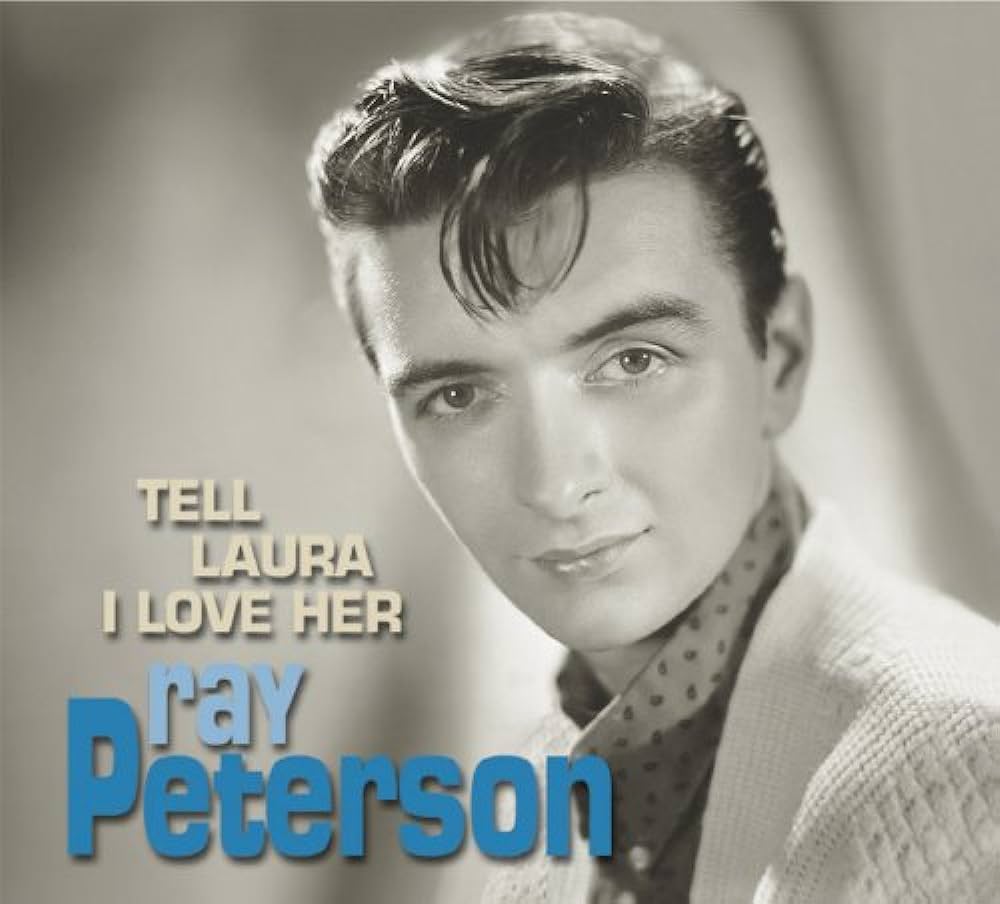

The year is 1960. The air is thick with the promise and peril of youth, a time when a quick drive and an impulsive decision could still feel like the stuff of epic romance. This was the moment Ray Peterson stepped into a New York studio booth for RCA Victor, his extraordinary four-octave voice poised to deliver a narrative so overwrought, so deliciously morbid, that it would instantly carve a permanent groove into the history of pop music. The song was “Tell Laura I Love Her,” and it was—and remains—an absolute marvel of cinematic, breathless tragedy.

This wasn’t a track plucked from a sprawling album of diverse material; it was a pure, self-contained phenomenon. Released as a stand-alone single, it was the sound of a very specific cultural moment: the rise of the “death disc,” a trend that traded the sugar-sweet cooing of earlier teen idols for something more genuinely, theatrically emotional. Peterson, a Texas native known for his robust, clean vocal delivery, had already scored a hit with the dramatic ballad “The Wonder of You,” but this piece of music, written by the formidable duo Jeff Barry and Ben Raleigh, would cement his legacy. The producers credited on the track, Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore—often referred to simply as Hugo & Luigi—understood the assignment perfectly, crafting an arrangement that was simultaneously lush and utterly stark, creating the necessary space for Peterson’s powerful voice to command the tragic stage.

The song’s architecture is everything. From the opening moments, “Tell Laura I Love Her” commits to its melodrama with a striking lack of self-consciousness. The central narrative is, after all, preposterous: a poor boy named Tommy enters a stock-car race to win a thousand-dollar prize, intending to buy his beloved Laura a wedding ring, only to meet a fiery, fatal crash. The stakes are impossibly high, the emotional payoff brutally efficient.

The production is the vehicle for this narrative high-stakes drive. The arrangement immediately sets a tone of crushing inevitability. The backing features a prominent piano chord progression, simple and direct, which anchors the entire sound. It’s played with a heavy, slightly distant quality, lending a funereal quality even before the lyrics turn truly dark. Over this, a clean, reverberant guitar line threads a mournful counter-melody, a delicate contrast to the rhythmic plod of the bass and drums.

Peterson’s vocal performance is what elevates this from simple schlock to enduring classic. He doesn’t sing the story so much as he narrates a Greek tragedy in miniature. His range, which was truly exceptional, allows him to rise in volume and intensity, yet he manages a restraint in the initial verses that makes the eventual catharsis so much more impactful. The dynamic shift is expertly managed; his voice is close-miked and intimate when Tommy is just planning his dash for cash.

The emotional crescendo arrives, of course, with the famous bridge: “The crowd roared as they started the race…” Here, the instrumentation swells dramatically. The addition of a string section—unconfirmed, but certainly prominent brass or orchestral backing—pushes the song’s energy forward, mirroring the rising speed of the stock car. The brass stabs are sharp, almost violent, before the sound dissolves into a horrifying, pregnant pause for the crash.

“There is no finer example in early rock-era pop of the calculated deployment of quiet melodrama for maximum emotional collateral.”

Then comes the gut punch: the final, dying words delivered in a whisper, then repeated, building back up to a full, pleading cry. Peterson utilizes his full register for the final, drawn-out syllables of “never die.” This section, with its extreme dynamic shifts and theatrical voicing, demanded premium audio quality for listeners to fully appreciate the contrast between the strained, dying whisper and the full, heartbroken declaration. It’s a moment designed to evoke tears, gasps, and countless re-plays on cheap transistor radios.

The sheer audacity of the subject matter—a literal death pronouncement—sparked predictable controversy. In the United Kingdom, for instance, Peterson’s version was reportedly suppressed by Decca Records for being “too tasteless and vulgar,” leading to a rival cover version that rocketed to number one. This very controversy only amplified the song’s mythic status in the United States, where it peaked respectably within the Top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100 chart. The song didn’t just reflect the era’s fascination with teenage love and loss; it aggressively molded it, setting the bar for dramatic balladry for years to come. Tommy’s doomed quest, driven by the desire to give his girl “everything” and a wedding ring, is a hyperbolic expression of the economic anxiety and material dreams of the young postwar generation. It’s the sound of a desperate idealism, literally crashing and burning.

The enduring appeal of “Tell Laura I Love Her” lies in its effective, if heavy-handed, fusion of rock and roll sensibility with Tin Pan Alley polish. It possesses the raw, urgent energy of rock’s burgeoning narrative focus, yet it is arranged with the sweep and emotional breadth of a grand pop standard. The chords are deceptively simple, often the first that aspiring musicians seek out guitar lessons for, yet the layered, dramatic soundscape is anything but basic. Every generation seems to discover this miniature opera, whether through old vinyl spins or a sudden encounter on a music streaming subscription playlist, realizing that the teenage angst of 1960 is simply human angst, dressed up in a racing uniform.

Listening Recommendations

- Mark Dinning – “Teen Angel” (1959): The immediate predecessor and thematic sibling, setting the benchmark for the death disc genre with a similar structure.

- J. Frank Wilson and the Cavaliers – “Last Kiss” (1964): Another car crash tragedy ballad, adopting a slightly more rock-leaning, grief-stricken tone.

- The Shangri-Las – “Leader of the Pack” (1964): The definitive girl-group take on the death disc, using dramatic sound effects and spoken word narrative.

- Conway Twitty – “Lonely Blue Boy” (1960): Shares the period’s penchant for deep, emotional vocalizing and dramatic pauses, minus the fatal accident.

- Roy Orbison – “Only the Lonely” (1960): Captures the same soaring, melodramatic vocal style and orchestral sweep that defined the era’s grand ballads.

“Tell Laura I Love Her” might be easy to dismiss as high-camp novelty, but beneath the tear-stained handkerchief, it’s a masterclass in emotional delivery and production for its time. Ray Peterson’s legacy rests upon this perfectly executed, tragically resonant four minutes. Don’t listen to it; feel it—and remember the promise Tommy died trying to keep.