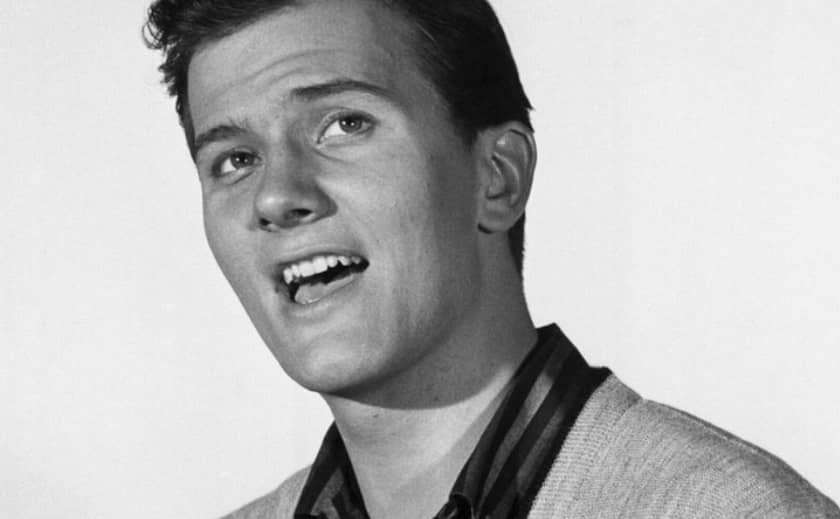

Pat Boone didn’t need tape hiss to make an entrance in 1962. He had a grin you could hear and a microphone presence that made even the fizziest joke play like a promise. Drop the needle on “Speedy Gonzales,” and you’re greeted by a tableau that arrives already lit: moonlight over some imagined border town, a chorus of teasing voices, a door flung open on a party you weren’t sure you should crash. Pat ushers you in anyway. Suddenly, a voice you know from Saturday mornings zips through the speakers, and you realize this single isn’t just a novelty—it’s a small theater piece, a comic postcard glued into the pop scrapbook of its day. The record wasted no time becoming a hit in 1962, reaching the U.S. Top 10 and surging across several European charts. Wikipedia

“Speedy Gonzales” began life a year earlier, recorded by David Dante (David Hess), with song credits to Buddy Kaye, Ethel Lee, and Dante/Hess. Boone’s version is the one most listeners remember, partly because it tightens the dramaturgy and adds instantly recognizable cartoon interjections by Mel Blanc, the original voice of Speedy. Those cameos are more than a gag—they’re structural hinges that break the song into comic vignettes and keep the groove skipping forward. The effect is light as confetti yet weirdly architectural, like a radio play hiding inside a two-and-a-half-minute jukebox spin. Wikipedia

Let’s fix the historical frame. Boone released “Speedy Gonzales” as a Dot Records single in 1962, with credits that place the project in the hands of Dot founder Randy Wood, and with conductor/arranger Jimmie Haskell guiding the ensemble. Multiple discographies and label listings place it in May of that year; it later appeared on a compilation titled “Pat Boone’s Golden Hits Featuring Speedy Gonzales,” issued in 1962 as a way to corral his era-defining smashes. For orientation: Boone had already logged seven years of chart presence by then—clean-cut, white-bucks cool, an ambassador of gentler rock ’n’ roll inflections. The single, in other words, arrives during his mature commercial phase; it’s not a breakout, it’s a reaffirmation of reach. YouTube+3secondhandsongs.com+3Wikipedia+3

Because novelty is a high-wire act, the arrangement matters. Haskell’s charts on early ’60s pop tended to carry a brisk, sunlit clarity, and that’s what you hear here: bright brass figures that punctuate lines like exclamation marks; a rhythm section walking with a dancer’s heel-toe confidence; and a chorus that glides in and out like party guests leaning over the banister to shout friendly advice. Listen to the stereo image on modern transfers: the voices are stacked so their edges never blur, leaving room for the comic drop-ins. The handclaps feel close; the percussion has a dry room character, as if dampened to keep splash out of the vocal mic. Boone sings with an earnest twinkle—largely straight-faced, which is key. Comedy lands when the singer refuses to wink too hard.

There’s folklore attached to the voices. The female “la-la-la” lines often get credited to Robin Ward, a singer who did a good deal of session work in that period. Combined with Blanc’s speedy interjections, they create counter-characters who nudge the narrative forward—one coaxing and melodic, one mischievous and manic. The record’s most famous line readings snap into place like jump cuts, and the whole thing rides the tension between Boone’s croon and Blanc’s cartoon patter. That contrast—crooner poise versus animated chaos—is the single’s signature texture. Wikipedia

What keeps “Speedy Gonzales” interesting more than sixty years later is how it manages the tropes of its time. This is a postcard of “south of the border” fantasy, filtered through early-’60s mainstream pop. The guitars and brass sketch stylized fiesta colors; the call-and-response makes it feel communal; and the lyric, in Boone’s revision, frames the story as an overheard plea to tame a wayward romancer. A novelty, yes—but also a miniature about competing tempos: the party’s breathless sprint versus the lover’s steady insistence. On radios built for daytime brightness, the record must have glittered like crushed sugar.

Melodically, the tune pivots on an easy rise-and-fall that lets Boone lean into rounded vowels and clipped consonants. He shapes phrases with a showman’s diction, clipping the ends just enough to leave room for Blanc’s drop-ins. The rhythmic ideas are simple and effective—syncopated stabs that keep your shoulders moving, little gallops in the drum pattern that mimic the character’s dash. This piece of music is engineered for quick delight: a set-up, a call, a comic interruption, a chorus that returns like a friendly echo. Its dynamics are mostly medium-bright, but they breathe; when the chorus pulls back, you can hear the band reset, sunlight through leaves.

Production credits matter for pop archaeology. Dot Records, with Randy Wood at the helm, specialized in clean, accessible sonics—radio-first mixes where the lead vocal sat high and dry, never smothered by reverb. On “Speedy Gonzales,” that approach keeps the narrative clear and the interjections intelligible. Haskell’s conducting reportedly keeps the ensemble tidy, especially the brass, whose entrances are crisp without the blare that plagued some contemporary pressings. On vinyl, sibilants can skate, but this cut tends to hold them in lane. In other words, the decisions were commercial but craft-aware. YouTube

A few data points round out the story. Contemporary sources and chart archives note that Boone’s version climbed into the U.S. Top 10 and had even greater success in parts of Europe. The record’s cultural footprint includes one of those industry anecdotes that makes lawyers twitch: a reported suit from Warner Bros. over the use of Speedy’s voice, later dropped. That dust-up, however brief, tells you how ubiquitous the record became—big enough for a studio to notice, and quick enough on the air to seem inevitable. Wikipedia

Now, to the sound in the room. Imagine the arrangement stripped to its bones. A rhythm section walking in silhouette. A bright, slightly nasal brass choir leaning on upper harmonics for lift. A backing vocal line that behaves like set dressing—curtains fluttering, lights warming. Then layer in the comic voice-overs, which function like stage whispers that the audience can hear but the protagonist cannot. The trick is staging: Boone keeps singing to the front rows while the jokes happen in the wings. When the chorus arrives, everyone faces the audience and the room widens again.

I keep returning to the image of a traveling fair—bright colors, zippers on the rides, sticky soda caps underfoot. That’s the energy “Speedy Gonzales” captures. And yet, within the carnival, Boone’s tone remains courtly, even gentle. His phrasing refuses to snarl. That restraint is the record’s ballast and the reason it hasn’t curdled with time. Where some novelties rely on mockery, this one opts for cheerful bustle, a pageant where nobody gets hurt and every punchline wears confetti.

Two short vignettes come to mind. The first: late-night radio in a kitchen lit by one stubborn bulb, summer heat pressing against the window. The song pops up, and your grandfather—who rarely hums—taps the table with a knuckle, then half-smiles when the cartoon voice rings out. He’s not remembering 1962 exactly; he’s remembering a mood, a world where a three-minute record could feel like a street party summoned from thin air. The second: a kid on a backseat road trip, fingers drumming on vinyl upholstery while the chorus “la-la-la” trails across the windshield. For that kid, novelty isn’t a gimmick; it’s sonic confetti keeping boredom at bay. The memory sticks.

Let’s also be clear about context. Boone wasn’t remaking youth culture with this track; he was updating his relevance amid a shifting pop landscape. By ’62, rock ’n’ roll had matured into multiple dialects: girl groups with sophisticated arranging, surf instrumentals, soul records with church in the bones. Boone’s single fits into the novelty wing, but it borrows arrangement polish from pop proper—tight horn voicings, backing vocals that move like a string section would, rhythm parts engineered to sit comfortably in jukebox cafes. It’s halfway between a comic sketch and a well-appointed showroom number.

One reason the record endures is its efficient imagery. The lyric foregrounds familiar icons—adobe walls, a cantina glow, the moon as stage light. Musically, the arrangement mirrors that iconography with percussive flourishes that flicker like lanterns. The balance between voice and band is particularly neat. When the cartoon crumb of dialogue appears, the band dips, then springs back. It’s a lesson in arranging negative space: don’t just stack; carve.

Here is where I address the musician’s ear. Listen to how the bass locks with the kick, and how the tambourine (or high percussion equivalent) is rationed—never a constant jingle, more like a prompt to lift the chorus. Note the bright, slightly percussive keyboard comping that behaves like a stand-in for a brittle upright; you can imagine a piano on the session shading the groove with clipped chords. Guitar fills are brief, decorative—ribbons tied to the phrase endings—and they retreat the moment the vocal needs air. The entire mix is a study in second-row upholstery: everything supportive, nothing lumpy.

“Speedy Gonzales” also embodies the friction between glamour and grit that defined much early-’60s pop. Glamour: the sheen on Boone’s vocal and the immaculate balance that Dot’s producers favored. Grit: the lived-in texture of novelty itself—jokes that wear out their soles on the dance floor, a joyous silliness that refuses to apologize. That friction is what makes the record feel tactile rather than slick.

“Novelty records age best when they hide a little craftsmanship in the confetti—and ‘Speedy Gonzales’ hides more than a little.”

The release history adds a final panel to the triptych. Issued as a single on Dot Records, the track was compiled later that year on “Pat Boone’s Golden Hits Featuring Speedy Gonzales,” a package that functioned as a snapshot of Boone’s durable chart persona. Compilation placement like that usually signals two things: immediate commercial impact and a bet that the song would have catalog life. It did; reissues and digital listings keep it in circulation, and radio programming for “oldies weekends” continues to treat it as a recognizable spark. Wikipedia+1

For listeners encountering it now, perhaps via a curated playlist, the record sits at an interesting cultural angle. Its cartoon borrowing, its caricature vocabulary, and its postcard Mexico all reflect 1962’s mainstream lens. Approaching it today invites a double listen: one ear for the craft and effervescence, one ear aware of how representation has evolved. If you hold both frames at once—craft and context—the record offers more than nostalgia. You hear how a mainstream pop machine made room for comedy without sacrificing musical order.

Curators and collectors will care about credits, so they’re worth restating with cautious clarity. The single traces to Dot, with Randy Wood named as producer on contemporary digital credits and Jimmie Haskell noted as conductor of the session. It’s also widely noted that Mel Blanc voices the titular interjections; that detail enters the song’s lore along with the brief legal kerfuffle that reportedly followed. Boone’s chart performance: top tier in the U.S. for the season and prominent in several European markets. Exact placements vary by source, but the consensus places it firmly among the year’s earworms. YouTube+1

What to do with the song now? Try it on a good pair of studio headphones once, and you’ll notice how carefully the comic inserts have been slotted into the stereo picture on remasters. Then play it in a room with friends; it performs better as a communal artifact than as a private grin. If you’re a musician, glance at the available sheet music and you’ll see how the melody’s range and the rhythmic profile invite a light touch rather than vocal fireworks. Keep it bouncy, keep it clean, and the laughter will land.

As you revisit Boone’s catalogue around this period, “Speedy Gonzales” resembles a marker flag when the winds were changing. British beat would soon pour over the airwaves, soul was gathering new voltage, and novelty as a chart mainstay would crest and then thin. Yet this single, buoyant as a paper lantern, reminds you that the early ’60s pop factory could still turn out pieces that sparkled without strain. It’s a comic mini-play with a tight orchestra pit, and it still moves.

Final perspective. If this were just a gag, we would have forgotten it. But the rhythm still hops, the voices still tag-team the scene, and the whole thing reaches the ear like a postcard from a livelier, tidier radio age. The next time it sneaks into your day, don’t swat it away. Let it run its course, grin at the cameo, and hear the care tucked inside the confetti. If you listen for the frame—the arranging hands, the label polish, the mix that bends around the jokes—you may find yourself queueing it up again, not for the punchline, but for the craft that made it land.

Listening Recommendations

-

Ritchie Valens – “La Bamba” — Folk-rock rhythm and party-circle vocals delivering a timeless dance-floor lift.

-

The Coasters – “Yakety Yak” — Comedy woven into immaculate R&B arrangement; punchy horns and crisp call-and-response.

-

Paul Anka – “Eso Beso (That Kiss!)” — Early-’60s Latin-tinted pop with suave phrasing and a bright, ballroom glide.

-

Ray Stevens – “Ahab the Arab” — 1962 novelty with narrative voice-overs and a tightly marshaled band groove.

-

The Champs – “Tequila” — Instrumental exuberance and fiesta color from sax and rhythm section, perfect adjacent mood.

YouTube+4Wikipedia+4secondhandsongs.com+4