Merle Haggard often carried the weight of the road in his voice, the silent ache of moments never fully lived. In a quiet, dimly lit bar somewhere in Bakersfield, he once shared a story about a love that lingered in memory but never in touch. He spoke of long nights spent staring at a photograph, tracing the edges of a face he couldn’t hold, feeling the presence of someone who had drifted just out of reach. It wasn’t anger or regret—it was the soft, persistent ache of absence, a longing that thrummed beneath every chord he strummed. The kind of heartache that leaves a trace in your chest, a ghost of connection that never crossed the threshold of intimacy. Haggard’s songs often captured these fleeting, fragile emotions, but “We Never Touch At All” holds them raw, honest, and painfully real—like a confession whispered in the dark.

There’s a certain hour on a long drive when the highway thins, the dashboard clock feels untrustworthy, and the radio becomes a confidant. That’s where “We Never Touch at All” belongs—somewhere between midnight and the first suggestion of morning, when the mind is brave enough to admit what the daylight edits out. The song is quiet, but not fragile; poised, but not polished to the point of fiction. It’s Merle Haggard at a late-career inflection point, weighing how love cools not with a crash but a careful, gradual drift.

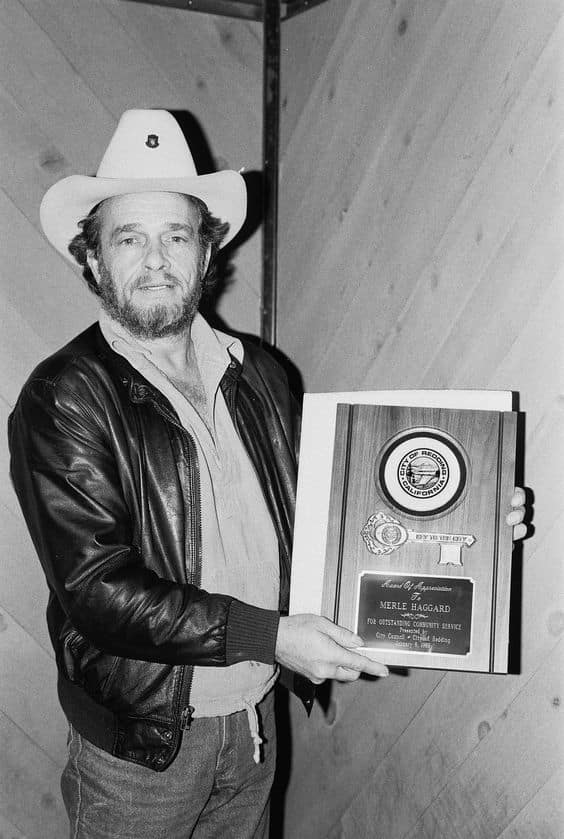

Context matters here. “We Never Touch at All” appeared on Haggard’s 1987 Epic Records release Chill Factor, a project cut with his longtime band the Strangers and co-produced by Haggard and Ken Suesov. Wikipedia The track wasn’t just an album cut; it was released as a single the following year, written by the great Hank Cochran, and it landed Haggard back on country radio in a period increasingly dominated by younger “new traditionalists.” Wikipedia+1 Within that timeline, the piece of music feels almost like a quiet argument: there’s still room for soft light and adult nuance, even as the format tilts toward flash and youthful conviction.

At first listen, the arrangement barely raises its voice. The tempo sits in a gentle sway, close enough to a ballad to invite you in, far enough from syrup to keep your attention awake. The rhythm section plays with a slow-breathing pocket, kick and snare shaping soft silhouettes rather than pounding declarations. Over that bed, you hear what Haggard does best: sing right down the center of the note, then lean on its underside with a grain that suggests a private thought shared aloud. There’s the easy sigh of pedal steel—almost certainly a nod to the Strangers’ signature textures—and a patient electric guitar that answers Haggard’s phrases like a friend who knows better than to overtalk. The piano is tasteful, pushing brief, supportive chords that lengthen the room without stealing the view.

Haggard was always a master of understatement, and you can feel his producer’s touch in the balance. Nothing is arranged to dazzle. Instruments are placed like furniture in a modest home: not expensive, but exactly where you’d sit to have the conversation. If you listen closely on good studio headphones, you can catch the air between parts—the little pockets of silence that make the lyric’s ache feel lived-in rather than staged.

That lyric matters. The title line—“We Never Touch at All”—is less an accusation than a diagnosis. It names the symptom you can’t bring up at dinner without changing the seasoning of the night. Haggard lets the words fall with conversational cadence, resisting the temptation to deliver a climactic pay-off. The restraint is the pay-off. With each verse, the singer maps an interior landscape where closeness used to be muscle memory. He lingers on the gap between habit and impulse, where couples learn to pass salt and pepper like co-workers sharing a break room table.

Part of the song’s quiet authority comes from its authorship. Hank Cochran was capable of both the lightning-bolt line and the slow bruise; here he chooses the latter. That suits Haggard, who long ago learned that heartbreak writes itself plainly when you allow it the space. The collaboration, on paper, looks almost inevitable: a veteran songwriter skilled in adult complexity and a vocalist whose timbre had grown more weathered, more conversational by the late ’80s. That pairing ends up feeling less like a summit meeting and more like a kitchen-table confession.

“Chill Factor,” the album surrounding this track, arrived at a peculiar cultural moment. Radio playlists were welcoming clean-cut, new-guard voices, and yet Haggard still carved out a top-ten presence with the title cut and a chart-topper in “Twinkle, Twinkle Lucky Star.” “We Never Touch at All,” released as the third single in 1988, reached the country singles chart’s upper half and reinforced that Haggard’s quieter instincts still carried commercial oxygen. Wikipedia+1 If you’re keeping score, that’s not just nostalgia doing favors; that’s audience recognition of craft.

Listen for dynamics. The verses are almost indoor voices; the choruses widen, but only a little. Instead of the now-standard loud/soft binary, the band uses proximity. The steel steps forward by inches; the guitar lets notes bloom longer; the piano shades the cadence. There’s no dramatic key change, no final-chorus choir. The ending respects the beginning. In a market that often equates growth with explosion, that choice reads as moral and musical clarity.

One reason the track holds up today is its production footprint. Late-’80s country could get fussy with reverb and soft-focus pads, but this mix keeps the reverb tails short and the edges intact. You can almost see the players, distributed in a semi-circle, eyes on Haggard’s phrasing. It’s not a live recording, but it preserves a live feeling: that precarious equilibrium where each instrument waits its turn and each note understands it only matters because of the silence beside it.

Micro-story one: A couple sits at a two-top in a diner where the silverware tings are louder than the talk. Their hands occupy the same table, their eyes the same menu, but their moods are traveling in opposite directions. “We Never Touch at All” comes on the jukebox—somehow both too on-the-nose and exactly right. Neither person names the song. Neither needs to. The track gives them language they aren’t ready to try on.

Micro-story two: A touring musician—maybe long past his own radio days—drives through the flattest part of the state. He thinks about the distance with his spouse back home, a distance measured less in miles than in shared chances missed. The chorus arrives and he taps the steering wheel not in rhythm, but in recognition. It is the purest kind of consolation: someone else documented the same map.

Micro-story three: A young listener who discovered Haggard through playlists—after hearing “Mama Tried” on a prestige TV soundtrack—lets “We Never Touch at All” play next. The surprises are small but real: how modern the vocal feels, how little it begs, how much it trusts the listener to do the emotional arithmetic. She texts a friend: “I thought this would be dusty. It’s not. It’s…grown.”

Sound nerds will note how the arrangement lets timbre carry meaning. The steel favors a plaintive, narrow vibrato, mirroring the lyric’s narrow bandwidth of affection. The fiddle, when it appears, skims rather than soars, like a glance that doesn’t hold. The electric guitar keeps its attack soft, its sustain modest; it doesn’t draw attention so much as it completes a sentence Haggard starts. Even the drum kit plays with the kind of restraint that refuses to dramatize what doesn’t belong to it. And then there’s Haggard’s voice—rounded at the edges, with just enough gravel to suggest years you can’t unlive. He treats the melody like a hallway: long, quiet, a place you walk to reach a door you might or might not open.

Here, too, are the resonances that connect the song to Haggard’s broader career. Early Merle grew famous for his toughness, his workingman’s eye, the way he could turn an entire social climate into a three-minute story. Late-’80s Merle didn’t abandon that, he internalized it. He became a documentarian of private outcomes: the conversations that never happen, the letters never sent, the rooms where a couple edits themselves into something survivable. “We Never Touch at All” fits that arc like a missing chapter.

If you’re mapping the song into your own listening life, consider how it reconstructs intimacy out of absence. Many ballads traffic in grand gestures—tears, confessions, the kneeling beg. This one detects weather changes: the way a voice drops, the way a weekend plan doesn’t include touchpoints, the way the door closes with one too many inches of air left in the frame. It’s a craft decision as much as an emotional one: the band gives you a perimeter, and the lyric traces the echo inside it.

A word on the literal instruments, because they’re not window dressing. The guitar provides the first human scale—a soft, mid-range strum that keeps the tempo humane and believable. The piano tucks into the pocket and issues small, supportive arguments for connection, like a friend chiming in just enough to make you feel less alone. Nothing here was tracked to stun. It was tracked to last.

The production also reminds you how warmly Haggard could sing when the material invited him to confess rather than proclaim. You feel him choose breath over belt, shading syllables with a kind of weary courtesy. That choice is pivotal: a declarative reading would make the title into a complaint; his reading makes it into a lament. And because he was in the co-producer’s chair, you sense he knew exactly how close to place the vocal—near enough for intimacy, far enough to let the band answer back. Wikipedia

If you’re coming to the track fresh in 2025, the appeal is evergreen. This is grown-folk country, immune to fashions, resistant to the algorithm’s hunger for immediacy. It offers a study in adult ambiguity—how love can remain administratively intact while affection goes off the payroll. Part of the power is that the song doesn’t shout to be heard over the moment. It waits. It assumes you’ll find it when you need it.

“‘We Never Touch at All’ doesn’t beg for your tears; it asks you to recognize your own silence.”

For collectors and discography trackers, the cut’s placement on Chill Factor is instructive. That album gave Haggard one of his last big late-’80s victories and kept him in dialogue with a scene rapidly changing shape. Wikipedia As a single released in July 1988, written by Hank Cochran, it reaffirmed that quiet clarity could still chart in an era of brighter lights. Wikipedia I hesitate to pin an exact chart number here; what matters is the undeniable fact that the record found its audience, enough to register nationally and to keep Haggard’s voice on the air.

If you’re the kind who loves liner-note breadcrumbs, you might look up the album’s personnel and feel the continuity—the Strangers’ fingerprints are there, a band that had evolved with Haggard for decades. That historical through-line is audible: the interplay favors feel over flash, ensemble truth over individual heroics. It’s a reminder that a country singer isn’t just a voice; he’s a custodian of a sound and a set of choices that extend across rooms, years, and friendships. Wikipedia

And because music is also practical, two listening notes. First, try this song on a modest living-room system rather than a phone speaker; the low-volume bass and steal-away snare deserve air. If you’re an aspiring player, it’s a gentle study in space: the rests are as instructive as the notes. You won’t need a chart or “sheet music” to recognize the design, but you will need patience to play it right. And if you do most of your listening via a music streaming subscription, don’t be surprised if the algorithm starts handing you other, quieter Haggard cuts; treat that as a compliment to your taste.

We live in a moment of maximal confession—oversharing as proof of sincerity. “We Never Touch at All” moves the other way. It shares just enough to make a mirror without telling you what to see. That’s a moral choice as much as an artistic one, and it’s why the record keeps its weather even decades later. The song doesn’t promise repair. It promises recognition. Often, that’s the relief we’re secretly after.

In the end, the track stands as proof that subtlety isn’t a lack of courage. It’s a different expression of it. The narrative is spare, the playing is patient, and Haggard’s voice refuses to gild the bruise. That’s the kind of courage that ages well. Cue it up late, when the house has gone to sleep and the unresolved feels a little more resolvable. Let the last chord fade. Decide, gently, whether you’re ready to reach across the table again.