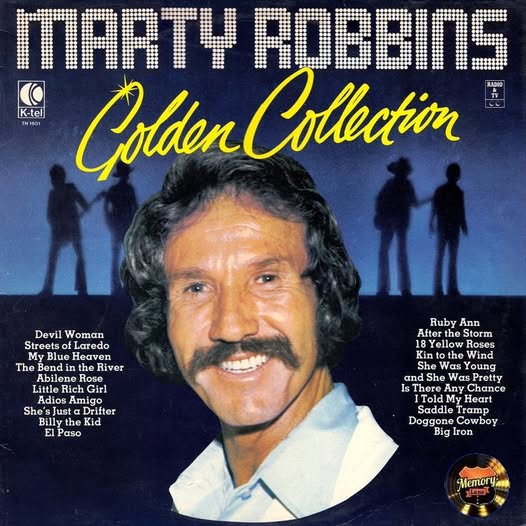

When we speak of timeless Western ballads, few voices echo across the prairie of memory quite like Marty Robbins. His 1959 masterpiece album, Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, remains one of the most defining concept records in country music history—an album that didn’t merely tell stories but built an entire mythos of the American frontier.

While hits like “El Paso” captured mainstream attention, it is often the deeper cuts that reveal the true emotional depth of Robbins’ artistry. “Saddle Tramp” stands as one of those hidden treasures—an evocative Western tale that may not have climbed the singles charts, yet plays a crucial role in shaping the album’s narrative soul.

The album itself soared to No. 6 on the Billboard Top Pop Albums chart, a remarkable achievement for a Western concept record. But statistics only hint at its legacy. The true impact lies in how Robbins transformed dusty legends into living, breathing characters. “Saddle Tramp” is not just a song—it’s a confession whispered beneath a desert sky.

The Archetype of the Wanderer

The “saddle tramp” is a classic Western archetype: a cowboy with no permanent address, no lingering attachments, and no intention of putting down roots. He follows cattle drives, railroad lines, and seasonal work. He rides light. He leaves before dawn. And he rarely looks back.

Robbins understood this figure intimately—not merely as a romantic symbol of rugged individualism, but as a man shaped by choice and consequence. The narrator in “Saddle Tramp” embraces freedom with unwavering conviction. He answers to no boss, no lover, no hometown expectations.

Yet beneath that declaration of independence runs a current of quiet solitude.

The lyrics don’t scream regret. They don’t dramatize sorrow. Instead, they reveal acceptance—a kind of stoic acknowledgment that freedom demands payment. When the saddle tramp rides into a new town, he is unknown. When he leaves, he remains unmissed. That is both his strength and his burden.

Robbins captures this tension beautifully: the open range promises endless possibility, but it offers no lasting embrace.

Freedom’s Sweet Taste—and Its Bitter Aftertaste

At its core, “Saddle Tramp” explores a universal human conflict: the desire for self-determination versus the need for connection.

The saddle tramp’s philosophy is simple:

He goes his own way.

No one tells him what to do or say.

It’s a creed many admire. In an era increasingly bound by responsibilities, contracts, mortgages, and social expectations, the idea of shedding everything and riding toward the horizon holds undeniable allure.

But Robbins is too wise a storyteller to present freedom as purely triumphant. The song gently reminds us that independence can become isolation. The same empty horizon that represents possibility also reflects loneliness. The same quiet night that offers peace can amplify solitude.

What makes the song remarkable is its restraint. There is no melodrama. No tearful breakdown. Just a steady voice acknowledging that some roads, once chosen, cannot be retraced.

That emotional subtlety is precisely what elevates “Saddle Tramp” from a simple cowboy tune into a meditation on life choices.

Robbins’ Vocal Mastery: A Story Told in Tone

Marty Robbins possessed one of the most distinctive baritones in country music—rich, warm, and resonant with narrative authority. In “Saddle Tramp,” his voice carries the weight of lived experience. He doesn’t merely sing the character; he becomes him.

There’s a gentle weariness in his phrasing, a calm certainty that feels authentic rather than theatrical. Each line unfolds like a chapter from a leather-bound diary carried in a saddlebag.

Musically, the arrangement is classic Western minimalism:

-

Clean acoustic guitar lines

-

Subtle percussion mimicking hoofbeats

-

Spacious instrumentation that mirrors the vastness of the plains

Nothing overwhelms the story. Nothing distracts from the narrative focus. The production choices create sonic space—just as the open range creates physical space. That intentional sparseness is part of the song’s brilliance.

Robbins understood that Western storytelling depends on atmosphere. The silence between notes is just as important as the melody itself.