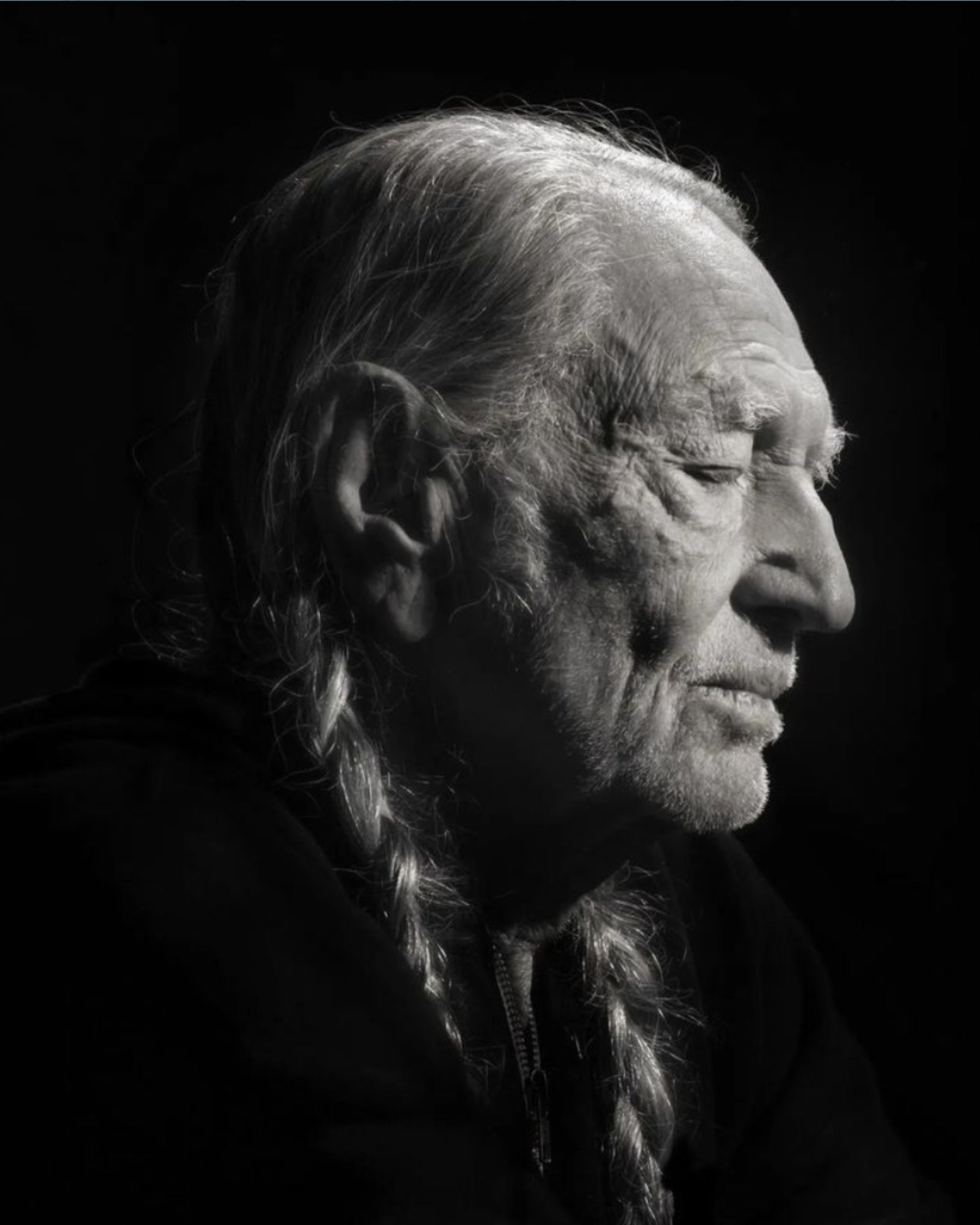

Some voices don’t just sing; they feel like a piece of home, a comforting presence that has been with us through it all. That’s the magic of Willie Nelson, an artist who has poured his entire soul into his music and shared it with the world for decades, becoming a true national treasure. Amidst the recent wave of love and well-wishes for this legend, I found myself returning to one of his most profoundly tender songs, “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground.” The track is a beautiful, gentle plea to care for a precious spirit, and it perfectly encapsulates the protective and heartfelt way the world feels about this incredible man who has given us so much joy.

There’s a hush before the first phrase lands—Tokyo’s Budokan settling into stillness, the camera easing toward a man whose voice has weathered a thousand highways. Willie Nelson leans into the microphone the way a confidant leans over a diner table at 2 a.m., close enough to spare you the performance and offer the truth instead. This is “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground,” a ballad that became a country chart-topper in 1981 after first appearing with the 1980 film Honeysuckle Rose—and in this 1984 concert, it feels less like a hit and more like a benediction, an act of care rendered in melody.

The video comes from Nelson’s Budokan show, recorded on February 23, 1984, and now widely available through the official Live at Budokan release. It’s the kind of archival document that clarifies rather than merely commemorates. The recent issue—produced by longtime bandmate Mickey Raphael—pulls you into the room, the mix framing the voice up front and the band like a soft-lamped halo around it. What was once a near-mythic tour artifact is finally heard as a cohesive concert document, not a souvenir: a portrait of Nelson and his Family Band at a poised, conversational simmer.

Context matters here. The studio version had already earned its place in the canon, climbing to the top of Billboard’s Hot Country Singles in 1981. Nelson, by then, had long since graduated from Nashville outsider to American fixture; his 1970s work proved he could fold jazz phrasings and border-town swing into country storytelling without cracking its shell. Yet at Budokan he does something subtler. He takes a song that success could have turned into memorabilia and returns it to its bare, breathing core: a goodbye that knows how to love.

The stage picture is unassuming: a semicircle of players who know each other’s reflexes, a rhythm section that moves like a single body. You can hear Bobbie Nelson’s piano—ornament rather than thesis—place gentle handholds between vocal lines. Paul English’s drums don’t so much keep time as keep vigil. Bee Spears on bass leans his notes forward, then lets them bloom; the sustain becomes a kind of margin where feeling occurs. Grady Martin’s guitar enters like a memory you didn’t know you still carried, a dusty twang with the restraint of someone who understands that echo can do more work than volume. Jody Payne doubles the human warmth on rhythm and vocal blend, while Mickey Raphael’s harmonica curls in and out of the frame, a tone poem of sighs and commas. It’s an ensemble of emanation rather than declaration, and that’s exactly how the song breathes.

What makes this performance resilient is how Nelson locates the music’s spine. His phrasing floats on the beat the way a paper lantern floats on air—never hurried, never inert. He places words a breath late, turning the delay into meaning: care takes time, and that time is audible. The vowel warmth on “angel” opens like a doorway and the consonants arrive with the tenderness of someone tucking in a child. He sings as if he’s calibrating light: a little more glow on remembrance, a little less on regret. The vibrato doesn’t argue its presence; it appears at the ends of lines like a small wave that washes what the sentence left behind.

Listen closely to the dynamics. The band rises in quarter-inch increments; you feel it more than hear it. When the harmonica shades the second refrain, it’s an intake of breath. When the guitar sketches a reply, the tone is thin on purpose, a plaintive filament that holds the lyric without burning it. There’s space in the mix—enough to hear the reverb tail of the hall, enough to appreciate how the mic captures the fricatives that “humanize” the line. We’re not in a studio; we’re inside a room where every choice has to land with a human pulse.

It helps to remember where the song came from. Written by Nelson for the Honeysuckle Rose project, the ballad rode the film’s orbit into the pop awareness of the early ’80s. But the composition itself belongs to an older contract: the exchange of care with an understanding that love, properly offered, is also the art of letting go. That the single topped the country chart is less an argument for its popularity than a clue to its clarity; the lyric speaks plainly, without metaphorical pyrotechnics, and finds its power in trust.

At Budokan, the trust is communal. Watch the way Nelson glances toward his players between phrases, or how the band anticipates his breath as much as his cue. The music is chamber-like in its attention, almost classical in how it shares an implied score. This is that rare piece of music which enlarges itself by staying small. You get the sense they could play it at festival volume and it would still land as a whisper; the emotional architecture doesn’t depend on decibels.

I find myself thinking about the timbre of Nelson’s guitar, that famously worn Martin known as Trigger. The tone is high, wiry, and declarative, with those Django-haunted runs that tumble forward like a story he can’t help but finish. Yet on this song, he resists the temptation to ornament. The short fills sit in the breath between syllables, never in competition with them. His solos are really annotations—footnotes in melodic ink.

The camera’s distance in the video (and the updated mix on the official release) lets you appreciate the band’s acoustic glue. Piano voicings arrive like gentle stitches between phrases; bass notes drop at a perfect diagonal, balancing warmth and definition. If you listen on good studio headphones, you’ll hear the slight bloom of the hall around the harmonica—just enough air to remind you this is flesh-and-bone music, not a digitally perfected sculpture.

What I love most is the humility of the tempo. It is sober without being slow, measured without stiffness. Some singers dial up the pathos; Nelson dials up the patience. He positions the song as a private conversation happening in public. Even the applause feels like eavesdroppers exhaling.

There’s a kind of moral center to his delivery. When he sings about mending and release, you believe that the speaker has done both. The phrasing is the evidence. He angles certain words downward, as if placing them carefully on a table; others he floats, as if to acknowledge their weight while refusing to add more. The discipline here is refusal—refusal to oversell, refusal to ornament grief.

“Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground” is sometimes described as a love song; I hear it as a caretaking song. Love is the medium, but caretaking is the work. The lyric doesn’t bargain for permanence. It thanks, it tends, it lets go. The Budokan performance enacts that ethic in sound. Every choice tilts toward gentleness; every instrument practices a kind of sonic hospitality.

Consider the arrangement’s edges. There’s no string section swelling toward cinematic catharsis; instead, the heat comes from quiet friction: bass against kick, guitar pick against steel, breath against reed. The absence of orchestral sweep is not a lack; it’s the point. When you remove grandeur, you can hear the grain of the voice, the micro-slides, the little catches that telemetry can chart but only feeling can interpret.

I’m struck by how the performance also reframes the idea of the road-worn troubadour. Nelson’s public image—braids, bandana, outlaw myth—could be read as style. Here, it’s context. He brings a traveler’s economy to his lines: no wasted words, no wasted notes. When Grady Martin lifts a phrase, it’s a nod from an elder who knows the value of understatement. When Bobbie Nelson leans into a grace note, it’s as if she’s setting a teacup down in the exact center of a saucer, an act of care disguised as habit.

If you came to the song through the 1981 single, the Budokan take might feel like a time capsule opened in the present tense. It clarifies how Nelson’s interpretive gifts—his rubato, his speech-like timing—can deepen with space around them. The road learns you, and you learn the road. That knowledge shows up in the rests as much as in the notes.

There’s also an engineering grace to the Live at Budokan restoration that’s worth acknowledging. The release brings fidelity without varnish, capturing the acoustic guitar’s transients and the harmonica’s reed noise with flattering honesty. You can hear how breath shapes the contours of the melody—how the arc of a line is really the arc of a lung. The result preserves the intimacy of the moment while widening its audience, the way a well-tuned home audio system can render a small trio as a living presence in your room.

A few micro-stories keep returning while I listen. One: a late drive on an unlit highway, the dashboard dials dimmed, when someone you love is three states away and you’re trying to decide whether to call now or in the morning. The band’s hush becomes your thinking space, the melody the voice that says you already know what to do.

Two: a hospital corridor at 4 a.m., vending machine coffee cooling in your hand. You’re between rooms, between updates, between versions of tomorrow. The harmonica lines don’t console exactly; they companion you. You’re not alone in the corridor anymore.

Three: a house you once shared, now emptied for the realtor’s photos. You stand in the clean echo of the living room and realize the air remembers a different shape of furniture, and the silence remembers two voices. The final chorus doesn’t judge you for feeling relief and grief in the same breath. It just gives you somewhere to place both.

I keep thinking of this as a caretaker’s anthem because of how generously it frames departure. There’s no villain here. Love, Nelson suggests, might best be measured by how well we prepare each other to leave. It’s a radical tenderness to center on a concert stage, and it depends on a band that understands implication.

If the album context is the story’s scaffolding, the performance is the house you enter. On the lineage side: the song originated on the Honeysuckle Rose soundtrack and became one of Nelson’s defining early-’80s moments; on the live side: the Budokan recording finally received an official, lovingly produced release decades later, with the Tokyo lineup named and celebrated. Knowing the facts doesn’t reduce the feeling; it protects it, giving us a frame for why this night, this room, and this band matter.

Here’s the line I keep underlining as a listener and a critic:

“Some performances don’t chase emotion—they make room for it, and then stand quietly to the side while it arrives.”

That’s the Budokan “Angel.” The melody doesn’t plead. The band doesn’t insist. Nelson narrates a love whose climax is a release rather than a capture, and the hall’s air becomes part of the arrangement—an instrument of allowance.

If you’re the kind of listener who collects artifacts, this performance is a reminder to collect meanings instead. Try putting it side by side with the studio single, or with other torch songs that favor patience over fireworks. Hear how Nelson’s phrasing toggles effortlessly between sung tone and spoken cadence, how the consonants articulate like the click of a locket closing and opening again.

And if you’re a player yourself, this is a masterclass in the power of placement. What the piano doesn’t play matters as much as what it does. What the guitar doesn’t bend tells you as much as what it bends. Space is not a lack; space is instruction.

Though this is a concert capture, the intimacy is such that you could imagine it being sung in the corner of a small café or a dark living room with the lamp dialed low. You don’t need sheet music to feel how the changes breathe beneath the lyric; you need a willingness to sit still, to let story outrun spectacle, to honor the quiet bravery of letting go.

In the end, the Budokan “Angel” reminds you that songs can be acts of service. Nelson serves the lyric; the band serves the room; the room serves the listener who needed to hear a friend say, carefully and without fuss, that love sometimes means smoothing a wing you know will carry someone away from you.

Listen again. Not for novelty, but for recognition. It’s all there—the patience, the precision, the kindness—and it keeps sounding new because the kind of courage it names never goes out of style.

Listening Recommendations

-

Willie Nelson – “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” — Similar unadorned hush; a masterclass in phrasing-as-story.

-

Willie Nelson – “Always on My Mind” — A different kind of caretaking song, regret lit by restraint rather than drama.

-

Townes Van Zandt – “If I Needed You” — Quiet devotion with acoustic grace and emotional economy.

-

Emmylou Harris – “Goodbye” — Sparse arrangement, vocal honesty, and the dignity of release.

-

George Jones – “He Stopped Loving Her Today” — Monumental grief rendered with classic country clarity.

-

Willie Nelson & Merle Haggard – “Pancho and Lefty” — Narrative balladry with a band that understands space and implication.