Table of Contents

ToggleThere are songs that entertain, songs that top charts, and then there are songs that seem to arrive from somewhere older than radio itself—stories carried on desert winds and whispered through motel windows at midnight. “Pancho and Lefty” belongs to that rare final category. Written by the enigmatic Texas troubadour Townes Van Zandt, the song has grown from a quiet folk lament into one of the most revered outlaw ballads in modern music history.

It is not merely a tale of two men. It is a meditation on loyalty, betrayal, survival, and the unbearable weight of growing old.

A Song Born in Obscurity

When Van Zandt released “Pancho and Lefty” in 1972 on his album The Late Great Townes Van Zandt, there was little fanfare. No chart placements. No radio push. No glittering promotional campaign. The album drifted quietly into the hands of devoted folk listeners, largely unnoticed by the mainstream.

That obscurity feels almost poetic in hindsight.

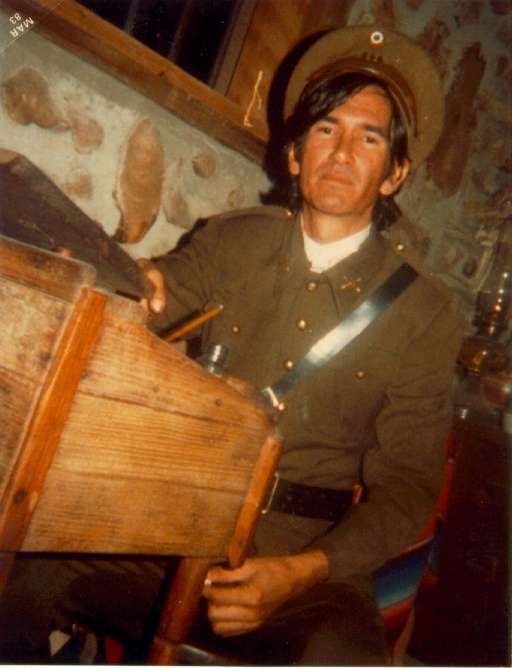

Van Zandt himself was a figure shrouded in contradiction—a songwriter’s songwriter, deeply respected by peers yet commercially overlooked. His life was marked by brilliance and turbulence, a restless spirit wandering through Texas honky-tonks and lonely highways. In many ways, “Pancho and Lefty” mirrors its creator: spare, mysterious, and unconcerned with commercial ambition.

The original recording is stark. Just Van Zandt’s soft, weary voice and a restrained acoustic guitar. There is no dramatic orchestration, no cinematic swell—only the slow unfolding of a story that feels both intimate and mythic.

The Song That “Drifted Through the Window”

The legend surrounding the song’s creation is almost as captivating as the lyrics themselves. Van Zandt once claimed he wrote it in a cheap hotel room near Denton, Texas, after being forced out of better lodging by a large Billy Graham crusade event that had filled the town. Sitting alone in a modest room, he said the song simply “drifted through the window.”

When asked by Willie Nelson what the song meant, Van Zandt reportedly shrugged and said, “I don’t know.”

That ambiguity is not a flaw—it is the song’s secret strength.

Some speculate that Pancho is a symbolic outlaw, perhaps inspired loosely by Mexican revolutionary figures like Pancho Villa, while Lefty represents the quieter companion, the survivor who trades loyalty for life. Others believe the names were drawn from two police officers Van Zandt once encountered—nicknamed “Pancho and Lefty”—one Anglo, one Hispanic.

But the truth remains intentionally elusive. And that mystery allows every listener to project their own meaning onto the story.

A Compact Novel in Four Minutes

Lyrically, “Pancho and Lefty” reads like a condensed Western novel.

Pancho, the charismatic outlaw, meets a lonely death “down in Mexico.” The poets romanticize his fall. Songs are sung. Legends are written. He becomes immortal in the way fallen rebels often do.

Lefty, however, survives.

And survival, Van Zandt suggests, is not always heroic.

“The day they laid poor Pancho low,

Lefty split for Ohio.

Where he got the bread to go,

There ain’t nobody knows.”

It is one of the most devastating verses in American songwriting. In just a handful of lines, Van Zandt sketches an entire moral dilemma. Did Lefty betray Pancho for money? Did he simply do what he had to do? Was it cowardice—or necessity?

The genius lies in what is left unsaid.

Pancho dies young, forever frozen in the golden haze of legend. Lefty grows old in cheap hotels, carrying the invisible burden of compromise. In the final lines, Van Zandt offers a surprising tenderness toward both men:

“He only did what he had to do,

And now he’s growing old.”

There is no condemnation. No moral judgment. Only recognition.

From Cult Classic to Chart-Topping Hit

More than a decade after its quiet release, “Pancho and Lefty” found a second life—one that would elevate it into country music history.

In 1983, Willie Nelson joined forces with Merle Haggard to record the song as the title track of their collaborative album Pancho & Lefty. The duet transformed the song from hushed folk poetry into a mainstream country triumph.

Their version soared to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart and dominated Canadian country charts as well. With polished early-’80s production, warm harmonies, and the unmistakable voices of two legends, the song reached millions who had never heard Van Zandt’s original recording.

For Van Zandt, the success finally brought substantial royalties—though by most accounts, he remained characteristically detached from its commercial impact.

It is one of music history’s bittersweet ironies: the songwriter whose pen created the legend only tasted widespread recognition after others carried it into the spotlight.

Why It Still Resonates

More than fifty years after its birth, “Pancho and Lefty” continues to captivate new generations. Why?

Because its themes are universal.

Youth often dreams of rebellion, glory, and fearless loyalty. But adulthood introduces compromise. Responsibilities. Quiet decisions made in the name of survival. Pancho represents the romantic ideal—the daring spirit who burns bright and dies young. Lefty represents the path most of us take: living longer, perhaps safer, but carrying unanswered questions.

For older listeners especially, the song strikes deep. It speaks to roads not taken, friendships strained by time, and the subtle ache of realizing that survival sometimes demands painful trade-offs.

It is an elegy not just for an outlaw—but for lost innocence.

A Legacy Beyond Charts

Today, “Pancho and Lefty” is widely regarded as Townes Van Zandt’s masterpiece. It has been covered by numerous artists, studied by songwriters, and cited as a pinnacle of narrative songwriting. Its power lies not in elaborate production or dramatic hooks, but in restraint.

Few songs manage to feel this intimate and this epic at the same time.

It stands as proof that great songwriting does not shout. It lingers. It haunts. It waits patiently for listeners to catch up.

And perhaps that is the ultimate irony: the song that once slipped quietly into the world from a lonely motel room now echoes across decades, its desert winds still carrying the names Pancho and Lefty.

In the end, the question remains unresolved: Was Lefty a traitor—or simply a man trying to live?

Van Zandt never answered.

He didn’t have to.