The late spring of 1963 felt like an ending, though few recognized it at the time. The great American rock and roll machine, built on the swagger of Elvis and the clean-cut charm of Ricky Nelson, was about to meet the hurricane force of the British Invasion. But before that cultural earthquake struck, there was a moment of elegant, sophisticated pop that captured the quiet heartbreak of the era: Rick Nelson’s single, “String Along.”

I often listen to this piece of music late at night, the sound drifting from vintage speakers in a dim room. It doesn’t roar. It doesn’t swagger. It glides, a subtle, sorrowful current that perfectly soundtracks an overcast memory. The song itself, a Jimmy Duncan and Bobby Doyle composition, is a simple, potent statement on feeling expendable in a relationship.

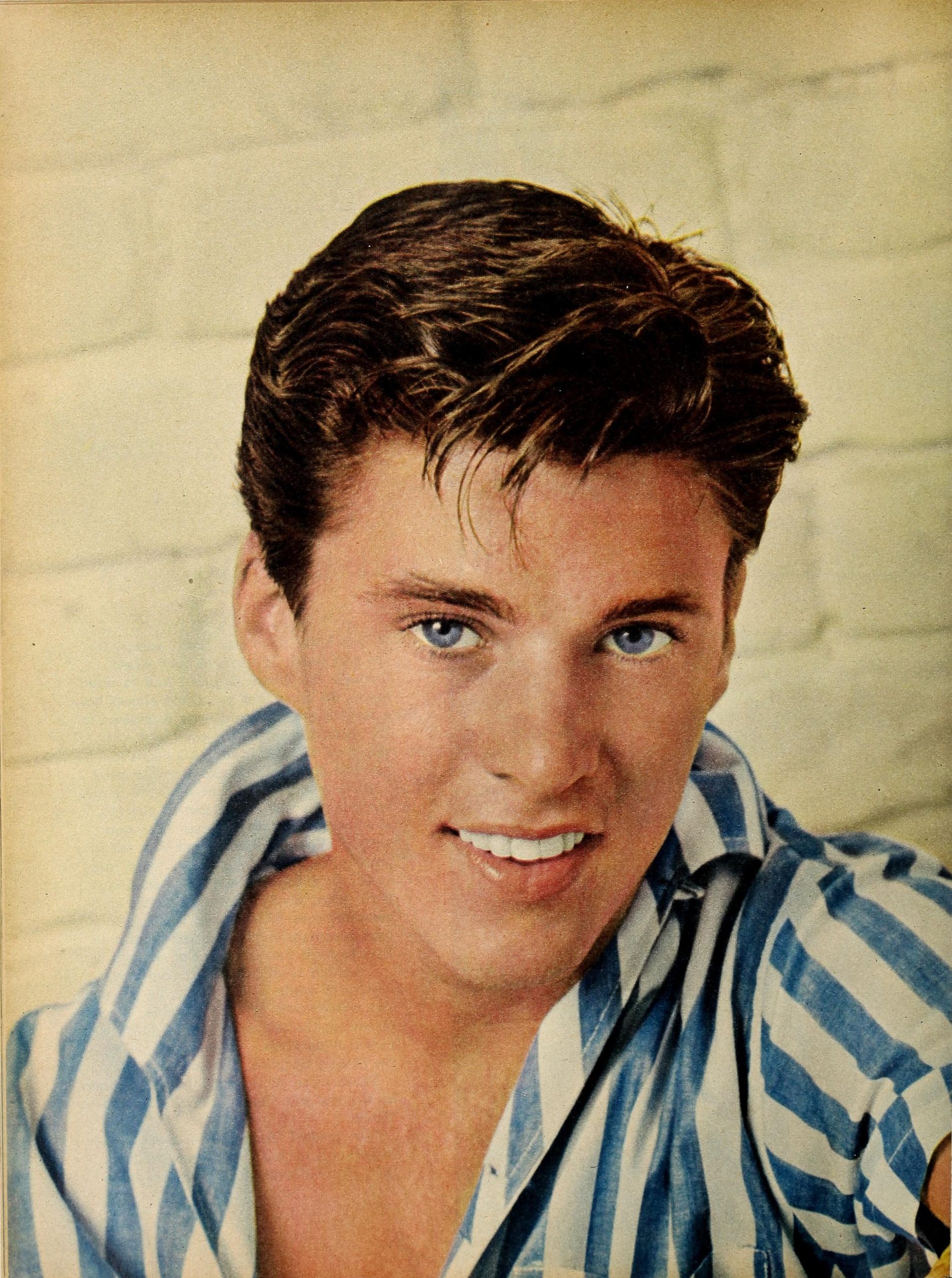

Nelson, now officially known as Rick, having shed the “y” from his teenage moniker on his 21st birthday, was navigating a crucial shift in his career. For years, he was the television darling of America, performing his hits weekly on The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. His previous label, Imperial, had provided a foundation for his signature rockabilly sound, powered by the incomparable guitar work of James Burton.

But 1963 marked a massive transition: Nelson left Imperial for a lucrative, multi-year deal with Decca Records. This move was intended to signal artistic and commercial maturity. “String Along,” released in May 1963, was an early fruit of this new contract, appearing later that year on his debut Decca album, For Your Sweet Love.

The production chair for this new chapter belonged to Charles “Bud” Dant. Dant’s approach for For Your Sweet Love and its singles, including this one, was a departure from the raw energy of the Imperial years. He wrapped Nelson’s cool, gentle vocal delivery in a lush velvet bow. The result is a sound that owes less to Sun Records and more to the slick, orchestrally enhanced pop dominating the early 1960s charts.

The immediate impression of the song’s arrangement is one of texture and control. The famous, slightly tremulous lead guitar that had been James Burton’s signature is toned down, serving the melody rather than dominating it. Instead, we hear a tightly marshalled rhythm section—subtle drums and a warm, guiding bass line—laying the foundation for the melodic instruments.

The arrangement hinges on a magnificent, cascading string section. These violins and cellos do not just sit in the background; they articulate the song’s melancholic mood. They rise and fall dramatically during the instrumental breaks, giving the song an undeniable cinematic sweep. This is sophisticated studio craft designed for an audience ready to move beyond the raw edge of the 1950s.

A quiet, yet essential element is the work on the piano. It provides a clean, bright counterpoint to the weeping strings. Its chords are voiced high, adding a sparkling clarity that stops the piece from descending entirely into melodrama. It’s a classic example of how a few well-placed notes can lift a dense arrangement, offering rhythmic pulse alongside harmonic support.

“The String Along” narrative is compelling because it’s so universally resonant. The lyrics paint a picture of quiet desperation: “String along, that’s all I am, just your string along / Someone that you just seem to bring along whenever you are all alone.” It’s the voice of the person who knows their value is contingent, an emotional standby. This vulnerability was perfectly suited to Nelson’s voice. His signature cool, almost detached tenor—often criticized as being wooden—instead translates here as heartbreaking restraint. He is too cool, too proud to cry, but his delivery speaks volumes.

The record performed solidly, though perhaps not with the chart dominance of his peak years, hitting the upper registers of the charts, reaching the top 20 on the Cash Box chart and just a little lower on the Billboard Hot 100. This relatively modest performance in 1963 is often cited as evidence of Nelson’s slowing momentum. But a deeper look reveals a more complex truth.

The music landscape was fragmenting rapidly. The rockabilly fans were growing up, and the new crop of teens were about to be captivated by a far more aggressive sound from overseas. Nelson was trying to chart a course for longevity, a transition from “teen idol” to serious artist, an effort perfectly encapsulated by the shift in sound toward the elegant, orchestrated pop of his new label.

“String Along” wasn’t designed for a frantic teen dance floor; it was music for a thoughtful late-night drive. It’s the kind of song that sounds magnificent when played through quality home audio equipment, revealing the subtle interplay between the acoustic and electric elements.

Imagine a young man in 1963, parked by the ocean, the radio dial glowing. He’s listening to Rick Nelson sing about being a backup plan, and the melancholy wash of the strings feels intensely personal. He’s the string-along for a girl who’s waiting for the star quarterback to call. This quiet scene of romantic anxiety—the universal agony of knowing you’re second choice—is the true subject of the song.

The song resonates today because it stands at a crossroad. It contains the melodic structure of classic rock and roll, but is imbued with the sophisticated arrangements that would define the era of Burt Bacharach and later, the lush country-pop he would pioneer. It’s a moment of glamour, restraint, and an aching sincerity that many pop critics often overlooked due to Nelson’s TV origins.

“The greatest artists often find their most profound moments not in triumph, but in the exquisite articulation of surrender.”

A young Rick Nelson, whose face was literally framed by a television set for millions every week, used this new Decca contract to push beyond his own established image. He wasn’t just recycling his rockabilly hits for a new decade; he was embracing the role of a mature, sensitive interpreter of complex pop arrangements. This sophistication, this willingness to sound vulnerable and controlled all at once, is what makes “String Along” not just a relic of 1963, but an enduring document of American pop music.

It is a record that rewards close listening. The subtle dynamic shifts, the way Nelson leans into a word like “alone,” the beautiful, precise decay of the reverb on the vocal track—these details confirm the careful, high-fidelity production approach of producer Charles “Bud” Dant. It is a subtle triumph of melancholy pop craft.

Listening Recommendations

- “Fools Rush In” – Rick Nelson (1963): Another excellent, lush Decca single from the same era and producer, showing his mature vocal control.

- “Cathy’s Clown” – The Everly Brothers (1960): Shares the minor-key melodic sophistication and themes of romantic exploitation.

- “Only the Lonely” – Roy Orbison (1960): For the perfect blend of controlled pop vocal and dramatic, almost operatic string arrangements.

- “He’ll Have to Go” – Jim Reeves (1959): Captures the smooth, warm, country-tinged vocal pop timbre that Nelson was leaning into at Decca.

- “Wichita Lineman” – Glen Campbell (1968): A later example of a star blending folk, country, and orchestrated pop with supreme vocal cool.

- “Travelin’ Man” – Ricky Nelson (1961): Provides an essential counterpoint, showcasing the James Burton-led, high-energy Imperial sound he was leaving behind.