The air in 1969 was thick with change, heavy with the scent of incense and tear gas. It crackled with the energy of protest and the low hum of generational anxiety. From radios across America, the sounds of psychedelia, soul, and acid rock tumbled out, scoring a decade of upheaval. Then, through the static, came a different sound. A sound as clean and sharp as a fresh razor cut, carried by a voice that was anything but confused.

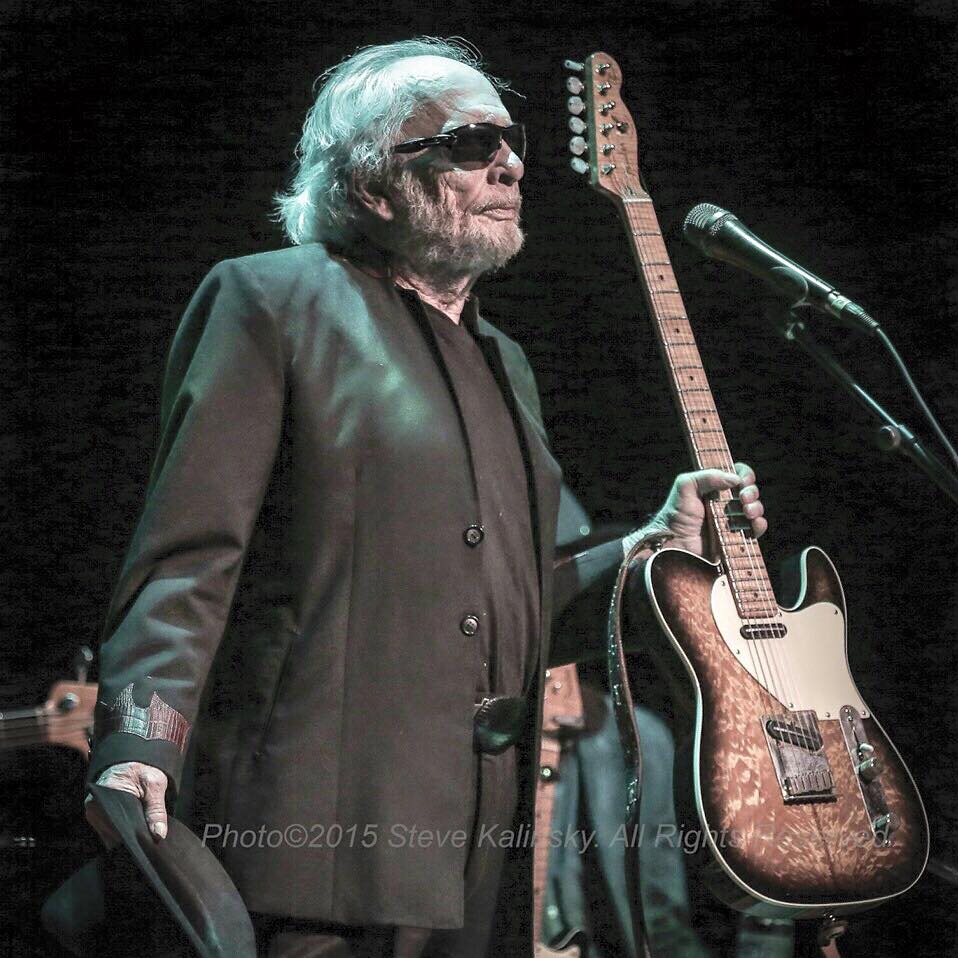

It was the sound of a Fender Telecaster, its notes bent and whining. It was the sound of a walking bassline, steady as a heartbeat. And it was the voice of Merle Haggard, calmly declaring his pride in a place where they “still wave Old Glory down at the courthouse.” The song was “Okie from Muskogee,” and it didn’t just capture a sentiment; it drew a battle line in the dust of the American cultural landscape.

To understand this song, you must first hear it as it was intended to be heard: live. The definitive version wasn’t a sterile studio creation but the title track from the 1969 live album, Okie from Muskogee, recorded in front of a roaring, adoring crowd in that very Oklahoma city. The roar is part of the instrumentation. It’s the sound of validation, a great, collective sigh of relief from a segment of the population that felt mocked, ignored, and left behind by the cultural revolution.

Produced by the legendary Ken Nelson for Capitol Records, the recording is a masterclass in Bakersfield grit. The Strangers, Haggard’s airtight backing band, operate with locomotive precision. Roy Nichols’s guitar work is the star—not with flashy solos, but with stinging, economic fills that punctuate Haggard’s deadpan delivery. There is no sentimentality, no string section to soften the edges. This is lean, muscular country music, built for dance halls and jukeboxes, not for contemplative afternoons.

The sound is immediate and present. Listening on a quality home audio system today, you can almost feel the heat from the stage lights. The mix is clear and unadorned, placing Haggard’s resonant baritone front and center, with the pedal steel crying in one channel and the electric guitar answering in the other. It’s a document of a moment, raw and unfiltered.

Merle Haggard was perhaps the only person who could have written and delivered this song with any semblance of authenticity. By 1969, he was already an established country superstar, the poet of the common man, but his backstory gave his words an unassailable gravity. He wasn’t some Nashville suit playing a role; he was a real-life Okie, the son of Dust Bowl migrants. He was a high school dropout, a freight-train hopper, and a former inmate of San Quentin prison who saw Johnny Cash perform there.

His past lent a profound irony to the straight-arrow narrator of “Okie.” Here was a man who had flagrantly disrespected the law, who had lived a life far from the clean-cut image he was now championing. This wasn’t hypocrisy; it was complexity. Haggard wasn’t singing as himself, necessarily. He was creating a character, a vessel for the anxieties and resentments of what President Nixon would soon christen the “silent majority.”

“We don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee; we don’t take our trips on LSD.” The lines are simple, direct, a point-by-point refutation of counterculture stereotypes. “We don’t burn our draft cards on Main Street; we like livin’ right, and being free.” For millions of Americans, these weren’t just lyrics; they were a creed. They were the words they felt but couldn’t articulate, a defense against a world they no longer recognized.

Imagine a trucker, somewhere on I-40 late at night, the radio his only companion. For hours, he’s heard songs about free love and revolution that feel alien, broadcast from a different planet. Then comes that clean guitar intro, that steady voice. He hears his own frustrations, his own simple pride, reflected back at him. He turns the volume up. He feels seen.

Now imagine a college student in a Berkeley dorm room, arguing with friends. To them, the song is a joke, a simplistic, jingoistic caricature. It’s everything they are fighting against: conformity, blind patriotism, intolerance. Yet, they can’t get it out of their heads. The melody is too good, the conviction too real. It’s a piece of music that forces you to take a side, even if that side is against it.

“The song’s power lies not in what it says, but in the fault lines it exposes.”

Over the years, Haggard himself gave conflicting accounts of the song’s genesis. Sometimes he claimed it was a sincere expression of his feelings while watching war protesters on television. Other times, he suggested it was a tongue-in-cheek satire, an exaggeration of a small-town mindset, born on a tour bus as a joke between him and his drummer. The truth, most likely, lives somewhere in the ambiguous space between the two.

What is undeniable is its musical effectiveness. The arrangement is deceptively simple. Unlike the syrupy Nashville Sound of the era, there is no weeping piano to guide the emotion. The rhythm section provides a sturdy, no-nonsense foundation, leaving space for the instrumental voices to speak. The crisp attack of the lead guitar became so iconic that countless young players sought out guitar lessons hoping to capture even a fraction of that Bakersfield twang. The whole thing is over and done in under three minutes, a perfectly constructed musical statement.

The song became Haggard’s biggest hit and his signature tune, for better or worse. It cemented his image as a conservative icon, a label he would spend the rest of his career complicating with songs that showed deep empathy for the downtrodden, the outcast, and the working poor. The same man who sang “Okie” would later sing “Irma Jackson,” a powerful song about interracial love, and “Are the Good Times Really Over (I Wish a Buck Was Still Silver),” a lament for a lost America that felt more mournful than celebratory.

The full live album from which the single was pulled is essential listening. It shows the song in its element, surrounded by other Haggard classics that paint a fuller picture of the artist. It’s a snapshot of a master performer connecting with his audience on an almost cellular level.

To listen to “Okie from Muskogee” today is to open a time capsule. The specific cultural references might feel dated, but the underlying tension is timeless. It’s the tension between the city and the country, between tradition and progress, between a national myth and a messier reality. It’s a song that asks a fundamental question: What does it mean to be an American?

Forget, for a moment, the politics and the half-century of baggage. Just listen. Listen to the confidence in that voice, the coiled energy of the band, the roar of that crowd. You are hearing more than a hit song. You are hearing the sound of a culture defining itself, one defiant verse at a time.

Listening Recommendations

- Johnny Cash – “The Man in Black”: A similarly stark, first-person declaration of identity and allegiance with the underdog.

- Loretta Lynn – “Coal Miner’s Daughter”: An autobiographical anthem of rural pride and working-class dignity, delivered with unshakeable honesty.

- Buck Owens and The Buckaroos – “Act Naturally”: The other pillar of the Bakersfield sound, showcasing the same tight, trebly, no-frills instrumentation.

- Guy Clark – “Desperados Waiting for a Train”: Offers a more nuanced, character-driven portrait of an “Okie” figure from a different, more literary perspective.

- Sturgill Simpson – “Turtles All the Way Down”: A modern example of a country artist tackling heady social themes (drugs, religion) with a sound rooted in tradition.

- Waylon Jennings – “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way”: A critique of the Nashville establishment that shares Haggard’s outlaw spirit and demand for authenticity.

Video

Lyrics

We don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee

We don’t take no trips on LSD

We don’t burn our draft cards down on Main Street

We like livin’ right, and bein’ free

We don’t make no party out of lovin’

We like holdin’ hands and pitchin’ woo

We don’t let our hair grow long and shaggy

Like the hippies out in San Francisco do

And I’m proud to be an Okie from Muskogee

A place where even squares can have a ball

We still wave Old Glory down at the courthouse

And white lightnin’s still the biggest thrill of all

Leather boots are still in style for manly footwear

Beads and Roman sandals won’t be seen

Football’s still the roughest thing on campus

And the kids here still respect the college dean

And I’m proud to be an Okie from Muskogee

A place where even squares can have a ball

We still wave Old Glory down at the courthouse

And white lightnin’s still the biggest thrill of all

In Muskogee, Oklahoma, USA