When Love Is Loud Enough to Shake the World—but Honest Enough to Draw a Line

There are love songs, and then there are confessions. When Meat Loaf unleashed “I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That)” in August 1993, it arrived not as a gentle whisper of romance but as a full-blown operatic proclamation—one that dared listeners to sit still, listen closely, and feel everything at once. Written and produced by Jim Steinman, the track served as the thunderous lead single from Bat Out of Hell II: Back into Hell, and its impact was immediate and overwhelming.

Against every industry rulebook, the song dominated the charts despite its epic length. In the United States, it soared to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, holding the position for five consecutive weeks. In the United Kingdom, it reigned even longer, spending seven weeks at the top. Across Europe, Australia, and Canada, the results were the same: total conquest. That a song exceeding twelve minutes in its full album version could achieve such success in the early ’90s—an era already shifting toward tighter radio formats—felt almost miraculous. But miracles were nothing new in the world of Meat Loaf and Jim Steinman.

To understand the magnitude of this song, one must understand the history behind it. Meat Loaf and Steinman’s partnership had already produced one of rock’s most iconic albums with Bat Out of Hell in 1977. That record redefined melodrama in popular music, marrying Broadway-scale storytelling with the raw muscle of rock. Yet the years that followed were anything but smooth. Legal battles, personal tensions, and creative separation kept the two apart, turning their reunion for Bat Out of Hell II into something far more significant than a simple sequel. It felt like a reckoning—a chance to reclaim unfinished business and speak with the urgency of artists who knew time was not infinite.

That urgency burns at the heart of “I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That).” From its opening moments, the song unfolds like a miniature opera. It begins in near darkness, hushed and vulnerable, before gradually building into waves of romantic yearning. By the time the chorus arrives, the music has expanded into something colossal: roaring guitars, sweeping keyboards, pounding drums, and a sense of drama that borders on the Wagnerian. This is not subtle music, and it never pretends to be. Its power lies precisely in its refusal to shrink its emotions.

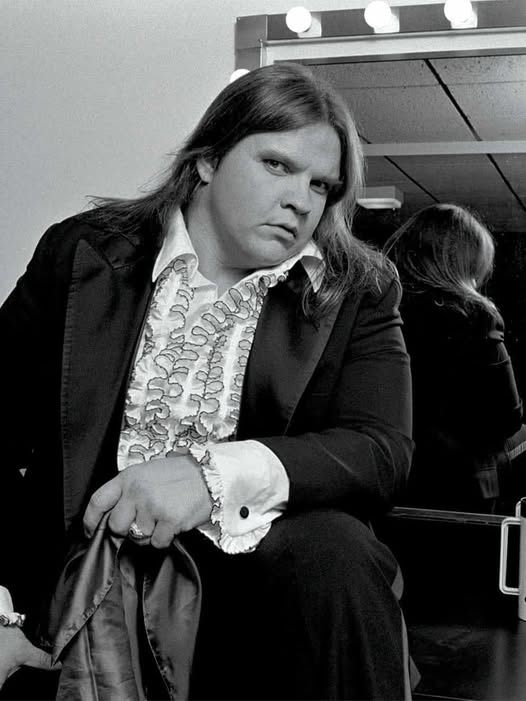

At the center of it all is Meat Loaf’s voice—cracked, massive, and achingly human. He does not sing as a distant narrator; he pleads, swears, and testifies. There is sweat in his delivery, desperation in his phrasing, and an unmistakable vulnerability beneath the bravado. This is a man laying his soul bare, insisting that his love is real, enduring, and worth the risk of humiliation. Opposite him, the female response vocals—performed by Lorraine Crosby, though uncredited at the time—serve a crucial dramatic role. She questions him, challenges him, and forces his extravagant promises to confront reality. Like a Greek chorus, her presence grounds the song’s excess and gives it emotional tension rather than empty spectacle.

For decades, one lyric has fueled endless debate: “But I won’t do that.” What, exactly, is “that”? The mystery became part of the song’s legend, spawning jokes, misunderstandings, and even parody. Yet the answer was always there, hidden in plain sight within the verses. Jim Steinman repeatedly clarified that “that” refers to moral betrayals—lying, cheating, abandoning a partner, or losing one’s integrity. The narrator will suffer, sacrifice, and even die for love, but he will not destroy love by violating the values that give it meaning. In this sense, the song is not about limitless devotion, but about boundaries.

That distinction is what elevates the song beyond theatrical excess. It argues that real love is not blind obedience or self-erasure. Instead, love is defined by conscience. The refusal embedded in the title is not weakness—it is strength. It suggests that love, to remain love, must have lines that cannot be crossed. Without them, devotion becomes hollow, and passion curdles into something destructive.

The song’s visual counterpart amplified its mythic aura. Directed by Michael Bay, the music video drew inspiration from Beauty and the Beast, casting Meat Loaf as a tormented, half-human figure seeking redemption through love. Gothic imagery, exploding candles, motorcycles bursting through cathedral walls—it was extravagant, theatrical, and completely unapologetic. MTV embraced it, and a new generation encountered Meat Loaf not as a relic of the ’70s, but as a larger-than-life storyteller still capable of commanding the cultural spotlight.

Looking back now, “I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That)” feels like a monument to an era when rock music dared to be emotionally enormous. There is no irony here, no self-conscious wink to the audience. The song believes in itself completely, and that belief is infectious. In today’s musical landscape—often dominated by understatement, minimalism, and emotional restraint—it stands as a reminder of a time when love was sung as if it were a matter of life and death.

Perhaps that is why the song has aged so well. With time, its message deepens. What once sounded like youthful exaggeration begins to resemble hard-earned wisdom. Anyone who has lived long enough to understand the cost of promises hears something different now: not just a vow to give everything, but a declaration of what must never be surrendered. Love, the song insists, is not proven by endless sacrifice alone. It is proven by the courage to say no when saying yes would mean losing oneself.

In the end, “I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That)” remains one of the boldest love songs ever recorded—grand, flawed, sincere, and unforgettable. It reminds us that devotion does not mean abandoning our moral compass, and that sometimes the most powerful act of love is knowing where the line must be drawn.