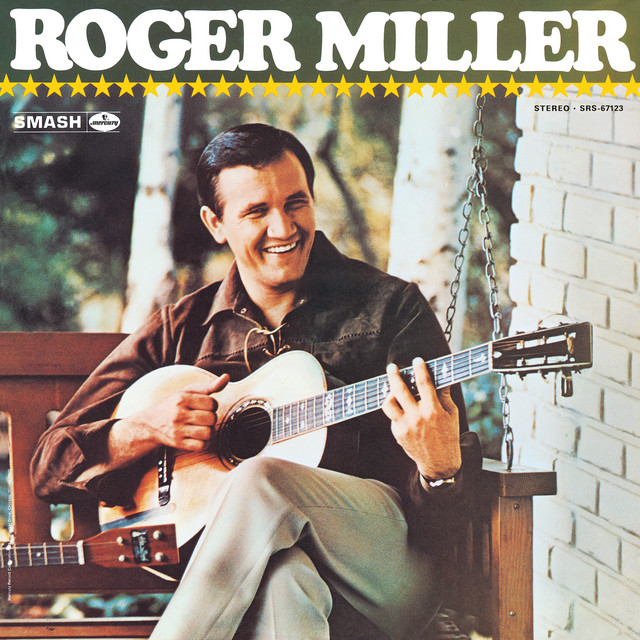

Roger Miller didn’t need to shout to be heard. He preferred the conspirator’s grin, the shrugging melody that sneaks up on you, the one-liner that doubles as a thesis. “England Swings” captures that sensibility in three quick minutes, one of those singles that float like a paper airplane into the room and then somehow lodge in the furniture of your memory.

I often imagine it spinning through a car radio on a fall afternoon, the air bright and a little cool, traffic slow enough to let you hum along. The year is the latter half of 1965, when the American charts were glinting with British accents and boulevards of imported guitars. It’s Roger Miller, though, a Nashville polymath on Smash Records, who holds up a mirror to that whole phenomenon and angles it just so. He writes the postcard from “Swinging London,” stamps it with a wink, and drops it in the mailbox of country-pop.

By this point, Miller had already flung off a string of hits—“Dang Me” had introduced his deadpan wit in 1964, and “King of the Road” had shown how a pastoral, hobo-philosopher melody can suddenly feel like a proverb. “England Swings” arrives as part of that golden run, included on his 1965 album The 3rd Time Around, with Jerry Kennedy, the in-house steadier at Smash, again shepherding the sessions. You hear continuity: the small-band snap, the studio polish that doesn’t dazzle so much as gleam, the sense that every instrument is doing just enough and no more.

The arrangement is light, almost weightless, and that’s the trick. Drums tip-tap a breezy shuffle. The bass walks with a neighborly stride, never tugging attention away from the vocal. A spry guitar flicks little rhythmic sparks between the lines, while a compact piano figure dots the phrases like a familiar streetlamp. There’s room for air—Miller songs often feel mic’d as if the band were playing in a tidy living room, not a cavernous hall. You catch the attack of the pick against the string, the quick decay on the snare, the soft room reverb that turns edges into curves.

“England Swings” is thick with images, yet the tone remains offhand. The vocal glides between sung and spoken, each syllable placed with the comic timing of someone who knows where the laugh lives—and, more importantly, where it doesn’t. He never oversells the joke. He lets it breeze by like the red bus in the corner of your eye. What could have been a novelty becomes something friendlier and more elastic: a travelogue, a listener’s smile, a gentle rib.

Listen to the first verse and you’ll hear Miller’s phrasing do the heavy lifting. He leans on certain vowels as if testing the balance of the line, teasing out a musical lilt that mimics the sway of a boat on the Thames. The consonants land light; nothing clunks. He sings “Swinging London” without the exclamation point—an editorial decision that dates the song less than you’d expect. His voice sits forward in the mix, and you can tell the microphone is set to flatter a conversational volume, not a belter’s blast. At times, there’s the faintest sheen that suggests a ribbon mic’s soft-edged fidelity, a tactile gloss that matches the song’s tourist-brochure charm.

There are details both sonic and cultural tucked into the bones of the track. Mid-’60s Nashville had quietly absorbed pop gestures from both coasts and from across the Atlantic. Miller’s band nods to that, but keeps the frame country: shuffle rather than beat-group stomp, clean lines instead of fuzz. Even so, the rhythmic sway has a transatlantic wink. It’s not Merseybeat, but it can see Liverpool from the window.

“England Swings” belongs to a lineage of Roger Miller recordings that value brevity as a moral good. There’s not a single wasted bar. A little whistle motif, when it appears, is tossed off like a friend’s aside, a flash of daylight that recurs without becoming precious. In a different production, that motif might have been doubled by strings or padded with woodwinds. Here, it is a pocket flourish—a sketch, not a mural. Because of that restraint, the track breathes. It’s a piece of music that understands how charm travels quickest when it packs light.

If you sit with headphones and really hone in, the dynamics read like good conversation. The band steps forward to underline a punchline, then leans back to let the chuckle land. The guitar is percussive more than lyrical here, a right-hand engine whose strums lock with the snare. The piano is a rhythmic neighbor, chiming in on downbeats as if nodding along. Imagine brushing some grain off a table—that’s how the brushed snare feels, a soft abrasion that keeps time and polishes the surface at once.

Miller’s writing also shows his equilibrium between specificity and silhouette. He alludes to icons—the way postcards flatten a city into three or four symbols—and avoids anchoring the track to a single news headline. As a result, the satire ages gently. It isn’t a roast; it’s a fond caricature. A listener who never watched a single British variety show in 1965 can still follow along.

Historically, it’s worth noting how the song nested in Miller’s career arc. After a run of breakout singles on Smash, he was both hitmaker and brand—his name signified a style: light but not slight, wry but not cruel. “England Swings” tightened that brand. It crossed from country to pop radio in the United States, and contemporary accounts place it among the bigger songs of the season, hovering in the top tier of the Hot 100 while remaining a presence on country playlists. It’s proof of Miller’s unique bridgework in the era of the British Invasion: an American voice that could admire, jest, and synthesize.

One reason the track feels so modern is the mix’s sense of intimacy. You can almost see the semi-circle of players, you can almost measure the room in a few claps. No giant echo chamber. No cavern of reverb to inflate the image. Just a tidy studio where human scale is the point. It’s the same quality that lets the lyric smuggle warmth into irony. When he sings about places he’s not from, he sounds like a guest who brought pie, not a stranger with a megaphone.

“England Swings” also intersects with the way we hear lightness today. In an era of maximal pop and maximal country-pop—choruses stacked thirty tracks high—Miller’s economy scans as almost artisanal. It’s bright but never brittle, witty but never weaponized. If you’ve ever tried to record something “simple,” you know how hard that is. Simplicity can go thin; this doesn’t. The bass and drums create a firm handrail, the vocal slides alongside, and the embellishments (that whistle, those ornamental fills) appear like well-timed glances.

Consider three small listening vignettes that illuminate the song’s reach now. First, a late-night kitchen: the day’s clutter set aside, a little speaker on the counter. You cue the track and hear the shuffle counter your own restless energy. The lyric comes across as a kind of posture adjustment—see the world, grin at its pageantry, don’t take the parade too seriously. Second, a commute among billboards selling tomorrow. The song becomes a counter-ad—a reminder that wonder can be handmade and unhurried. Third, a living-room Saturday with the windows cracked and the dust motes lazy in the tilted sun. The whistle turns into a domestic wind chime. You can’t force that effect; you have to write and record for it.

“England Swings,” for all its postcards, is really about movement. The arrangement walks rather than sprints. The humor floats rather than jabs. Even the rhyme choices feel like strolling past storefronts, glancing left, glancing right. This motion opens a door for listeners who think they “don’t like country.” They might not hear twang; they might hear travel.

“‘England Swings’ proves how a featherweight touch can carry a heavyweight idea: joy as a way of seeing, not just a mood.”

It’s tempting to label the track a novelty and move on. But novelty songs rarely linger without a gimmick to keep them propped up. “England Swings” lingers because the craft hides in plain sight. The groove is narrow but sturdy; the melodic cells are compact but catchy; the vocal inhabits an easy register where Miller sounds like himself. If you’ve ever pored over sheet music, you know the notation for a song like this will look deceptively bare—whole measures of uncomplicated rhythm, minimal accidentals—until you try to perform it and realize the feel is the secret ingredient.

Thematically, the song sits in conversation with “King of the Road.” Both pieces marvel at freedom—one through the American vagabond’s inventory, the other through a tourist’s montage. Both take archetypes and turn them into friendly cartoons. And both resist the condescension that often haunts “clever” pop. Miller’s satire includes himself in the frame. He’s the smiling narrator who knows he’s also a spectator.

From a timbral perspective, a modern listener might notice how midrange-forward the recording is. Bass is present but not club-thick. Highs are crisp but not glassy. Vocals ride the front bench; guitars and keys sit across the aisle. On better studio headphones, you can pick out the ghostly tail of room reverb at the end of certain phrases, the slight swell of breath before a consonant snaps shut. Those tiny sounds are the record’s fingerprint.

Because of its subject, “England Swings” inevitably interacts with the British Invasion mythos. But it also speaks to something broader—the way pop culture gets packaged and mailed back to itself. Miller’s song is a souvenir shop where nothing costs more than a grin. He’s not capturing London; he’s capturing the American fantasy of London. That difference keeps the piece elastic. We all carry postcards of places we haven’t been.

Some will come to the track through compilations, others through The 3rd Time Around, others via radio oldies blocks that splice decades into hour-long highways. However you arrive, the context strengthens the listen. On the album, “England Swings” plays like a bright window in a row of character studies; as a single, it’s an ambassador from a small republic called Roger Miller, population one. The label at the time, Smash, understood the cross-format potential and positioned Miller as a storyteller who could hop fences without changing boots. That strategy worked, and this song is one of the best arguments for it.

More than half a century on, what remains is not just a clever conceit but a specific sound: the brush of the snare like a street sweeper at dawn, the soft clink of the piano, the guitar quilting the rhythm with warm stitches, a voice that never hurries the laugh. You feel welcomed. You feel, oddly, seen.

The glamour vs grit contrast gives the track its aftertaste. On one hand, the imagery is glossy—double-decker buses, monocles in cartoons, the gleam of shop windows. On the other, the performance is pragmatic—small band, quick setup, nothing gilded. That balance is why the song doesn’t wilt when fashions change. Glamour dates; good timing doesn’t.

If you’re exploring Roger Miller now, this is an ideal starting gate. It shows the range of his humor without the heavier satire; it shows his melodic knack without the big moral. It’s a gateway for people who love folk-pop and think country is a different planet. And it has that crucial Miller quality: it ends and you feel better, not because it promised anything, but because it reminded you that delight can be distilled.

The final note fades like a door closing on a sunny corridor. You might play it again, and again it will feel short, like a friend who never overstays. Not every song needs to be an essay. Some can be a postcard that keeps arriving on time.

Listening Recommendations

-

Roger Miller – “King of the Road” — Kindred wit and an easy-rolling groove, turning minimalist arrangement into philosophy.

-

Roger Miller – “Dang Me” — The lean, witty template in its purest form, with a shuffle that clips along like a clever grin.

-

The Kinks – “Dedicated Follower of Fashion” — A British satire of Swinging London from the inside, all bright vowels and sharp edges.

-

Herman’s Hermits – “Mrs. Brown, You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter” — Soft-focus British Invasion pop that pairs well with Miller’s lightness.

-

The Kinks – “Sunny Afternoon” — Languid, wry social portraiture with melodic sunbeams and a similar conversational vocal.

-

Chad & Jeremy – “A Summer Song” — Gentle ’60s breeze, close-mic intimacy, and a pastel mood that complements Miller’s postcard.

Takeaway: “England Swings” remains a small marvel of proportion—wry, brisk, and human-scaled—proof that a song can travel the world with nothing more than a good line, a modest band, and the confidence to smile.