I remember the first time I truly heard the opening phrase of “I Got You Babe”—not just the familiar, looping refrain of a classic-rock radio staple, but the almost impossibly dense texture of that signature arrangement. It was late, windows down on an empty highway, the radio humming with a clean, almost unnaturally bright frequency. The sound felt massive, a wall of pure, shimmering optimism.

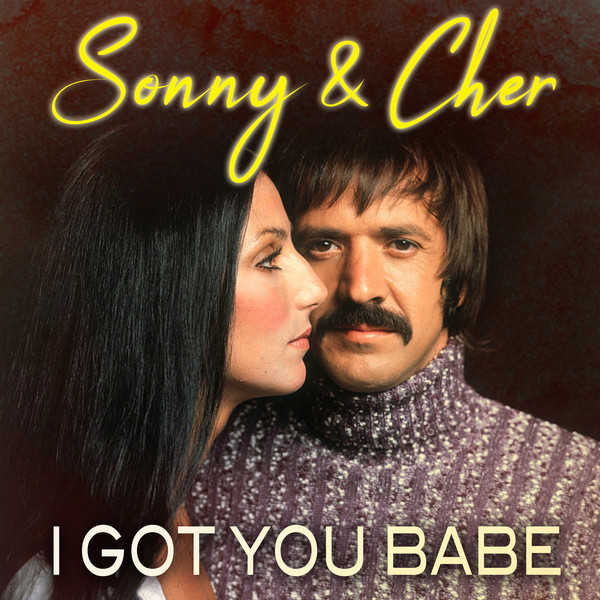

The year was 1965, and the pop landscape was a kaleidoscope of the British Invasion’s swagger, the cerebral introspection of the folk movement, and the sheer sonic spectacle of the Southern California studio wizards. Enter Sonny Bono, an ambitious songwriter and producer—an acolyte of Phil Spector, no less—and Cherilyn Sarkisian, a sixteen-year-old backup singer whose voice carried the promise of a generation. Together, as Sonny & Cher, they delivered “I Got You Babe,” a single that didn’t just climb the charts; it announced a new archetype of pop stardom: the scruffy, slightly bohemian, utterly devoted couple against the world.

The single, released on Atco/Atlantic, was a critical pivot point for both artists. Sonny had already tasted minor success, but this was the song he wrote and produced himself, born from the frustration of stalled solo efforts and written, as legend suggests, on a broken old piano in their Laurel Canyon garage. It was the centerpiece and title track of their debut album, Look at Us, and it was their manifesto. This piece of music, which Cher reportedly initially hated, became an international phenomenon, hitting the number one spot in both the US and the UK, cementing their transition from session-singer hopefuls into cultural icons.

The sound of “I Got You Babe” is a fascinating contradiction: lyrically bare and universally relatable, yet sonically intricate and deeply stylized. From the first downbeat, the arrangement—credited to Harold Battiste and executed by the legendary, uncredited session musicians known as The Wrecking Crew—is immediately captivating. It’s built on a loping, romantic waltz rhythm, a 6/8 time signature that gives the entire track a gentle, swaying forward momentum. This foundation is pure 1960s pop perfection.

The instrumentation is a clinic in texture layering. An acoustic guitar provides a clean, rhythmic strumming bedrock, keeping the folk-rock heart of the composition beating steadily. But it is immediately juxtaposed by a flurry of high-end details: the iconic, slightly reedy counter-melody played by an oboe (often misidentified as an ocarina) floats above the mix, lending a dramatic, almost cinematic quality. The drums are mixed with that familiar, Gold Star Studios crush, driving the rhythm section forward with heavy-handed reverb. You can almost feel the studio room tone on every snare hit.

Crucially, there is no featured piano riff, but a subtle, twinkling keyboard texture often fills out the mid-range and high end, a glistening layer that adds to the Spector-esque density. The whole arrangement functions like a lush, benevolent blanket, a premium audio experience designed to envelop the listener. It’s a prime example of a producer using a dense sonic palette to amplify a simple emotional truth.

And then there are the voices. Sonny’s opening verse is delivered with a slightly rough, earnest tone—the voice of the everyday guy, the underdog poet. Cher’s response is the revelation: her contralto is deep, resonant, and carries a world-weary soul far beyond her years. The exchange is structured as a dialogue, a call-and-response that frames the whole song as a shared declaration:

Sonny: “They say we’re young and we don’t know / We won’t find out until we grow.”

Cher: “Well I don’t claim to know much / But I know that I love you.”

This back-and-forth is the song’s narrative engine, a theatrical device that elevates a simple love song into a defiant social statement. It captures the moment—the rejection of adult skepticism, the purity of youth idealism—but it’s also why the song endures. Every generation feels like they’re the first to face down the cynical critics who claim their love won’t pay the rent.

“It is the sound of two outsiders carving out a protected world with nothing but four chords and an unbreakable, televised belief in one another.”

The dynamics of the track are meticulously controlled, building verse by verse toward the crescendo of the bridge, a moment of maximum harmonic and vocal intensity. Sonny and Cher finally sing in unison, their voices blending into a single, defiant blast of commitment, before the melody descends into the endlessly repeating, chanting coda: “I got you, babe.” This repetition transforms the line from a simple statement into a rhythmic mantra, fading out on a note of gentle, eternal looping that promises perpetuity.

The cultural impact was staggering. At a time when young people were looking for authenticity, they found it in this strikingly dressed, shaggy-haired duo who looked like they’d just stepped out of a Greenwich Village coffee shop and into a massive recording studio. The song bridged the folk scene’s sincerity with the Top 40’s grandeur, making it digestible—and necessary—for a vast audience.

Today, half a century later, the song’s placement in cultural touchstones like Groundhog Day—where Bill Murray’s cynical protagonist is endlessly, maddeningly awakened by its relentlessly cheerful hook—is another testament to its staying power. That cheerful, inevitable quality of the track speaks to its deep embedding in our collective consciousness. It’s an auditory certainty, the first duet on so many mixtapes, the simple sheet music for a relationship’s start. This wasn’t just a hit song; it was a cultural accessory, a uniform for the young and restless.

For critics, the temptation is always to dissect, to weigh the influences, to judge the simplicity of the lyrics. But to do so misses the point. “I Got You Babe” is a magical transmission of pure sentiment wrapped in a luxurious pop coating. It’s the perfect sonic encapsulation of two people who chose each other over everything else. We don’t just listen to the song; we listen to the contract they signed, a promise sealed with a reverb-heavy oboe and a shared microphone.

The track’s legacy invites a pause, a moment to reconsider the simple power of a declaration. Put on your studio headphones, let the waltz rhythm begin, and try to remember what it feels like to be so utterly, defiantly sure of one single, essential person.

Listening Recommendations (If ‘I Got You Babe’ Is Your Anthem)

- The Righteous Brothers – “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin'” (1964): For the blueprint of the ‘Wall of Sound’ drama and Spector-level sonic ambition that directly informed Sonny’s production style.

- Bob Dylan – “It Ain’t Me Babe” (1964): The direct folk inspiration and thematic counterpoint to Sonny’s reply; two sides of the early-to-mid-’60s youth dialogue.

- The Turtles – “Happy Together” (1967): Shares the same effervescent, underdog-optimism about a relationship triumphing over adversity, wrapped in lush pop production.

- The Mamas & the Papas – “Dedicated to the One I Love” (1967): Captures a similar sense of intimate folk-rock harmony and devotional lyrical simplicity.

- Cher – “Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)” (1966): Another Sonny Bono composition demonstrating Cher’s powerful, dramatic solo voice in a sparse, cinematic arrangement.