The transistor radio, that constant companion of the mid-sixties teenager, had a way of flattening everything into an audible, vibrating thrill. Yet, some sounds simply defied compression. They burst through the static, a sudden, high-fidelity thunderclap in the tinny air. Lou Christie’s “Lightnin’ Strikes” was one of those records—a glorious, over-the-top explosion of anxiety, desire, and pure pop theatrics.

I imagine the control room at Olmstead Studios in New York on September 3, 1965, the day this monumental piece of music was captured. The air would be thick with cigarette smoke and the focused tension of seasoned session musicians. Here was a composition co-written by Lou Christie, or Lugee Sacco as he was born, and his eccentric, much older collaborator, Twyla Herbert. Their partnership was already responsible for earlier hits like “The Gypsy Cried,” but this track felt like a grand final statement.

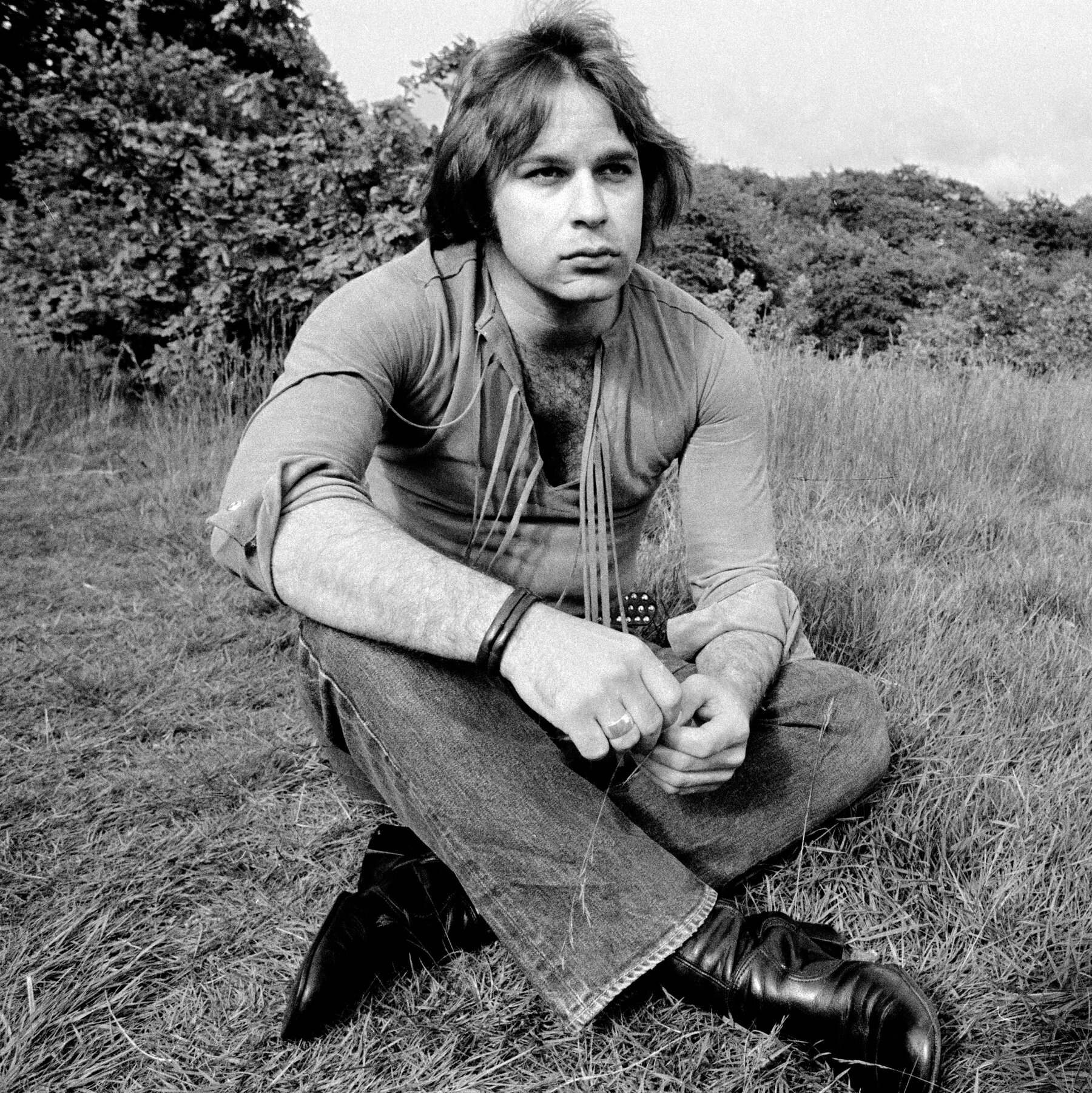

This was Christie’s comeback. After scoring his first national hits, his career had been interrupted by a stint in the Army Reserves. He returned and signed to the MGM label, ready to re-establish himself in a rapidly changing pop landscape, one increasingly dominated by the British Invasion and the burgeoning sounds of folk-rock. Yet, “Lightnin’ Strikes” looked back, while simultaneously creating something utterly unique. It was firmly rooted in the New York vocal-group tradition, then catapulted into the baroque pop stratosphere.

The story of the single’s release is legendary: MGM reportedly disliked the track and initially tossed the master. It took dedicated promotion from Christie’s new management in California to force the label’s hand. When it was finally released in late 1965, the song caught fire, climbing the charts through early 1966, eventually reaching the top spot in both the US and Canada. It was a massive international success, cementing Christie’s place in history as a falsetto superstar. The song was the title track for his 1966 album, Lightnin’ Strikes, his first full-length for MGM.

The track’s very DNA is melodrama. It begins in a deceptively sweet, almost church-like fashion. A delicate, tinkling piano figure sets the scene, supported by a mournful baritone sax line. The texture is initially light, a dreamy prelude to the coming storm. Christie’s voice enters, restrained for a moment, detailing a romantic commitment in what he calls a “chapel in the pines.”

But beneath the surface sincerity, a tension builds. The rhythm section is locked into a tight, mid-tempo march, powered by Buddy Saltzman’s firm, unhurried drums. Then, as the verse progresses, the arrangement begins to fray. The piano pounds out crashing, dissonant chords, like flashes of lightning or perhaps the narrator’s sudden, internal crisis.

This is where the song truly lives: in the stunning, almost psychotic contrast between the verses and the chorus. The verse is confession, the chorus is catharsis.

The genius behind this sonic escalation belongs to the producer and arranger, Charles Calello, a former member of The Four Seasons. Calello understood exactly how to wield an orchestral palette for maximum emotional impact. He takes a simple pop structure and dresses it in grand, near-operatic clothes. The arrangement swells, driven by the female backing vocalists—Bernadette Carroll, Peggy Santiglia, and Denise Ferri, known as the Delicates—who wail a perfectly pitched, desperate “STOP! STOP!” against Christie’s building intensity.

Christie’s trademark four-octave falsetto is the star. It’s not the sweet, smooth falsetto of a standard doo-wop singer; it’s strained, operatic, almost a cry of desperation. When he shrieks, “I can’t stop! I can’t stop myself!” his voice seems to break free of gravity, an aural representation of the irresistible, morally dubious urge he describes in the lyrics.

Thematically, the song is a study in 1960s sexual double standards. The narrator, ostensibly pleading for a girlfriend he can trust “to the very end,” justifies his own infidelity by claiming his urges are uncontrollable—it’s nature, “like the rain and the fire.” The lyrics are smug, controlling (“live by my rules, little girl”), yet the sheer glamour of the arrangement somehow makes the problematic nature of the narrative palatable, even thrilling, for the casual listener.

The instrumentation is a masterclass in controlled chaos. Beyond the brass section—including Joe Farrell and George Young on baritone sax—that adds a gritty punch, listen closely to the guitar. Ralph Casale’s contribution is a nervous, stuttering, tremolo-laden solo overdub that cuts across the melody with electric anxiety. It sounds like a heart frantically skipping beats, or perhaps the static charge before a storm hits. This attention to detail elevates the piece of music far beyond a simple chart hit. The whole mix, especially when heard on a quality vintage console or premium audio system, is a dizzying swirl of high-end chime and low-end pulse.

What “Lightnin’ Strikes” ultimately sells is a feeling—the moment of losing control, the rush of a sudden, forbidden urge. It is about the glorious, terrifying chaos of teenage hormones meeting an adult world of consequence. It’s why, decades later, the track still feels alive, vibrant, and a little dangerous.

This enduring vitality is the magic of great pop.

“The best pop song doesn’t resolve tension; it puts it on a loop and paints it gold.”

For me, this song is tied to a specific kind of memory: the moment I finally understood the glamour of moral ambiguity in music. I remember putting the song on shuffle during a late-night drive, the city lights streaking past the windows like distorted reflections of sound. The dramatic arrangement turned the mundane act of driving into a cinematic escape. This is a track that demands you inhabit its drama, whether you agree with the protagonist’s dubious philosophy or not. It’s a sonic theater, and the price of admission is a brief, glorious surrender to the high-note hysteria. It is a reminder that even in the most polished pop, a touch of genuine weirdness can create an everlasting artifact.

We’re all looking for the next surge of electric feeling, a reminder that we can still be swept away. This track delivers that jolt in a perfectly sealed, three-minute package. It wasn’t the kind of song that required you to take guitar lessons or understand complex harmonies; it simply asked you to feel. And when Christie’s falsetto hits that final, soaring peak, you absolutely do. This isn’t just a record; it’s an event.

Listening Recommendations (Adjacent Moods and Arrangements)

- “Rag Doll” – The Four Seasons (1964): Shares a similar baroque pop sensibility and features a soaring, multi-layered falsetto vocal style.

- “He’s Sure the Boy I Love” – The Crystals (1962): For the dramatic arrangement and the cinematic use of backing vocals and deep studio reverb, reminiscent of the Wall of Sound.

- “A Lover’s Concerto” – The Toys (1965): Connects through the use of classical-influenced piano instrumentation wrapped in a quintessential 1960s pop production.

- “I’m Gonna Make You Mine” – Lou Christie (1969): A later, equally powerful hit by Christie that maintains his dramatic vocal attack and high-drama arrangement.

- “Two Faces Have I” – Lou Christie (1963): Another Christie/Herbert collaboration that showcases the early development of his dual vocal style (falsetto/baritone) and theatrical style.