It is a quiet, late afternoon memory, washed in the amber glow of a pre-digital era. The old stereo, a hulking teak console, dominates the corner of a room, and the air crackles with the slightly compressed, undeniably warm fidelity of a classic Capitol 45. I remember hearing this piece of music for the first time—the simple, almost hesitant piano motif that opens Peter & Gordon’s 1966 single, “Woman.” It was, and remains, an exercise in sonic misdirection, a soft-spoken giant in the crowded soundscape of the British Invasion.

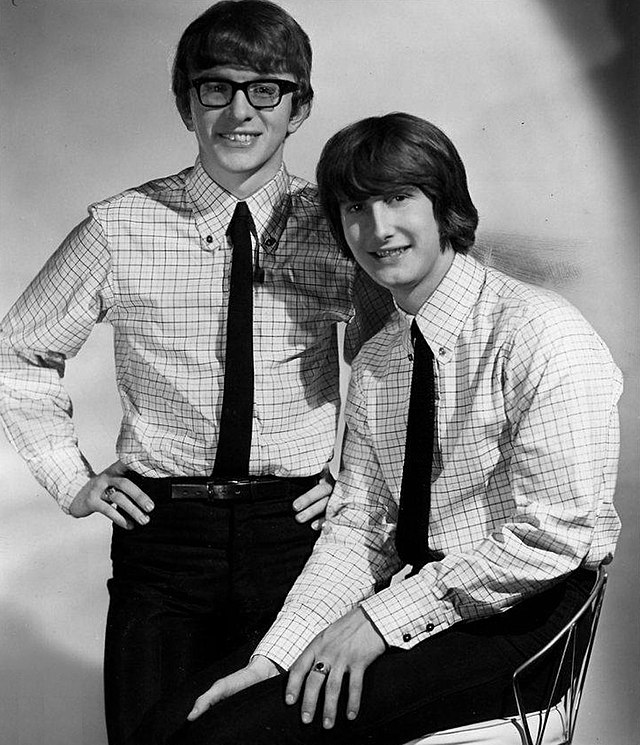

The true story of “Woman” is music lore of the highest order. Peter Asher and Gordon Waller were already successful protégés of the Lennon-McCartney songwriting machine, having hit big with the duo’s first three singles handed to them by the Beatles’ star composers. Yet, an undercurrent of skepticism persisted in the press: were Peter & Gordon merely riding the coattails of their more famous friends? Paul McCartney, who was dating Peter’s sister Jane Asher at the time and was living in the Asher family home, was reportedly irked by the insinuation.

McCartney decided to conduct a covert experiment. He penned “Woman,” a beautiful, plaintive song, and credited it to an entirely fabricated writer: one Bernard Webb, supposedly a French student and a man unavailable for interviews. This was a direct challenge, a way to test if the composition could succeed based solely on its own merit, stripped of the marketing power of the world’s most famous songwriting credit. While the publishing was still controlled by Northern Songs, the deception held for a glorious, fleeting two weeks before an astute critic or industry insider—or simply the inherent quality of the song—forced the truth into the open.

The Sound of Deception and Sophistication

The arrangement of “Woman,” produced by John Burgess, is a masterclass in the era’s pop sophistication, revealing why Gordon Waller would later cite it as his personal favorite in the Peter & Gordon catalogue. It exists outside the standard rock-band paradigm. There is a clean, slightly cavernous drum sound that anchors the mid-tempo rhythm, but the true texture comes from the interplay between acoustic instruments and the gentle, almost heartbreaking swell of the orchestra.

The introductory piano—a brief, descending arpeggio—sets a melancholy, reflective mood before the twin voices of Peter and Gordon enter. Their signature harmonies, clear, precise, and emotionally restrained, are the core of the record. They deliver the lyric’s central question, “Woman, do you love me? Woman, if you need me then,” with a vulnerability that is almost jarring for a pop single of the time. The vocal mic technique here feels relatively close, perhaps a pair of Neumanns capturing the intimacy, with a slight, beautiful air around them, suggesting a spacious recording room.

As the verse develops, the simple rhythm section is elevated by the appearance of the string section. These aren’t the dramatic, sweeping strings of a Broadway score; they are a discreet, almost baroque-like counterpoint, weaving a complex emotional tapestry behind the vocals. This use of strings, carefully placed for texture rather than bombast, shows an emerging maturity in pop production. One can appreciate the careful balance required to present this classic recording on premium audio equipment, allowing the subtle shifts in orchestration to be heard clearly.

The guitar work, too, is understated but essential. A clean, chimey electric guitar provides simple, high-register embellishments and fills, adding a metallic gloss to the primarily acoustic landscape. It avoids the blues-rock swagger of their peers, opting instead for a delicate, melodic function, supporting the vocal line. This restrained instrumentation speaks volumes, proving that a song doesn’t need volume or fuzz to be powerful. It just needs structure, melody, and a genuine emotional hook.

“Woman” was released as a standalone single in January 1966 in the US, and a month later in the UK. It was not originally attached to a formal studio album; rather, it punctuated a prolific period for the duo, standing as a testament to their ability to inhabit a song and make it sound completely their own. Its chart performance was solid but not explosive, reaching as high as No. 14 in the US and No. 28 in the UK. But its deeper legacy lies in the experiment itself. It was a successful test case: the melody and structure were undeniable, even without the famed songwriting pedigree openly attached.

“The greatest pop compositions often exist in that sweet spot where simplicity of sentiment meets complexity of structure.”

A Subtle Power and Enduring Resonance

I often recommend this track to aspiring musicians who are convinced that modern pop requires endless layers of production. The lesson of “Woman” is restraint. Listen to the way the dynamics shift in the chorus; the collective energy lifts, but never spills over. The arrangement feels like a tightly-coiled spring, providing tension and release without ever fully unleashing a catharsis. This disciplined approach is a hallmark of the best British pop of the mid-60s.

When I listen to it now, sometimes I imagine the moment Paul McCartney casually played a rough version of the guitar chords for Peter Asher in the Asher family’s Wimpole Street home. Perhaps it was scribbled on some makeshift sheet music. That moment, that casual creative generosity, launched a transatlantic hit and cemented the duo’s reputation as interpreters of the highest calibre. They were not simply singing Paul’s songs; they were embodying them.

The song’s micro-stories continue today. I know a couple who chose it as their first dance, the uncomplicated declaration of loyalty resonating deeper than any overwrought ballad. I also know a songwriter who studied the descending bass line and the subtle harmonic movement as a blueprint for elegant, melodic transitions. It is a deceptively powerful three minutes, a demonstration of how a sophisticated chord sequence can elevate a common-denominator lyric into something profound.

“Woman” stands as a gentle giant—a song designed to prove a point about authorship, but which ultimately proved a more enduring truth about the universality of melody. It is a vital chapter in the Peter & Gordon story, a bridge between their early, chart-topping fame and the slightly more experimental phase that would follow. Give it a deep, attentive listen; you’ll find layers of sonic brilliance beneath the friendly pop exterior.

Listening Recommendations

- Chad & Jeremy – “A Summer Song” (1964): Shares the same polite, acoustically-driven British duo charm and wistful string arrangements.

- The Association – “Never My Love” (1967): Features similarly lush, orchestral pop production and seamless, layered vocal harmonies.

- The Zombies – “Say You Don’t Mind” (1968): A beautiful, emotionally rich track with delicate piano and sophisticated, slightly melancholic melodic progression.

- The Beatles – “Yesterday” (1965): Another McCartney composition relying on stark acoustic guitar and strings to convey profound vulnerability and reflection.

- The Walker Brothers – “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” (1966): Excellent example of dramatic, heavily orchestrated ’60s pop, showing the grandiose side of the era’s sophisticated arrangements.

- Herman’s Hermits – “There’s a Kind of Hush” (1967): Embodies the softer, melodic end of the British Invasion, focused on gentle piano and heartfelt, direct vocals.