Few singles summarize the artistry of Motown in the mid-1960s as elegantly as “The Tracks of My Tears.” Written by Smokey Robinson, Warren “Pete” Moore, and guitarist Marv Tarplin, and released on Tamla in 1965, it’s the kind of record that feels simple at first blush—a tender confession set to an easy glide—then reveals new layers with every listen. The song’s brilliance lies in that elusive balance between poise and rawness, between pop concision and the depth you might expect from the best country ballads or classical lieder. You can hum along to the hook without effort; yet the closer you listen, the more you discover careful counterpoint in the backing vocals, lapidary guitar filigrees, and a narrator whose emotional mask is slipping line by line.

The album context: Going to a Go-Go

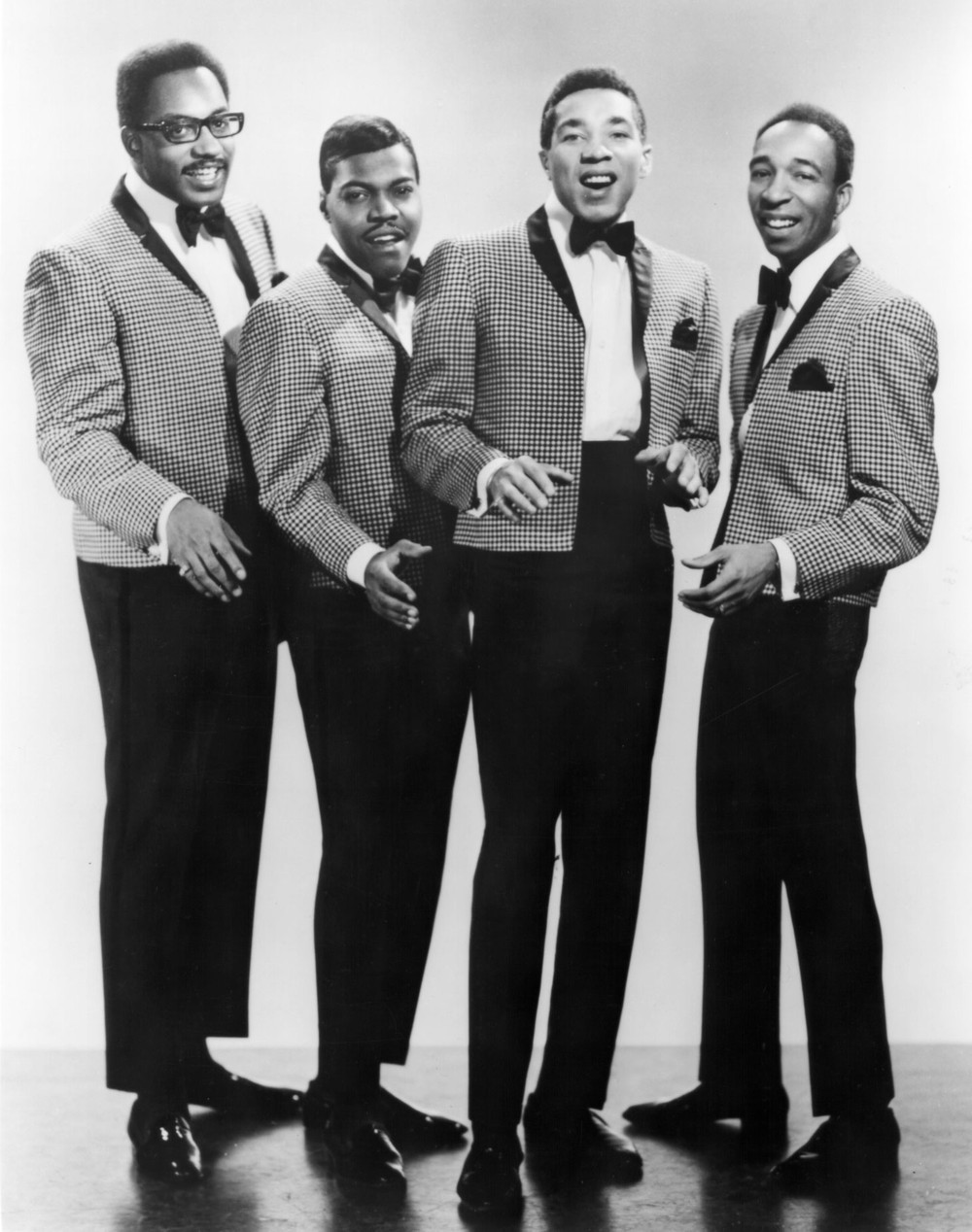

“The Tracks of My Tears” found its long-playing home on Going to a Go-Go (1965), arguably the finest Miracles album and a landmark in Motown’s golden run. The LP arrived at a moment when Smokey Robinson had fully matured as both writer and producer: melodies came unforced, arrangements served the lyric, and the group’s identity felt unmistakable even as they shared studio space with the same house musicians who powered hits for The Temptations and The Four Tops. Going to a Go-Go gathers a string of luxurious singles—“Ooo Baby Baby,” “The Tracks of My Tears,” “My Girl Has Gone,” and the effervescent title track—into one coherent statement. What binds the album is emotional range: euphoria and ache, optimism and regret, each shaded by Robinson’s elegant pen and the Miracles’ seamless blend.

Placed on this album, “Tracks” functions like a center-of-gravity. Its subject, pride with a hairline fracture, echoes the world-weary sweetness of “Ooo Baby Baby,” but the imagery is even more indelible. On an LP that celebrates dance-floor communion and neighborhood romance, here is the quiet corner at the end of the night, the unguarded admission whispered after the crowd thins. The production doesn’t announce itself; it invites you closer. That restraint, against a backdrop of other hits pushing toward brassier sonics, is part of what makes the album so compelling and the single so timeless.

Instruments and sound: the Motown chamber ensemble

The immortal opening belongs to Marv Tarplin’s guitar: a delicate, descending figure that sketches the mood before Smokey sings a word. Tarplin’s tone is clean, close-mic’d, and just bright enough to sit atop the rhythm section without cutting. He picks more than he strums, outlining chord tones and slipping in ornamental slides that suggest both assurance and vulnerability. In much the same way that a classical art song hinges on an accompanist’s sensitivity, Tarplin becomes a co-narrator, responding to and anticipating Robinson’s phrases.

Beneath that guitar is Motown’s signature engine—kick drum and snare with a satin attack, a tambourine that flashes on two and four, and a bass line that refuses to grandstand yet never stops singing. James Jamerson’s lines in this era balanced counter-melody with utility; here, the bass tends to move stepwise, supporting the chord changes with a quiet lilt that keeps the record buoyant. The drum part is spare by design: a lightly shuffled backbeat that leaves space for breath and for the painful truth in Robinson’s voice.

Keys are present but tactful. The piano doubles some rhythmic hits and fills out the harmony in the choruses; occasional organ pads poke through like gentle exhales. If strings are there, they are subtle, more implied by the vocal blend than etched into the mix. The focus remains the small-ensemble intimacy—the feel of a room rather than a grand hall—what you might call a Motown chamber group. It’s a masterclass in economy: guitar, piano, bass, drums, and hand percussion interlock like watch gears, each essential and none overbearing.

The voice and the mask

Smokey Robinson’s lead vocal is the record’s true orchestration. He begins in a conversational register, airy and confiding, then sails into a controlled falsetto on the chorus that turns grief into something weightless—hurt transfigured by artistry. He accents consonants delicately (“al-though she may be cute”), stretching vowels so that words bloom rather than merely pass. One of his gifts is dynamic phrasing: he thins the tone on the verses, thickens on the chorus, and lets particular syllables float a fraction ahead or behind the beat for emotional emphasis. If you come to this record from a classical perspective, you may hear shades of the lied tradition—the poetic persona, the double narrative of surface and subtext, the accompaniment’s role in mirroring inner weather. From the country side, the song shares the moral center of the great tear-stained ballads: the public face steady as stone, the private heart cracking underneath.

The Miracles’ backing vocals form a gentle halo around the lead. Their “oohs” and “ahhs” never crowd the lyric; they create a soft focus, like the shallow depth of field in a portrait. On the chorus, the harmonies widen slightly, lifting the hook without turning it into a shout. This restraint is crucial. Where other soul groups might lean into call-and-response theatrics, the Miracles prefer velvet. The aesthetic matches the narrative: the singer isn’t storming out of a room; he’s pretending to enjoy the party and telling you, sotto voce, that he’s dying inside.

Country storytelling, classical poise

From a country music vantage point, “The Tracks of My Tears” lives in the same emotional neighborhood as George Jones’s “She Thinks I Still Care” or Roy Orbison’s “Crying”—songs where the ego tries to hold the line while the body betrays it. You can practically imagine a pedal steel tracing the vocal line, or a fiddle doubling Tarplin’s guitar, and the story would still work because the core is universal: pride negotiating with heartbreak. In classical terms, think of how Schubert sets a simple image—the spinning wheel, a brook, a winter landscape—and lets it carry disproportionate emotional weight. Here the image is makeup masking tear trails, a metaphor so exact it feels inevitable. This cross-genre durability is why the track remains a recital piece for singers across pop, R&B, and even Americana idioms.

Structure and harmony

Harmonically, the song favors change without drama. The verse moves with gentle logic—cadences that feel earned, not engineered for surprise. The pre-chorus tightens the screws just enough to make the chorus bloom, and that chorus, crowned by the phrase “So take a good look at my face,” lands squarely on the sensation of revelation: the mask slipping in real time. Melodic contours mirror this architecture. The verses hover within a comfortable mid-range, as if the narrator is still keeping up appearances; the chorus stretches upward, the emotional tell you can’t quite hide. The resulting arc is compact and perfectly scaled, a lesson in craft for anyone who writes songs or orchestrates them for small ensembles.

Production details: air and proximity

Part of the record’s power is its engineering. There’s a cushion of room reverb but never so much that it blurs articulation. The tambourine sits in its own airy pocket, each jingle distinct. The guitar is slightly forward in the stereo field, like a confessional aside. Vocals have a hint of plate reverb that flatters Smokey’s high notes without smearing his consonants. If Motown famously chased immediacy, “Tracks” shows how they could also chase intimacy—less a dance floor, more a shared booth after midnight. From a technical standpoint, this is the kind of production that modern music streaming services still showcase gracefully; the mix translates across earbuds and living-room speakers because the arrangement isn’t frequency-bloated and the dynamics breathe.

Lyric imagery and interpretive depth

The lyric is persuasive because it’s honest about performance—how we perform being fine. “Although she may be cute, she’s just a substitute.” That admission is both unkind and vulnerable; rebound relationships often are. The song’s central image—tears leaving “tracks”—works on multiple levels: the literal marks that makeup can’t fully cover, the figurative record of grief etched into a face, even the suggestion of a railroad out of town that the singer can’t bring himself to take. The brilliance of Robinson’s writing is how little he needs to say. He chooses one vivid image, circles it with three or four verses’ worth of angles, and the audience does the rest.

As a piece of music, album, guitar, piano all converge to illuminate that image. Tarplin’s guitar paints the outline; the piano adds the soft shading; the rhythm section draws the frame; the Miracles fill in the background, a gallery of witnesses who don’t intrude. The word “tears” might be what you remember, but the delivery—notes bending at the edge of falsetto, the catch on “look”—is what breaks you.

Why it endures—and what performers can learn

What makes “The Tracks of My Tears” a singer’s singer song is the opportunity it gives for nuance. Over-sing it and you lose the point; underplay it and you miss the slow reveal. The text invites rubato, tasteful ornament, and dynamic contour—skills as relevant to a Schubert recital as to a late-night R&B set. For instrumentalists, the lesson is placement: Tarplin’s lines, Jamerson’s motion, the drummer’s restraint, the tambourine’s glint on the backbeat. Every element lands exactly where it must. If you’re arranging a cover, consider how a lightly brushed snare, a nylon-string guitar, or a chamber-string quartet might re-voice the architecture without trampling the lyric. The song is strong enough to bear cross-genre clothing; that’s rare.

From an industry lens, the record is also a reminder that timeless catalog is the backbone of music licensing. Filmmakers and series supervisors reach for songs like this to telegraph interiority with grace: a character smiling at a crowded table, the camera finding the eyes, and we hear Smokey confess to us what the scene cannot. The tune’s steady rhythmic sway and the quick recognizability of its opening guitar figure make it potent in short cues without needing the full vocal to land.

A note on performance practice

Because the arrangement is so transparent, small interpretive choices loom large. Intonation and blend in the backing parts determine whether the chorus sighs or sags; tambourine timing decides whether the groove floats or drags. Pianists often underestimate their role in recordings like this, relegated to comping and occasional arpeggios, but the piano’s job is crucial: filling harmonic midrange without crowding the guitar’s sparkle. Acoustic guitarists can study Tarplin’s balance of pick and flesh, how he leans into certain slides for emotional color rather than technical dazzle. Drummers should attend to ghost notes and the space between snare and tambourine—those micro-pockets of silence are the cushions on which the vocal rests.

Hearing it today

Heard through contemporary speakers, “The Tracks of My Tears” still sounds modern, not because it chases modernity but because sincerity, restraint, and good melody never date. If you’re coming from country, listen for the narrative honesty; if you’re steeped in classical, listen for the way melody carries subtext without ornament calling attention to itself. And if you’re simply new to Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, let this be your doorway into an album that captures their essence without a single wasted measure. Return to Going to a Go-Go as a whole—sequence matters here—and notice how “Tracks” acts as the emotional fulcrum. You emerge from it changed, as if you’ve been entrusted with a secret.

Recommended listening: songs that share the soul

If “The Tracks of My Tears” moves you, here are a few paths you might follow:

-

Smokey Robinson & The Miracles – “Ooo Baby Baby.” Another exquisitely restrained confession from the same era, with a falsetto that feels like a sigh turned into melody.

-

The Temptations – “My Girl.” Joyful on the surface, but listen to the precision of the arrangement—the same Motown attention to balance and space.

-

Marvin Gaye – “Ain’t That Peculiar.” A sharper rhythmic cut, yet the lyric dances around complicated hurt in a way that pairs beautifully with “Tracks.”

-

Roy Orbison – “Crying.” From the country-pop side, a cousin in theme: the façade collapses, and the voice soars.

-

George Jones – “She Thinks I Still Care.” Classic country stoicism fraying at the edges; the storytelling instinct is kindred.

-

Aretha Franklin – “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You).” A different temperature—volcanic, not cool—but the same honest reckoning with need and pride.

-

Dionne Warwick – “Walk On By.” Bacharach & David’s urbane ache; if you love dignified sorrow rendered with elegance, you’ll find a home here.

Any of these can serve as a companion study in how singers and bands translate interior conflict into exterior grace. They also demonstrate how a well-judged arrangement—like a finely written chamber part in classical repertoire—can turn a three-minute single into a world.

Final reflections

Great records reveal themselves on multiple timelines: instantly, in the hook you can’t shake; slowly, in the aftertaste that follows you for days. “The Tracks of My Tears” excels at both. It is immediate enough to own a jukebox and intricate enough to reward analysis from the vantage points of country storytelling and classical songcraft. Its textures—guitar whispers, tambourine shimmer, bass with a singer’s sense of line—build a home for a voice that refuses to overplay its hand. The lyric offers a single unforgettable image and trusts you to live inside it.

If you are exploring Smokey Robinson & The Miracles beyond the singles, Going to a Go-Go is mandatory listening—a cohesive statement in which this track is the spiritual centerpiece. And if you’re a performer, arranger, or producer, study how modest means can yield profound impact: a handful of instruments, a human story, and the discipline to let space speak. In that sense, the record is not just a sentimental favorite; it’s a standard, a model for how popular music can be attentive to poetry and craft without losing its warmth. Return to it when you need reminding that less really can be more, and that pop, soul, country, and classical ways of telling the truth sometimes meet in the same quiet room.

As a closing thought, treat “Tracks” as both listening pleasure and a compact lesson in arrangement. Let the piece of music, album, guitar, piano associations guide your ear: how each element contributes, how none dominates, and how the whole shimmers with a kind of humane restraint. The result is a record that not only chronicles heartbreak but dignifies it—turning private sorrow into communal art, one perfect phrase at a time.