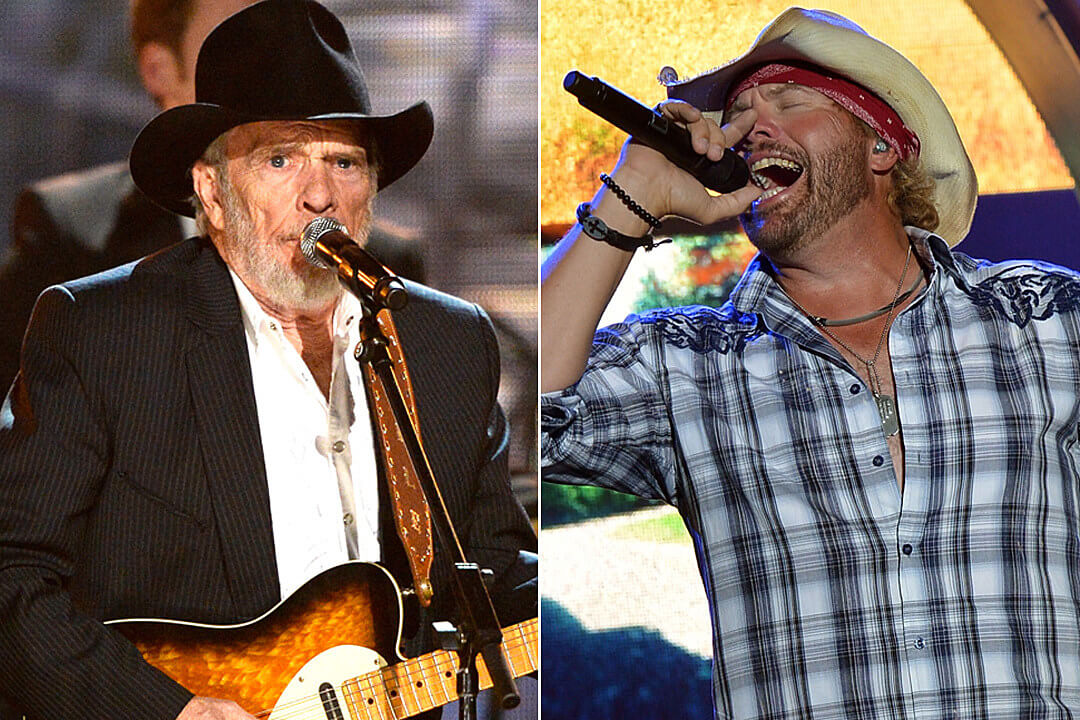

I first heard “The Fightin’ Side Of Me” the way many people do nowadays—late at night, not on a jukebox but on a thin laptop speaker that tried and failed to hold back the charge of a live crowd. The video was a grainy clip of Merle Haggard sharing the stage with Toby Keith, the two trading verses with a kind of easy respect that you can’t fake. The camera panned across faces—old ballcaps, leather jackets, couples mouthing the chorus—and you could feel the room tilting forward on every line. Even through compression artifacts and the flat glare of the screen, the music carried a stubborn pulse: the Bakersfield backbeat, the sting of telecaster, the voice of a man not apologizing for where he stands.

To review the song under the heading “Merle Haggard & Toby Keith – The Fightin’ Side Of Me” is to acknowledge two truths at once. First, “The Fightin’ Side Of Me” is Merle Haggard’s creation, released in 1970 on Capitol Records, produced by Ken Nelson, and accompanied by his band the Strangers. It topped the country charts and quickly became one of Haggard’s signature statements in the wake of “Okie from Muskogee.” Second, in the decades since, Toby Keith—an unabashed admirer of Haggard—has performed the song with him on stages and tribute broadcasts, giving the piece a second, parallel life. There isn’t one definitive studio single where both men share the microphone, but the duet has existed in multiple live settings, circulating in televised moments and concert recordings that fans pass around like postcards from a road still open.

Put the original record on—preferably through decent speakers—and you hear what made it rise. This is a lean, road-hardened arrangement that springs from the Bakersfield lineage Haggard helped codify: crisp drums set slightly forward, a walking bass that nudges the groove without showboating, and bright, wiry leads that slice like winter sunlight across a freeway. The rhythm section is stern but not stiff; it swings with short steps, letting the singer breathe between phrases. Where Nashville in the early ’70s often leaned toward strings and sweeteners, Haggard favored clarity—an audio window opened on a bar band so tight they could stop on a dime and give back change.

The guitar tone is dry enough to show fingerprints. There’s just a hint of room on the snare, a small halo that tells you the band stood in a real space, the kind of tracking room where the air itself becomes part of the rhythm. Steel lines curl around the melody like smoke, sometimes answering Haggard, sometimes pushing him into the next line. If a piano appears, it’s as a measured color rather than a lead instrument, tucked into the high end to spike the cadence of the chorus. Haggard’s vocal sits right where it belongs—center, unvarnished, with a steady vibrato that feels learned on the bandstand, not in a lesson. He phrases with the stubborn cadence of a man who knows exactly how much breath to spend on conviction.

Haggard’s songwriting in this period is often reduced to its headlines, but the tension lies in the details: the verses move briskly, balancing barbed observation with everyday cadence. The chorus, famously, stakes a claim. But the charge in the record is as much musical as ideological. Listen closely to the way the band lifts half a step into each refrain, the cymbals flashing a hair brighter, the steel punctuating like a raised brow. It’s the craft that keeps the message upright.

Now drop into one of those Merle-and-Toby performances. The arrangement remains essentially the same—why fix a chassis that still runs?—but the edges shift. Keith’s baritone thickens the blend, giving the lyric a different grain. He doesn’t imitate Haggard; he plants his boots and let his own phrasing do the work, rounding consonants, leaning into long vowels with a radio-seasoned ease. When they trade lines, what you hear is not just star power but lineage, a sense of the song moving from one pair of hands to another without losing the dings and burnish that make it valuable.

In some versions, you can feel the room pressing back. A cheer rises not at the end of a verse but mid-line, the telltale interruption of a crowd that knows where the stakes sit. The microphones catch the edges of that reaction; you hear it as a blush of reverb, a collective exhale that makes the band push tempo a fraction faster. Live, this piece of music gathers speed like a truck headed downhill—controlled, not reckless. The ending often lands with a dry stop, everybody cutting at once, letting the silence do the exclamation work.

Album context matters because it tells us where the song fits in a career arc. For Haggard, 1970 found him at a peak straddling commercial dominance and cultural debate. Capitol Records, with Ken Nelson’s steady hand, captured him as an artist who could move from gutsy dance-floor burners to reflective ballads without changing clothes. “The Fightin’ Side Of Me” also gave its name to a live album released that year, preserving his road show energy and tying the single to the heat of an audience. For Toby Keith, the song exists primarily in the orbit of homage; many sources note that he regularly cited Haggard as a lodestar, and their joint performances—particularly in the 2000s—play like a handshake across generations rather than a bid for reinvention.

The sound-world here is Bakersfield steel and Fender bite, not gilded Nashville plush. The drums sit with a dry, snappy top, more crack than boom. The bass favors clarity over sub-bass heft, a choice that keeps the two-step nimble. Electric fills are succinct, with a slightly overdriven edge that blossoms and then gets out of the way. There’s minimal studio trickery; compression is present to even dynamics, but the life of the performance survives. If you listen on good, closed-back studio headphones, the center image is firm, the cymbal decay quick like a light switched off in a motel room.

One of the sly pleasures of the record is how it balances public square and dance hall. The lyric lays out a position; the band makes sure you can still move to it. That dual purpose lets people pick their point of entry. Some arrive for the argument, others for the shuffle. Many stay for both.

Three short vignettes, because songs like this live in memories as much as in grooves:

A highway exit at dusk, somewhere between Amarillo and everywhere else. A trucker taps the steering wheel as the chorus comes around. The yellow lines strobe. He’s not thinking about politics. He’s thinking about how many miles he has left before the coffee goes cold.

A small-town VFW hall on a Friday night. A couple in their sixties stands up—not to make a scene, just to stand—when Haggard hits the hook on a live DVD playing on the mounted TV. Their grandson watches them, puzzled and a little moved, and later asks his dad why that song matters. The answer is a story about service, and disagreements at the dinner table, and why respect sometimes sounds like a guitar run instead of a speech.

A crowded arena, early 2000s. Toby Keith brings Haggard onstage and the place tilts. Phones go up; the sound gets bigger. When Keith steps back to let Merle take a verse, you see a smile that registers both fan and peer. It’s not about who sings it better. It’s about the handoff being witnessed.

We can argue endlessly about the cultural freight this song carries; that argument is older than most of us and will survive another round. What I hear today is the craft that makes the message travel. The form is pure, compact honky-tonk: verse, verse, chorus, solo, repeat. The solo is all economy—bends that say what they mean, no unnecessary trills. The singer’s breath lines match the bar lines with a precision that speaks to a thousand nights on stage. And in the best captures, you can hear the air in the room, that thin envelope between microphone and body where commitment lives.

It’s also a reminder that protest in country music can run both directions. Haggard wrote songs that questioned as often as they affirmed—“If We Make It Through December,” “Mama Tried,” “Sing Me Back Home”—and that complexity is part of why “The Fightin’ Side Of Me” resonates. Even listeners who bristle at the stance often acknowledge the force of the performance; even those who cheer the stance can admire the restraint of the arrangement. That duality is a feature, not a bug.

The duet dimension doesn’t overhaul the architecture; it adds weight-bearing beams. Keith tends to round the melody’s edges and push a touch more air through the vowels, while Haggard—especially in later years—sings with a weathered steadiness that cuts deeper than volume. The blend underscores the lyric’s communal posture: a single viewpoint voiced by more than one timbre. When the harmonies appear, they tend to be rough, human, the sort you get from singers who grew up in bars and radio stations, not conservatories.

Beneath the surface, you can hear how the recording’s dynamic choices carry the song. The verses sit a hair lower in intensity to set up the turn of the chorus. The solo lands right of center, bright but not ice-pick sharp, the pick attack audible, the sustain trimmed so the notes feel like spoken phrases rather than sermonizing. It’s classic country engineering: let the band be itself, and resist the temptation to coat the performance in sweet lacquer.

This is not a piece to over-theorize, but it is one to place carefully on the map. 1970 was a hinge year—Vietnam still burning, AM radio a battleground of slogans and hooks. Haggard’s single arrived as both a floor-filler and a flare; it worked because it moved. Decades later, when Keith called it up onstage with its author beside him, the song didn’t need an update. It needed sturdy hands.

If you come to the track as a musician, you’ll notice how cleanly it’s constructed. Chord-wise, we’re in familiar country territory; the pleasure is in the turns, the brisk walk to the dominant, the tidy recovery. Singers will note the way the melody rewards clarity of line over melisma. Players will clock how the fills leave emotional space. And if you’re the type who likes to study phrasing closely, you may find yourself looking for sheet music later just to map breath to bar, a quiet acknowledgment that the song’s skeleton is as sound as its skin.

“Songs like this don’t just stake a claim; they calibrate the room, and you can feel the temperature change when the first chorus lands.”

We’re used to treating songs with public arguments as artifacts locked to their moment. What keeps this one active is not unanimity but vitality. Some pieces shout; this one stands, sets its shoulders, and trusts its band. The result is oddly convivial: the record says exactly what it says, but it does so through sound that invites, a two-step open to anyone with the energy to move. You don’t have to agree to feel the downbeat hit and watch the dance floor fill.

A quick note for listeners stepping into Haggard’s catalog from the Keith side—or vice versa. The single is easy to find, and the live album from 1970 offers another angle, with crowd energy curling at the edges of each phrase. The duo performances show up in televised specials and concert footage—snapshots rather than a canonical release—but they serve their purpose. They make audible a lineage, not a merger.

There’s a reason artists keep returning to Haggard’s catalog: economy, empathy, and exactness of tone. Even when the subject is hard, the songcraft is generous. That’s what animates “The Fightin’ Side Of Me”—the fusion of conviction with craft, a rhythm section that never blinks, a vocal line that carries its weight without wobble. In the end, the takeaway is simple. Put it on, loud enough to feel the snare, and see if the room doesn’t rearrange itself around the groove.

If you’re upgrading your home listening chain, this cut will quickly reveal the difference between respectable and truly premium audio rigs, not because it’s flashy but because it relies on transient clarity and center-image stability. Play it once in a quiet room; then take it into daylight, on a drive, and notice how its momentum survives the highway hum. Switch singers if you like—Merle solo, a live clip with Keith—watch the shape hold.

One last observation: the durability of “The Fightin’ Side Of Me” has less to do with an era’s headlines than with a bandleader’s belief in timing. The measure of the record is how it sits in the pocket, how the fills know when to speak and when to hush, how the voice trusts the line. As long as that grammar survives—swing, sting, statement—the song will walk into new rooms and find its footing.

So cue it up again. Let the opening bars reassert their balance of steel and snap. Listen for the breath before the first line, the human pause that turns a statement into a performance. And if you’re hearing it in a room with someone you love, watch for the small instinctual movements—the foot keeping time, the nod on the downbeat—that tell you the song has done what it came to do.

Listening Recommendations

-

Merle Haggard – Okie from Muskogee — Adjacent era and stance; live-wire Bakersfield band cutting a cultural line with dance-floor muscle.

-

Merle Haggard – Are the Good Times Really Over — A later, reflective counterweight; same writer, different weather, steel guitar sighs.

-

Toby Keith – Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American) — Modern-era protest energy with a heavier backline and arena-sized chorus.

-

Johnny Cash – Ragged Old Flag — Spoken-word patriot’s prayer; spare arrangement, moral center foregrounded.

-

Waylon Jennings – Lonesome, On’ry and Mean — Outlaw grit and telecaster roll; similar no-frills mix that prizes feel over gloss.

-

Alan Jackson – Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning) — A calmer, contemplative response from the same broad tradition of national reflection.