It starts with a breath—no, with air being shaped like clay. You hear the band lock into a gentle sway, a light percussive shuffle, and then that voice—bright, boyish, a little raspy at the edges—floating above the track like a kite caught in a friendly gust. “Itchycoo Park” is one of those records that seems to exhale summer. Even decades later, when the year on the calendar is anything but 1967, it radiates the smell of dry grass after sun, the dazzle of water through leaves, and the feeling that time itself might blur if you stare hard enough at the light.

I imagine the tape machines in London spinning, the engineers leaning forward, fingers hovering over faders and reels as the whoosh of phasing blooms across the drum kit. The effect doesn’t just color the track; it changes the weather inside the song. The Small Faces had made gritty R&B and crisp mod pop, but here they bottle a different kind of electricity—gentler, playfully altered, newly made for a youth movement staring over the fence into a wider, weirder garden.

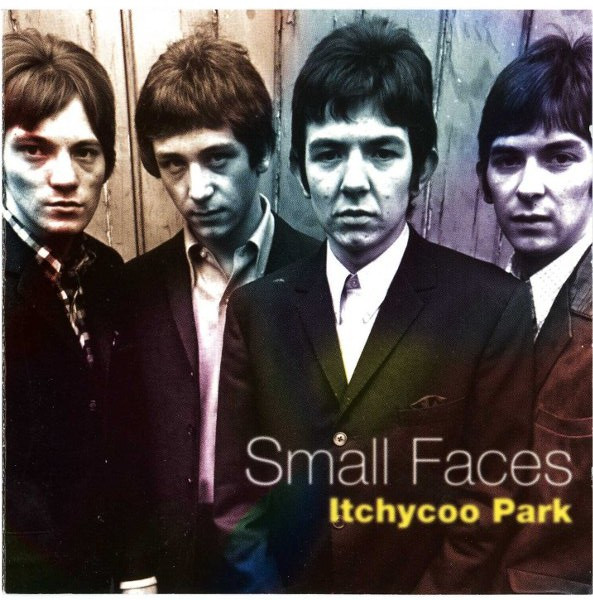

Context matters. “Itchycoo Park” arrived in 1967 on Immediate Records as a stand-alone single, written by Steve Marriott and Ronnie Lane at a moment when the group was pivoting from club-tough mod to a more adventurous, melodic sensibility. In the U.K., it lived proudly as a single; in the United States, it would be folded into the reconfigured LP There Are But Four Small Faces later that year, a kind of postcard announcing that the band’s sonic passport had been stamped for psychedelic travel. It soared into the U.K. Top 5 and crossed the Atlantic to make the U.S. Top 20 the following year—a tidy arc that tells you the record was both of its time and perfectly exportable.

The magic in “Itchycoo Park” has been overexplained and underfelt by many. Yes, the phased drums were novel; yes, the engineering trickery, reportedly pioneered in that London ecosystem by daring technicians, turned a neat studio trick into a signature texture. But the story that keeps me returning isn’t purely technical. It’s how that texture serves feeling. The drums don’t just swoosh; they breathe. They render space as a living thing, as if the park itself were sighing along.

And listen to how the arrangement builds its small world. The rhythm section moves with a limber, lightly syncopated gait—steady enough for a sing-along, loose enough to feel like afternoon nap-time tilted toward mischief. A warm Hammond-like bed of keys glows behind the voice, occasionally flaring at phrase endings with a churchy squeeze. Over that, a tidy, chiming guitar sketches the fence posts of harmony, making sure the track never drifts too far from home. Vocals are stacked with care—close, companionable, almost hand-on-shoulder close—and there’s just enough air around them to suggest an open window in the control room.

Marriott’s delivery is its own weather system. He brings a conversational ease that flirts with mischief—“what did you do there?” isn’t sung as an interrogation so much as an invitation to conspiratorial grin. He shades syllables with quick vibrato. He holds a vowel just a fraction too long, turning a simple note into a moment of shared delight. The phrasing is easygoing and proud, like a friend who can’t wait to show you a secret.

Then comes the famous part: the flanging swells, the track swims, and we are briefly underwater. The effect is tactile. It’s not psychedelia as excess or shock; it’s psychedelia as tilt, as gentle refocusing of the lens. And it’s deployed with restraint. Plenty of 1967 records were gaudier or more chemically overdetermined. “Itchycoo Park” uses its studio alchemy like a well-timed wink, a way of guiding your breathing in and out with the music.

One pleasure of this recording is its sense of scale. It never tries to be an orchestral spectacular. Instead, the band plays like a tight circle on a lawn, passing hooks around like a thermos of lemonade. The keys glow and recede. The bass nudges without nagging. The snare has a crisp little snap, softened by the phase swoop when needed. The track has headroom—literal space into which your imagination can step. That’s why it holds up in any listening environment; it tolerates being small because it already sounds like a miniature landscape.

I sometimes think of “Itchycoo Park” as a piece of music that understood childhood and young adulthood at the same time. There’s wonder, but there’s craft. There’s play, but there’s engineering. It wants you to lie down in the grass, yet it’s smart about how that grass is miked and mixed. The close-mic intimacy on the vocal makes you feel like you’re crouched near the singer, whispering back lines between takes.

Though the organ is the harmonic anchor, it’s the interplay of timbres that sells the illusion of sunlit movement. Drums flicker like light across rippled water. Background voices arrive in little clusters, never overstaying their welcome. A tambourine seems to materialize and then vanish, the way a reflection on glass does when you change your angle by a few degrees. If there’s any piano presence at all, it’s subtle—more ghost of wood and felt than declarative line—which suits the track’s modesty and keeps the harmonic palette diaphanous rather than dense.

The lyric—best thought of not as narrative but as a map of sensation—works because it withholds specifics. Many have argued about which London park inspired the title, and which plants made it “itchy,” but the record is more interested in the feeling of getting away than in the GPS coordinates of where you went. The universal floats over the particular. That’s why, half a world away and decades later, you can drive a county road at dusk and feel like the trees you pass belong to the same republic of escape described here.

Every time the chorus lands, it lifts without bluster. The harmony is a swing-set arc rather than a catapult. Think of the consonants: soft, smiling, easy to sing with your lips barely parting. The song understands euphony, not just melody. It’s a masterclass in how to make a refrain feel inevitable without rendering it inert.

“Phasing turns the air into an instrument, a musical weather system that passes right through you.”

As the record moves into its bridge and the phase effects swell, the drum hits smear in a way that invites you to lean closer. On a good pair of studio headphones you can hear the sound stage bend, then right itself, like sunlight refracting in a glass and returning to clarity after you set it down. It’s a reminder of how literal physics—air, vibration, tape-speed modulation—can conspire to feel like metaphysics when the song in the middle is sturdy enough to hold the trick.

I often test a track by playing it in three places: in a kitchen with windows open, in a car with the roadway droning underneath, and on a modest home audio setup when the house is quiet. “Itchycoo Park” thrives in all three. In the kitchen, the phased cymbals seem to dance with the clink of plates. In the car, the steady, buoyant beat matches the rhythm of signage sliding by and turns traffic into a chorus line. At night in a quiet room, the background vocals feel like friendly ghosts in the doorway, delighted you came back.

The band’s journey makes this single even sweeter. Before Immediate, they’d been hitting hard on Decca with sparkling mod stompers, and the move coincided with a fresh burst of autonomy. The writing partnership of Marriott and Lane was at a peak, and the group had grown confident enough to experiment without losing their pop instincts. If the later pastoral shimmer of “Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake” would show them building full fantasy worlds, “Itchycoo Park” is the carefree field trip that proves they can leave the city limits and still be themselves.

For all its lightness, the record is not disposable. Its central trick—the feel of the air being made musical—has been imitated endlessly. The lesson modern producers sometimes miss is proportion. The effect here serves the story. When the drums blur, your memory blurs with them. When the guitars regain their chime, you sense a smile returning to someone’s face a few inches from the mic. The production is the text, not just decoration.

Three quick vignettes, because this song keeps making new rooms:

A student in a late dorm night, exam notes scattered like confetti, puts it on to feel a simpler sky. The first chorus lifts the shoulders from their crouch. The second makes the paper mess look oddly beautiful. The song doesn’t erase stress; it reframes it as cloud cover, temporary by definition.

A parent drives a kid to practice and a sunbeam flickers between the rowhouses as the chorus arrives. The kid half-sings, half-mocks the words, and for a moment the car is both London in 1967 and a neighborhood that simply wants some fresh air.

A person who has never been to England sits on a bench after a complicated day. Earbuds in. Birds negotiating tree politics above. The phased drum wash and the friendly chords don’t explain life, but they make room for it.

The more I listen, the more I admire the rhythm section’s low-profile intelligence. Bass lines walk with just enough step, never turning the meadow into a sidewalk. The snare places accents like a friend patting your arm at the right moments. Nothing feels overdressed. That restraint is a kind of glamour too—the kind that doesn’t break a sweat.

You could call this the record where Small Faces proved the page could be turned without tearing it. The earlier punch remains; it’s simply softened by a dreamier lens. And because the lens is clean, the picture is timeless. What sounded new in 1967 now sounds fresh, which is rarer. Newness expires; freshness renews itself whenever sunlight hits it.

There’s also the way the vocal blend embodies camaraderie. The harmonies don’t grandstand. They fold in like friends chiming agreement during a good story. It creates an intimacy that suits the theme of escape. You go to the park with someone you trust. This single invites you to bring that person, even if they’re a memory you’re still making up.

One last note about how the band uses negative space. The arrangement leaves little pockets of quiet—tiny valleys between peaks—so that when the phase swell returns, it feels like a tide rolling back. That ebb-and-flow dynamic is the heartbeat of the track. It’s also the source of its replayability; your ear keeps leaning forward to catch the next inhalation.

In discussions of 1967 pop, the loudest artifacts often crowd the conversation: maximalist arrangements, studio fireworks, and headlines attached to famous names. “Itchycoo Park” humbly makes its argument in three minutes, with light in its pocket and freedom on its breath. It loses nothing by being a compact single; if anything, the brevity is part of its charm. Consider this your reminder that not every milestone needs to be a monument. Some are a sunny afternoon, perfectly mixed, that you can carry around forever.

And yes, when the chorus asks the obvious question about where someone’s been, it answers with the only destination that matters: away. That remains the most adult kind of innocence pop can offer.

If you haven’t sat with it in a while, return to it with curiosity. Let the drums blur the edges of your day, and let the keys glow like a window you forgot was there. This isn’t nostalgia as retreat; it’s craft as escape route, built by a band who knew how to keep wonder in tune.

For any reader wanting to follow its chord shapes or vocal blend more closely, it’s the rare single that rewards careful listening and casual humming alike. Study it, sing it, or simply drift with it—the record holds.

Somewhere between a lazy Sunday and a bus ride to nowhere, “Itchycoo Park” is waiting, still sunlit, still smiling.

Listening Recommendations

-

The Kinks – Waterloo Sunset — London tenderness with shimmering guitars and a river’s-eye calm, cut in the same bright year.

-

Pink Floyd – See Emily Play — Playful, compact psychedelia where studio trickery serves a candy-coated melody.

-

The Move – Flowers in the Rain — Breezy, percussive pop with late-’60s English whimsy and a crisp, windblown hook.

-

Traffic – Paper Sun — Sitar-tinged swirl and rhythmic lightness that feel like another path through the same summer.

-

The Beatles – Dear Prudence — A later, gentler trance with circular guitar figures and an invitation to open the shutters.

P.S. If you want to catch the record’s phantom details—the swell, the smear, the hushed harmonies—try one close listen on studio headphones, then one in your favorite room. And if you’re curious about how it translates to a living space, a straightforward home audio setup will let the track breathe the way it was meant to.