There are live albums, and then there are moments in history that happen to be recorded. Roy Orbison and Friends: A Black and White Night belongs firmly to the second category. Released in 1989, the album captures a 1987 television special filmed in stark monochrome, presenting Roy Orbison at the center of a reverent gathering of peers and admirers. Issued not long after Orbison’s sudden passing in December 1988, the record became an unlikely chart success—reaching No. 12 on the Billboard 200 and topping the UK Albums Chart—proof that its resonance extended far beyond nostalgia. What unfolds across these performances is less a comeback than a benediction: a quiet coronation of an artist whose influence had shaped generations.

The timing of the project gives it an almost mythic weight. By the mid-to-late 1980s, Orbison’s voice—once ubiquitous on radio in the early 1960s—had receded from the mainstream spotlight, even as his songwriting DNA lived on in countless hits by others. The black-and-white concept did not attempt to “modernize” him. Instead, it framed him as timeless. The visual austerity removes era-specific distractions, leaving only silhouette, sound, and the emotional architecture of the songs. In a decade defined by neon gloss and digital sheen, this choice felt radical. It asked the audience to listen harder.

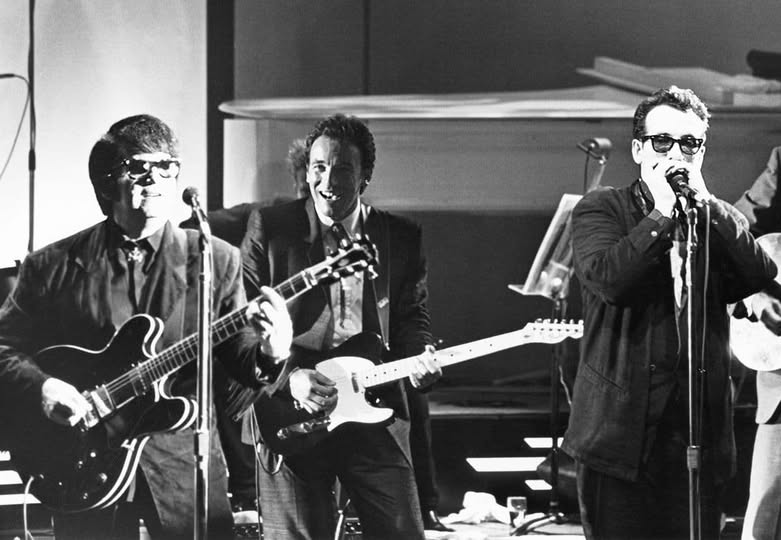

The “friends” assembled onstage are not cameos designed to steal focus. They are witnesses to a lineage. Bruce Springsteen, Elvis Costello, Tom Waits, k.d. lang, and Bonnie Raitt share harmonies and glances that feel less like performance and more like acknowledgment. None of them try to “update” Orbison’s catalog. They step back, blend in, and let the songs breathe. The message is subtle but unmistakable: this is the wellspring. What we now call roots-rock, heartland rock, alternative country, and torchy Americana all drink from this source.

Musically, the set reveals how meticulously Orbison built his world. Classics like “Oh, Pretty Woman,” “Only the Lonely,” and “Crying” unfold with architectural precision. Orbison’s voice does not overpower; it ascends through control. He was never a shouter. His genius lived in tension—melodies that climb toward catharsis, then hover, suspended between ache and acceptance. In this stripped-down setting, those qualities feel magnified. Without color, without spectacle, the emotional contrasts sharpen. Joy gleams. Sorrow cuts clean. The arrangements respect space, allowing Orbison’s phrasing to linger in the air. You can hear the room breathe.

The band, too, understands restraint. Guitars shimmer rather than roar; rhythms support rather than dominate. The sonic palette honors Orbison’s operatic instincts without turning the performance into a museum piece. This is living music, animated by musicians who clearly recognize the privilege of standing inside another artist’s cathedral. There’s a humility to the playing that feels increasingly rare in star-studded collaborations. Nobody grandstands. Everybody listens.

Culturally, the album now stands as something rarer than a great live record. It is a farewell that did not know it was one. Orbison performs with calm authority, unaware that these images would become among the final definitive frames of his career. That unintentional finality gives the project its lasting power. It isn’t haunted by decline or regret. There is no sense of an artist chasing relevance. Instead, we see Orbison in full command of his gifts, surrounded by people who understand their debt to him. The result is a portrait of artistic continuity—of how songs travel through time, changing voices without losing their core.

The black-and-white aesthetic also does something quietly radical: it collapses eras. Orbison’s earliest hits belong to the early rock-and-roll and pop ballad tradition, yet here they sit comfortably alongside artists who emerged decades later. The visual language makes it all feel of one moment, one lineage. In an industry obsessed with cycles of hype and reinvention, this performance argues for permanence. Great songs do not expire. They wait.

There is, too, a sense of community in the way the night unfolds. Between verses and harmonies, you catch smiles, nods, the small human gestures of musicians sharing a room rather than a spotlight. It reminds us that legacy isn’t built only on charts and accolades, but on the quiet respect of peers. That respect becomes audible here. You hear it in the way Springsteen leans into a harmony, in the way Costello watches Orbison’s phrasing before stepping in, in the way the ensemble shapes dynamics around the lead voice rather than competing with it.

Decades on, Roy Orbison and Friends: A Black and White Night feels less like an artifact and more like a still photograph in sound—a moment where time pauses long enough for greatness to speak for itself. It doesn’t plead for remembrance. It simply remains. If you’re discovering it for the first time, you’re not “catching up” to history; you’re stepping into a room where history is still happening.