn’t there. No ornamental strings. No extended middle-eight. No gratuitous solo. The restraint feels grown-up, especially for a group newly arrived on the international stage. That, more than the hook alone, is why the record endures: it trusts the listener to meet it halfway.

If you’re exploring further, know that Los Bravos released additional singles in 1966 and beyond, and their compact discography includes moments of brightness and experiment. But if you only have time for one cut, this is where to start, not because it’s the most famous but because it’s the most complete. It’s the rare hit that sounds finished, not polished within an inch of its life, but complete—nothing to add, nothing to subtract.

As for how to hear it today, a modern remaster through a reliable service will suit most. If you chase details—the slight lift of the tambourine on the final chorus, the vocal’s final glide—playing a lossless file through decent gear or even a small upgrade into premium audio can make those edges pop without changing the song’s character. And if you’re a musician peering under the hood, a close read of the harmonic skeleton yields quick lessons in economy, from how the bass directs the progression to how the organ masks transitions. Wikipedia

One last thought, because minor-key pop this catchy always tempts analysis past usefulness. Sometimes the measure of a recording is whether it catches a room off guard. “Black Is Black” still does. In bars, cafés, and car stereos, that opening bassline asks for a little posture, and suddenly the night has contours. That’s not nostalgia; that’s design.

Listen again. Let the bass count your steps. Let the voice open a window. The song knows exactly how much to give.

Listening Recommendations

-

The Walker Brothers — “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine (Anymore)”

A similarly dramatic 1966 production where baritone vocals and orchestral pop meet a moody, European sense of scale. -

The Zombies — “She’s Not There”

Minor-key cool with electric piano and sly rhythmic turns; a blueprint for economy and atmosphere in British beat. -

The Righteous Brothers — “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’”

A lesson in restraint and swell, balancing studio grandeur with emotional directness. -

The Easybeats — “Friday on My Mind”

Beat-group urgency channeled into disciplined hooks and big-room energy. -

The Left Banke — “Walk Away Renée”

Baroque pop elegance that complements Los Bravos’ sleek minimalism with strings and sighing melody. -

Belle Epoque — “Black Is Black” (1977)

A disco-era reimagining of the same song that shows how the core hook thrives in a different decade’s dancefloor grammar.