Table of Contents

ToggleThere are songs that whisper their way into history—and then there are songs that burst through the speakers like a runaway train. Roy Orbison’s 1963 rendition of “Mean Woman Blues” belongs firmly in the latter category. It is wild, urgent, unapologetic rock and roll—three minutes of breathless obsession wrapped in a pounding rhythm and delivered by one of the most distinctive voices in popular music.

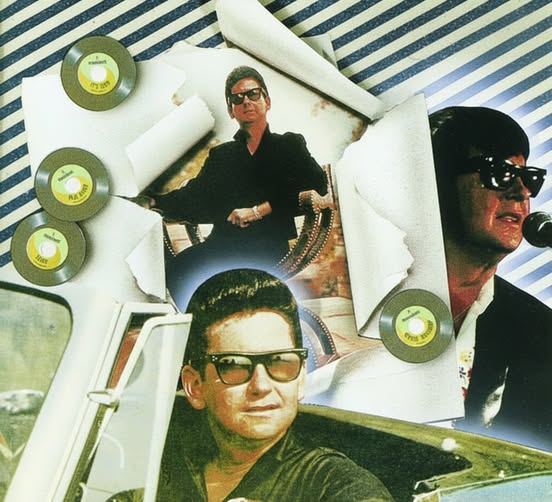

When people think of Roy Orbison, they often recall the sweeping drama of “Crying,” the aching romance of “Only the Lonely,” or the cinematic melancholy of “Blue Bayou.” Yet to limit Orbison to his operatic ballads would be to overlook one of the most electrifying sides of his artistry. “Mean Woman Blues” is proof that behind the dark sunglasses and emotional crescendos stood a performer who could unleash raw, primal energy with unmatched conviction.

More than sixty years later, this track still crackles with life.

A Chart-Smashing Double Threat

Released on August 1, 1963, on the Monument label, “Mean Woman Blues” arrived as the A-side of a single paired with what would become another Orbison classic, “Blue Bayou.” The combination was nothing short of strategic brilliance. On one side, listeners got a driving, sweat-soaked rocker. On the other, a tender, heart-wrenching ballad. Together, they showcased the astonishing range of “The Big O.”

In the United States, “Mean Woman Blues” stormed the charts, climbing to Number 5 on the Billboard Hot 100. Its B-side companion, “Blue Bayou,” also made an impact, peaking at Number 29. Across the Atlantic, British audiences embraced the single as a double A-side, propelling it to a joint peak of Number 3 in the UK.

This wasn’t just commercial success—it was cultural validation. By 1963, Orbison had already established himself as a global force, but this release reinforced his status as one of rock’s most versatile and compelling figures. He could make audiences swoon with heartbreak one moment and have them stomping their feet the next.

From Elvis to Orbison: Reinventing a Rocker

Interestingly, “Mean Woman Blues” was not originally written for Roy Orbison. The song was penned by songwriter Claude Demetrius and first recorded by Elvis Presley for the soundtrack of his 1957 film Loving You. Presley’s version was confident and swaggering—classic early Elvis with a smirk and a hip shake.

But when Orbison stepped into the studio in April 1963 to record his interpretation, he transformed the song entirely.

Where Presley strutted, Orbison burned.

His version is faster, sharper, and far more intense. It doesn’t merely tell the story of a man captivated by a troublesome woman—it sounds like the man is unraveling in real time. The tempo pushes forward relentlessly, the rhythm section drives hard, and Orbison’s voice cuts through the arrangement with a rawness that feels almost dangerous.

It’s not cool detachment. It’s fever.

The Story: Captivated by Chaos

At its core, “Mean Woman Blues” tells a simple, archetypal blues story. A man falls for a woman who is undeniably trouble. She’s “mean as she can be.” He knows it. Everyone knows it. But logic has no power here.

The lyrics paint her as irresistible: ruby lips, shapely hips, a magnetic presence that makes “old Roy-oy flip.” She’s not just attractive—she’s overwhelming. She dominates his thoughts, disrupts his peace, and ignites his senses.

What makes Orbison’s performance so compelling is how fully he inhabits that emotional conflict. This isn’t a polished Casanova boasting about a wild romance. This is a man possessed—caught in the push and pull between desire and destruction.

He shouts, wails, and practically explodes through the twelve-bar blues structure. His delivery feels urgent, almost manic. Each repetition of the chorus intensifies the sense that he is spiraling deeper into something he can’t control.

The brilliance lies in that tension: he recognizes her cruelty, yet he can’t walk away.

Logic vs. Passion: A Timeless Struggle

Beneath its driving beat and rockabilly flair, “Mean Woman Blues” captures one of the most universal human experiences—the battle between reason and emotion.

We’ve all been there.

That relationship that makes no sense. The attraction that defies warning signs. The connection that feels electric but destructive. You know it’s not good for you. Friends tell you so. Your instincts whisper caution. Yet you stay, pulled in by chemistry, by excitement, by something that feels bigger than consequence.

Orbison doesn’t intellectualize this conflict. He embodies it. The frantic instrumentation mirrors the chaos inside the narrator’s heart. The pounding rhythm section—performed by Nashville’s legendary A-Team session musicians—creates a sense of forward momentum, as if the story can’t slow down long enough for reflection.

It’s rock and roll in its purest form: simple structure, honest emotion, unfiltered energy.

And that’s why it still resonates.

A Different Shade of Orbison

One of the most fascinating aspects of “Mean Woman Blues” is how it challenges the common perception of Roy Orbison. Popular culture often frames him as the melancholic balladeer—the man who sang of loneliness and longing in soaring, operatic tones.

But Orbison was never one-dimensional.

Before the dramatic crescendos and orchestral arrangements, he was deeply rooted in rockabilly and rhythm and blues. “Mean Woman Blues” reconnects him to that foundation. It strips away the lush strings and spotlight theatrics and reveals a performer who could command a stage with sheer vocal force.

Listen closely, and you’ll hear the grit beneath the polish. The control beneath the frenzy. Even at his most unhinged, Orbison’s phrasing remains precise, his timing impeccable.

It’s chaos, but it’s crafted chaos.

The 1987 Revival: A Black & White Night

If anyone doubted the song’s enduring power, Roy Orbison silenced them in 1987 with his legendary television special, Roy Orbison and Friends: A Black & White Night.

Backed by an all-star lineup that included Bruce Springsteen, Elvis Costello, Tom Waits, and other rock luminaries, Orbison delivered a blistering performance of “Mean Woman Blues.” Dressed in black, standing center stage, he unleashed the same fiery energy he had captured decades earlier.

The crowd roared. Fellow musicians grinned in admiration. The moment felt timeless.

It was more than nostalgia—it was proof that the song’s vitality had not faded. Even in an era dominated by synthesizers and polished pop production, the raw electricity of classic rock and roll still hit like a lightning bolt.

Production and Sound: Pure Rock and Roll Muscle

Part of what makes Orbison’s version so explosive is the production. Monument Records understood how to capture immediacy. The guitars are crisp and biting, the drums punch forward, and the bass line anchors the chaos with steady authority.

There’s no excess. No overproduction. No distraction.

Just rhythm, attitude, and voice.

The arrangement leaves space for Orbison’s vocals to dominate, and dominate they do. His dynamic control—moving from sharp declarations to near-yelps of desperation—adds texture to what could have been a straightforward rocker.

Instead, it becomes a psychological portrait set to a backbeat.

Why It Still Matters

In a world of algorithm-driven playlists and meticulously engineered pop singles, “Mean Woman Blues” feels refreshingly direct. It reminds us of a time when a three-minute track could capture the entirety of a human struggle—no filters, no irony.

It’s sweaty. It’s urgent. It’s emotionally honest.

And perhaps that’s why it endures.

Roy Orbison didn’t just sing about heartbreak and desire. He felt them out loud. “Mean Woman Blues” stands as a testament to his versatility and to the primal roots of rock and roll itself.

For longtime fans, it’s a thrilling reminder that Orbison could rock as fiercely as he could weep. For new listeners, it’s an invitation to rediscover an era when music moved not just your ears—but your pulse.

Turn up the volume. Let the rhythm take over. And experience once again the roaring cry of a man ensnared by love he knows he can’t escape.

Some songs fade with time.

“Mean Woman Blues” still burns.