The best songs feel less like a performance and more like a whispered confession stolen from the dim hours just before dawn. You hear the scrape of a chair, the hollow clink of glass, and the thick, unburdened silence that follows a truth finally spoken. Kris Kristofferson’s “Loving Her Was Easier (Than Anything I’ll Ever Do Again)” is a song built entirely from that specific, heavy quiet. It is not an anthem of dramatic loss, but a shrug of ultimate, weary resignation.

This piece of music arrived in 1971, a pivotal year that saw Kristofferson transitioning from Nashville’s most celebrated, hard-living songwriter to a formidable recording artist and burgeoning film star. He was, by many accounts, a walking contradiction: a Rhodes Scholar, an ex-Army Captain, and now the gritty, sensual voice of a new, literary country sound. The track anchors his second album, The Silver Tongued Devil and I, released on Monument Records. Following the critical praise for his 1970 debut, Kristofferson, this sophomore effort was produced, like its predecessor, by the crucial Nashville figure Fred Foster.

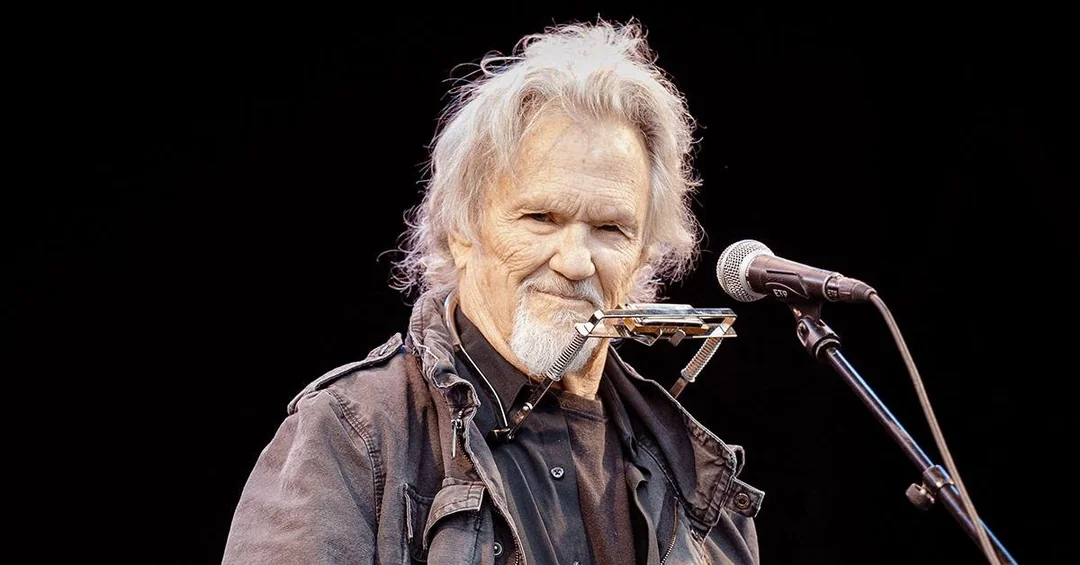

The album captured Kristofferson at the peak of his poetic outlaw phase, before Hollywood fully claimed him. It was a time when his raw, gravel-etched voice—which he himself famously disparaged—was the perfect vessel for lyrics that were too intelligent, too frank, and too messy for the pristine polish of conventional country radio. While his contemporaries and peers were scoring massive hits with his compositions (“Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down,” “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” “Me and Bobby McGee”), “Loving Her Was Easier” was a crucial hit that proved Kristofferson, the singer, could connect with a broad audience. It charted well on both the Billboard Hot 100 and the Easy Listening charts—a testament to its crossover appeal rooted in universal, adult sorrow.

The Sound of Wistful Drift

The brilliance of Foster’s production lies in its deceptive restraint. The arrangement never competes with the lyric; it only underscores the narrative’s central emotion: the slow, painful drift of memory. Kristofferson’s initial version rejects the dramatic, sweeping orchestrations that often characterized the late-era “countrypolitan” style. Instead, we are drawn in by the intimacy of the rhythm section, its pulse subtle, almost hesitant.

The foundation is an exquisite tension between the acoustic guitar and the piano. The acoustic guitar work is simple, fingerpicked lines that give the track a bare, folk-ballad feel. It provides a skeletal support for Kristofferson’s vocal delivery, which is more spoken than sung, full of cracked vulnerability. The piano enters softly, providing chords that hang in the air, sustained by a generous, warm reverb—a sound that evokes the cavernous, empty space left by a lost lover.

As the track progresses, the Nashville session musicians subtly build the sonic landscape. There is a prominent, weeping quality to the steel guitar, its slow glissandi functioning almost as a second, wordless voice, aching where Kristofferson’s own voice holds back. Then, the strings: they do not swell into a grand, cathartic moment but rather emerge, thin and high, almost like a halo of light around the memory the narrator is reliving. The dynamics of this piece of music are masterful; the volume rarely rises above a reflective mid-level, forcing the listener to lean in, to become privy to the private moment of recollection.

The lyric itself is a marvel of economical imagery. It doesn’t rely on narrative specifics, but on sensory impressions and natural metaphor. She was “like the wind that catches on a lazy summer breeze,” and “like the sunlight, shinning through a lazy summer haze.” The repetition of “lazy summer” suggests a time of effortlessness, a natural state of being that is, crucially, now unattainable. The simplicity of the language is its ultimate sophistication. It cuts through the noise of complicated relationships to reveal the simple core: some connections are just easier than everything else. The tragedy isn’t betrayal or a fight; the tragedy is the sheer effort required to live without that effortless love.

“His voice, with all its beautiful imperfections, elevates the song beyond a simple lament to a chronicle of profound personal failure.”

The central phrase, “Loving her was easier than anything I’ll ever do again,” is the punchline of a failed life. It’s not an exaggeration; it’s a terrifying acceptance of a future where all subsequent efforts—in work, in new relationships, in just getting by—will feel impossibly burdensome by comparison. It is the existential dread of the mediocre future, where the peak of one’s emotional life is already in the rear-view mirror. I am often drawn back to this moment, a quiet realization that hits like a shot of cold truth, especially when I listen back through my premium audio setup. It is a song that rewards clarity and sonic depth.

The Legacy and The Shadow

Kristofferson’s delivery—that infamous “frog” croak—is the key. Unlike many of the polished vocalists who covered this song, he sounds authentically tired, authentically broken. There is no attempt at vocal acrobatics or high-note showmanship. The restraint is the art. He doesn’t need to scream his pain; the simple fact of his weary phrasing tells the whole story. The moment he hits that final word, again, the note is allowed to fray, its edge ragged with unexpressed sorrow.

This song exists on an album that, in many ways, defined the singer-songwriter movement’s turn toward introspection and raw confession. It showed that country music’s themes—the road, the drink, the lost love—could be treated with the literary weight of a John Updike short story. Kristofferson, along with contemporaries like Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings, was challenging the Nashville establishment, pushing the boundaries of what was considered acceptable subject matter for the airwaves. This particular song, though, managed to smuggle its deep melancholy right past the gatekeepers, simply because its melody is so accessible and its emotion so nakedly honest.

It is interesting to note how often students, learning from guitar lessons or transcribing the chord changes, focus on the relatively simple progression. The structure is deceptively straightforward, yet the harmonic shifts in the chorus are what make the resolution of the title line so heartbreakingly final. The music sounds like a settling, a falling action, even as the words describe an impossibility. It is a trick that only the masters of the craft can pull off: simplicity deployed with devastating emotional effect. This song remains one of the most covered tracks in the Kristofferson catalogue, proving its universal appeal, but few have ever matched the defeated authority of his original reading. It is a touchstone of the Outlaw Country movement, a moment of fragile beauty surrounded by the gritty bravado of his other work. It is an honest reckoning, a moment of looking in the mirror and accepting the heavy cost of freedom and a life lived without guardrails. A re-listen today is a reminder that the quiet ache is often the deepest wound.

Listening Recommendations

- “For the Good Times” – Ray Price (1970): Shares the same Fred Foster/Kris Kristofferson lineage and features a similar, mournful countrypolitan string arrangement.

- “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” – Johnny Cash (1970): Another Kristofferson composition that captures the same sense of post-party loneliness and existential hangover.

- “Help Me Make It Through the Night” – Sammi Smith (1971): A contemporaneous recording of another Kristofferson classic that utilizes a minimal, intimate late-night instrumentation.

- “A Box of Pictures” – Townes Van Zandt (1972): Captures the quiet, devastating sense of reflecting on a past relationship with no hope of return, delivered in a similar weary vocal style.

- “I Can’t Help It (If I’m Still In Love With You)” – Willie Nelson (1971, Yesterday’s Wine): An example of the bare, honest country-folk sensibility that emerged alongside Kristofferson’s early solo work.

- “She’s Acting Single (I’m Drinking Doubles)” – Gary Stewart (1975): A later country song that perfectly articulates the specific, alcohol-soaked despair and resignation that runs through Kristofferson’s best work.