The air in mid-80s Nashville was thick with gloss. Synthesizers, gated reverb on the snare drums, and a pop-crossover sheen had become the uniform of country radio. The raw, gritty soul of Haggard and Jones felt like a distant echo, a relic from a bygone era. The Urban Cowboy had ridden off, but he’d left his sequined jacket hanging in every recording studio on Music Row.

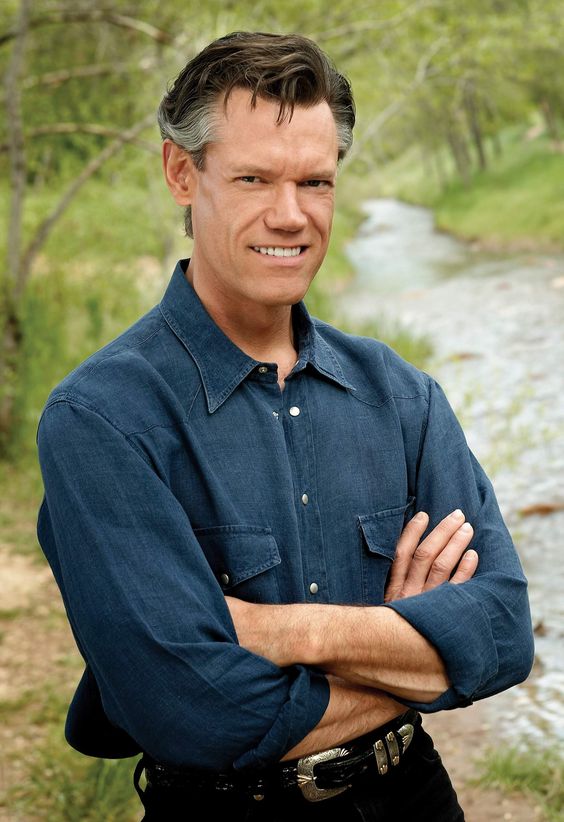

Then, a sound cut through the noise. It wasn’t a shout; it was a murmur, a low, steady baritone that felt less like a performance and more like a confession. It arrived on a current of clean, weeping steel guitar and the simple, honest strum of an acoustic. That sound was Randy Travis, and the song was “On The Other Hand.”

Released initially in 1985 to a lukewarm reception, the song was a commercial anomaly. It was too spare, too traditional, too country for the moment. But persistence, and the success of his follow-up single “1982,” gave Warner Bros. the confidence to re-release it a year later. This time, it didn’t just chart; it detonated a quiet bomb, signaling the arrival of the “neotraditionalist” movement and crowning its first king.

The song, penned by the legendary duo of Paul Overstreet and Don Schlitz, is a masterwork of lyrical tension. It’s a simple premise: a man sits in a bar, tempted by a new woman, weighing his fleeting desires against his solemn vows. The genius is in its central metaphor, a device so elegant and obvious you can’t believe it hadn’t been the hook for a hundred songs before.

On one hand, there’s the intoxicating promise of a new affair. On the other hand, there’s the ring.

Producer Kyle Lehning’s work on this track, and on the entire landmark Storms of Life album it anchored, is a study in restraint. Where his contemporaries were adding layers, Lehning was peeling them away. The recording breathes. There is space between the notes, an intentional quiet that allows the gravity of the lyric and the richness of Travis’s voice to fill the room.

The song opens with a foundational acoustic guitar, a simple figure that feels like a man nervously tapping his fingers on a bar top. Then comes the steel guitar, played with heartbreaking precision by Paul Franklin. It isn’t just an accent; it’s the narrator’s conscience, sighing with regret and longing. It’s the sound of a heart being pulled in two directions.

Listening back now on a quality pair of studio headphones, the clarity of Lehning’s vision is staggering. You can hear the subtle woodiness of the bass, the gentle brushwork on the snare, and the sparse, foundational chords of the piano. Each instrument has its place, and no element crowds another. This wasn’t a wall of sound; it was a carefully arranged diorama of heartache.

At the center of it all is that voice. Randy Travis was still in his mid-twenties, but he sang with the gravitas of a man twice his age. His baritone isn’t forceful; it’s resonant. There’s a natural, unhurried cadence to his delivery, a slight North Carolina drawl that sands the edges off each word, making the confession feel intimate and true. He doesn’t oversell the drama; he lets the words do the work, inhabiting the character with a sincerity that was profoundly absent from the airwaves.

It’s a quiet war waged in three minutes, where the battlefield is a barstool and the only armor is a thin circle of gold.

This piece of music works because it captures a universal human moment. It’s the flicker of temptation, the mental calculation of risk and reward, the sudden, heavy awareness of consequence. The first verse lays out the flirtation, the mutual attraction, the open door to infidelity. The pull is real. You can almost feel the warmth of the bar, hear the low chatter and the clinking glasses.

But then the chorus hits, and the camera zooms in on that gold band. “But on the other hand,” Travis sings, his voice dropping with the weight of the realization, “there’s a golden band.” It’s a line that lands like a physical object. The song pivots entirely on that phrase, turning from a story of temptation into a story of loyalty. The ring isn’t just a piece of jewelry; it’s a character in the drama, a silent, powerful anchor.

Imagine a traveling salesman in a lonely motel room, the glow of the television painting the walls blue. He hears the song on a late-night radio station, and the simple story cuts right through his exhaustion. He glances at the indentation on his own ring finger, a silent testament to the life and the love waiting for him hundreds of miles away. The song doesn’t judge him; it understands him.

Or think of a young couple, swaying on a dance floor in a small-town VFW hall. The song comes on, and they pull each other a little closer. They’ve had their own storms, their own moments of doubt. But the song’s resolution—”I’m going home to be a family man”—reaffirms the choice they make every day. It’s a quiet celebration of the unglamorous, essential work of keeping a promise.

This is the power of great country songwriting. It takes a complex emotional situation and boils it down to a tangible, relatable image. The entire album, Storms of Life, is built on this foundation of authenticity. It was a commercial and critical titan, establishing Travis as a genuine superstar and setting the sonic template for the next decade of mainstream country.

The influence of “On The Other Hand” is immeasurable. It kicked open the doors for artists like Alan Jackson, Travis Tritt, and Clint Black. It made acoustic instruments and sincere, story-driven lyrics commercially viable again. It reminded Nashville that the genre’s strength wasn’t in its ability to mimic pop, but in its courage to stand apart. For anyone who appreciates true premium audio fidelity, this recording remains a benchmark for clean, emotionally direct production.

To listen to “On The Other Hand” today is to be transported. It’s a reminder of a time when a song could change the direction of an entire genre not with bombast, but with quiet conviction. It’s the sound of a man choosing not what he wants in the moment, but who he wants to be forever. It’s a perfect country song. Go back and listen again. Don’t just hear the melody; feel the weight of the choice being made in the silence between the chords.

Listening Recommendations

- George Strait – “The Chair”: Shares a similar era and a narrative cleverness built around a single, inanimate object telling the story.

- Keith Whitley – “Don’t Close Your Eyes”: Captures the same profound, baritone-led vulnerability and deep-seated heartache with masterful restraint.

- Vince Gill – “When I Call Your Name”: Features a powerful, emotionally pure vocal performance over a classic, steel-drenched country arrangement.

- Alan Jackson – “Here in the Real World”: A direct descendant of the neotraditional sound Travis pioneered, full of earnest authenticity and plain-spoken truth.

- The Judds – “Grandpa (Tell Me ‘Bout the Good Old Days)”: Evokes a similar sense of nostalgia and longing for a simpler, more honest time in music and life.

- Don Williams – “I Believe in You”: Showcases the immense power of a gentle, sincere vocal delivery and beautifully understated production.