The air in the room is thick and sweet, smelling faintly of sweat, varnish, and something indefinable, something electric—a ghost of a thousand spilled nights. The needle drops onto a worn, beloved seven-inch, and the noise level in the dark, wood-floored hall immediately ratchets up. You can feel the change in pressure, the collective anticipation of a thousand dancers who know exactly what’s coming. This is the moment a truly special piece of music transforms from mere recording to communal ritual. This is the scene that surrounds Marv Johnson’s 1969 marvel, “I’ll Pick A Rose For My Rose.”

For many, the narrative of Motown is a clean, bright timeline of the Supremes, the Temptations, and Marvin Gaye. But if you look closely at the foundation, right there with the cornerstone, you find Marv Johnson. He was, literally, the first artist to release a single on Berry Gordy’s Tamla label in 1959. Yet, by the time the sixties were closing, Johnson was a figure whose U.S. recording career had cooled, shifting more toward an internal Motown role in sales and promotion. His final singles on the Gordy imprint struggled to connect stateside.

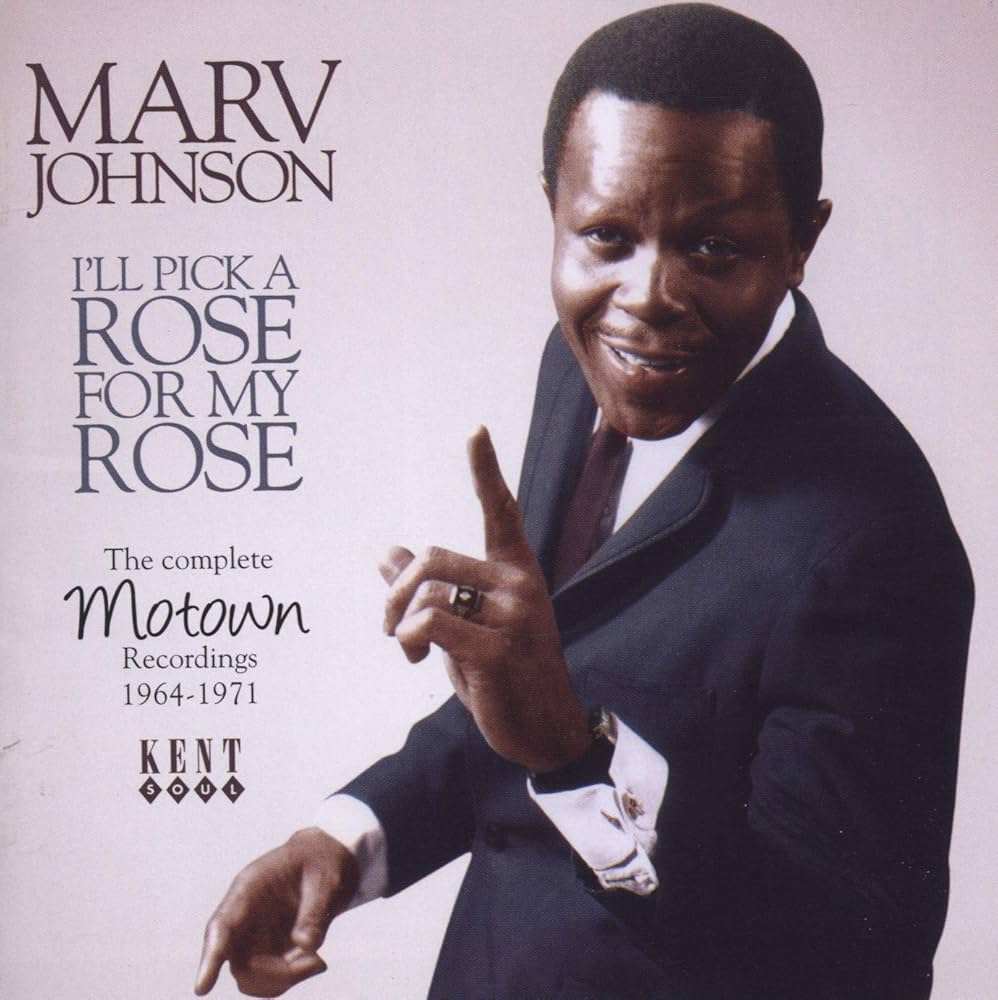

That context makes the story of “I’ll Pick A Rose For My Rose” all the more poignant. Released as a single in 1968 in the United States on the Gordy label, it was effectively ignored. But across the Atlantic, where an entire subculture was already obsessively compiling forgotten Motown and other soul records, it found a second, ferocious life. The UK’s nascent Northern Soul movement elevated this overlooked track to a Top 10 chart hit in early 1969, an utterly validating moment for an artist who had been sidelined by the machine he helped build. Its success in Britain was so significant that Motown’s British arm, Tamla Motown, compiled and released an album named after the track, I’ll Pick A Rose For My Rose, to meet the demand—an album that was never issued in the U.S.

The track itself is a testament to the sophistication of Motown’s late-sixties Detroit sound, sitting comfortably between the raw thump of early soul and the psychedelic swirl of its progressive late-period work. Co-written by Johnson himself, alongside James Dean and William Weatherspoon (who also served as producers), the song is not a simple, buoyant pop structure. It’s a beautifully layered arrangement that leverages the full emotional spectrum of the studio orchestra.

From the first two beats, you’re captured by the driving, relentless rhythm section—the heartbeat of the record. The drums, mixed punchy and forward, lay down an insistent four-on-the-floor beat, perfectly calibrated for a dance floor that values propulsion above all else. Beneath that, the bassline thumps a complex, walking pattern, more melodic than simple root notes, giving the track a grounded, propulsive swing.

Then the strings enter, not as saccharine adornment, but as a swell of high drama. Their texture is slightly coarse, recorded with a wide, almost cinematic stereo spread that adds a crucial depth to the soundstage. They execute tightly written, ascending and descending figures that mirror the desperation and hope in Johnson’s vocal. This is a Motown trademark, yes, but here it’s deployed with a mature restraint, emphasizing the grand scale of the protagonist’s emotional plea.

Marv Johnson’s voice, a powerful, richly textured instrument, takes center stage, and this is where the song truly ascends. He is a master of the emotive, slightly rough-hewn delivery, capable of hitting a soaring sustained note without ever slipping into histrionics. He delivers the complex lyric—a man reflecting on his past mistakes, promising to return with a token of enduring affection (the titular rose)—with an earnest, almost vulnerable urgency. He’s not pleading; he’s stating a truth he’s finally recognized.

The mid-section instrumentation, before the final, cathartic chorus, is where the arrangement’s intelligence really shines. A sharp, rhythmic guitar chop plays a crucial off-beat role, adding a percussive texture that pushes the rhythm even harder. This is countered by brief, arpeggiated figures from the piano, which provide harmonic grounding and a splash of bright timbre against the low-end rumble. The interplay ensures the piece of music is dense and full without ever feeling cluttered, a common pitfall of large-ensemble soul productions.

“The greatest songs don’t just ask to be heard; they demand to be felt, experienced in a physical, sweat-drenched, communal way.”

It’s an expensive-sounding production—the kind of work that demands appreciation through premium audio equipment to fully resolve the interwoven instrumental lines. The arrangement is complex enough to make you consider ordering a copy of the sheet music, just to marvel at how many moving parts work in such perfect sync. This is the Motown Sound at its peak of orchestral power, but filtered through the narrative of an underdog artist. The contrast between the slick, sweeping orchestration and the raw, pleading grit in Johnson’s vocal is the tension that makes the song timeless. It perfectly captures the glamour and the desperation of the soul era.

In the UK, particularly among the dedicated soul enthusiasts who met in dance halls like Wigan Casino and the Twisted Wheel, this record wasn’t just a hit; it was a cornerstone of the identity. Its fast-paced tempo, dramatic string arrangement, and deeply felt vocal delivery checked every box for the Northern Soul scene. It became one of the famed “three-minute masterpieces,” played well past its original expiry date, granting Marv Johnson a legendary status in a niche that transcended his momentary chart success. It’s a glorious reminder that great art often needs a second, passionate audience to truly find its moment. We should all put this on and listen to it again tonight—not just as an archival curio, but as the ecstatic, utterly compelling dance record it remains.

Listening Recommendations

- The Flirtations – “Nothing But a Heartache” (1968): Shares the same dramatic, orchestral sweep and a powerful female vocal delivery.

- The Chairmen of the Board – “Give Me Just a Little More Time” (1970): Features a similar energetic tempo and sophisticated, slightly later Motown/Invictus production style.

- Dobie Gray – “Out on the Floor” (1966): A foundational Northern Soul anthem with the same propulsive beat and soaring, emotionally charged vocal.

- The Isley Brothers – “This Old Heart of Mine (Is Weak for You)” (1966): A classic Motown track that features a similarly fervent lead vocal over an exuberant, hard-driving arrangement.

- Frank Wilson – “Do I Love You (Indeed I Do)” (1965): Another Motown single that became a massive Northern Soul hit due to its rarity and high-energy pace.

- Jimmy Ruffin – “Gonna Give Her All the Love I’ve Got” (1967): Excellent example of a mid-tempo Motown ballad transitioning into a deeply emotive, high-production number.