The recording studio air on December 13, 1966, must have been thick with the scent of coffee, cigarettes, and the quiet, focused energy of Los Angeles’s finest session players. This was Gold Star Studios, the echo chamber of Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound—a fitting birthplace for a song about history repeating itself. Sonny Bono, songwriter and producer, was laying down a track for his duo with Cher, a subtle piece of pop-rock philosophy titled “The Beat Goes On.”

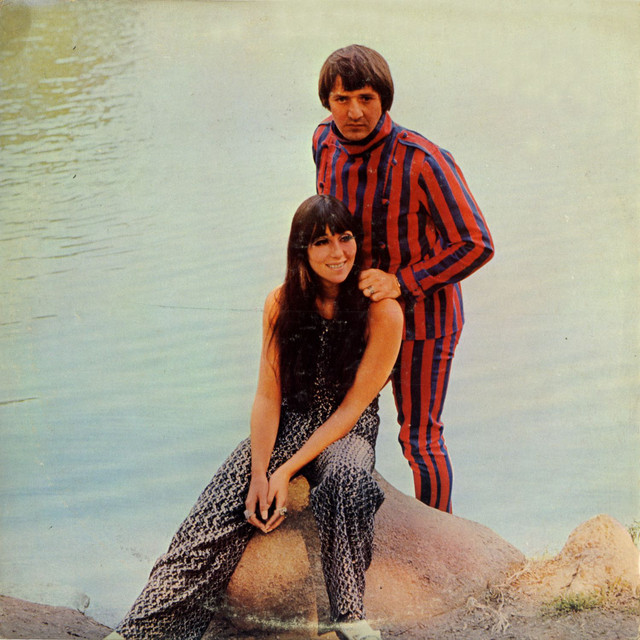

It was a crucial juncture in the Sonny & Cher story. After the global, folk-pop explosion of “I Got You Babe” in 1965, the duo had successfully maintained a high profile, transitioning from shaggy bohemian chic to mainstream television glamour. However, 1967 saw them battling the shifting tides of the rock world. Their previous album, The Wondrous World of Sonny & Chér, was well-received but did not sustain the peak momentum. This new song, released on the 1967 album In Case You’re in Love, wasn’t a desperate grab for relevance; it was something far smarter: a cool, almost detached observation of the cultural machine they were a part of.

The song works because it manages to sound utterly effortless while being musically and lyrically dense. It’s a hypnotic piece of music that captures a cultural moment not by participating in the chaos, but by standing back and narrating it with a wry smile.

The Groove That Never Stops: Instrumentation and Arrangement

The immediate, defining characteristic of “The Beat Goes On” is its rhythm. It starts with a simple, unmistakable flourish: a four-note, syncopated electric bass line. This motif, reportedly improvised by the legendary Wrecking Crew bassist Carol Kaye, replaced the original walking bass line in the arrangement credited to Harold Battiste. It’s a rhythmic hook so instantly recognizable it became the foundation of the song’s DNA, propelling the track with a cyclical, unchanging groove—the perfect sonic metaphor for the lyric.

The drumming, likely provided by Jim Gordon or Hal Blaine (the Wrecking Crew was a collective, after all), is minimal but precise. It’s a steady, unfussy beat, letting the bass do the heavy lifting in terms of momentum. The acoustic guitar work is simple, providing a clean chordal structure that keeps the arrangement airy, preventing the low-end pulse from dragging. There is no heavy piano or flashy lead guitar solo; restraint is key.

The overall sound is one of polished, late-sixties Los Angeles pop—clean, clear, and perfectly engineered for AM radio. When listening on modern home audio equipment, the isolation of each element, from the woodblock-like percussion to the separation of the vocals, is remarkable. The production is a masterclass in ‘less is more,’ allowing Sonny’s clever wordplay and Cher’s unique vocal texture to come forward.

Voice and Character: The Duo as Narrators

Cher’s voice, distinctively deep and slightly world-weary, delivers the main verses. She sounds like a knowing, slightly bored narrator, chronicling the rise and fall of trends: “The Charleston was once the rage, uh huh / History has turned a page, uh huh.” Her deadpan delivery sells the central thesis: nothing ever truly changes, only the faces and fashions.

Sonny’s contribution is the connective tissue. He sings the choruses and provides the simple, slightly off-key vocal punctuation—the iconic “Da-de-da-de-dee, la-de-da-de-da”—and the final, echoing call of the title. His voice, often overshadowed by Cher’s power, is essential here, grounding the track in an everyman earnestness that contrasts with Cher’s glamorous detachment. The interplay between them isn’t a traditional harmony, but a conversational duet, embodying the song’s theme of continuity.

“The power of ‘The Beat Goes On’ is not in its volume, but in its inexorable, cool-headed recognition that all drama eventually becomes background noise.”

The lyrics themselves are a journalistic snapshot of the mid-sixties. Sonny Bono references everything from sheet music to the “Mini-skirt’s the current thing,” and the “teenybopper is our newborn king.” He directly addresses the fleeting nature of pop culture, while simultaneously creating a piece of culture that would, ironically, endure. It’s a brilliant meta-commentary, acknowledging that even their celebrity, post-“I Got You Babe,” was a passing phase.

The Eternal Cycle: Why the Beat Endures

“The Beat Goes On” is not merely a nostalgia trip; it is a structural statement on human experience. Every generation experiences its own version of the Charleston, the mini-skirt, and the teenybopper king. This cyclical quality makes the song immune to true aging.

Think of a young person today, scrolling through endless content. The song’s central theme—that all the furious energy and innovation of a moment will eventually settle into background rhythm—is more relevant than ever. What is a viral trend but the latest version of the Charleston, replaced a week later by the next? The beat keeps pounding, and we keep dancing to the new, brief craze, while the underlying pulse remains constant.

I recently found myself humming that bass line while waiting for a late-night train, watching the city’s frantic, illuminated energy pass me by. The rhythm became a kind of mantra, a sonic filter for the urban rush. It felt simultaneously vintage and ultra-modern, proving that its message transcends the specifics of 1967. This piece of music has become a self-fulfilling prophecy: a song about impermanence that achieved permanence. It’s a testament to Sonny Bono’s unexpected genius—a songwriter often viewed through a simpler lens, who created a work of deep, understated sociological pop.

Listening Recommendations: Songs of Rhythmic Hooks and Cultural Commentary

- Love – “7 and 7 Is” (1966): Shares a similar breathless, snapshot quality in its lyrics, though delivered with much more psychedelic aggression.

- Booker T. & The M.G.’s – “Green Onions” (1962): A masterclass in rhythmic simplicity and instrumental cool, built on an iconic organ and bass riff, much like the Sonny & Cher track.

- Nancy Sinatra – “Sugar Town” (1966): Another Sonny Bono composition from the era, utilizing a slightly spoken-word delivery over a similarly cool, sophisticated pop arrangement.

- Talking Heads – “Once in a Lifetime” (1980): A later-era song that shares the theme of detached, rhythmic observation about the passage of life and cultural moments.

- Lou Reed – “Walk on the Wild Side” (1972): Uses a distinct, iconic bass line and a conversational, narrative vocal to chronicle a series of cultural characters and social changes.

- Beck – “Where It’s At” (1996): An excellent example of modern pop built around a classic rhythmic sample and a lyrical celebration of ephemeral trends and old-school cool.