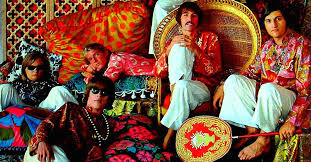

The air was thick with something electric in 1967. It was a summer—and then a fall—of transition, a head-rush of color saturating everything from fashion to film, and especially to the pop charts. Against this vibrant, sometimes chaotic backdrop, a sound emerged from the Los Angeles scene that was both perfectly timely and utterly accidental: “Incense & Peppermints” by Strawberry Alarm Clock.

I first encountered this piece of music not on some crackly AM radio dial, but through a cheap, buzzing TV speaker, soundtracking a hazy, mid-century movie scene. It was a sonic kaleidoscope that demanded to be heard again, a track that felt less like a meticulously planned single and more like a glorious studio experiment caught on tape. Decades later, with the benefit of hindsight and a good pair of studio headphones, the story of its creation—and the song’s enduring sonic power—is what truly captures the imagination.

This single, the anchor of the band’s debut album of the same name, would become the group’s defining moment, an unexpected chart-topper that reached the peak position on the Billboard Hot 100. It remains one of the most wonderfully bizarre artefacts of the late-sixties psychedelic surge. Released on Uni Records and produced by Frank Slay and Bill Holmes, the track’s success was as much a result of happenstance as it was of musical inspiration, setting the band’s career arc—brief, brilliant, and tumultuous—in stone right from the start.

The Mystery in the Mix: Sound and Instrumentation

Listening today, the arrangement of “Incense & Peppermints” is a study in restrained psychedelia, where every sonic element seems to drift and intertwine. The track famously began as an instrumental piece conceived primarily by keyboardist Mark Weitz and guitarist Ed King (who would later find greater renown with Lynyrd Skynyrd). It’s this underlying musicality that gives the final product its strange, driving cohesion.

The song is defined by the swirling, almost liquid texture of Mark Weitz’s Farfisa organ. It’s not the brutish, blues-rock Hammond roar favored by other bands of the era, but a lighter, more ethereal timbre, lending the whole sound a dreamy, hallucinatory sheen. The bass line, which many sources note was laid down by George Bunnell—though not an official member at the time of the recording—provides a nimble, melodic foundation, moving independently of the kick drum pattern and giving the track a floating, propulsive groove.

Ed King’s lead guitar work is equally distinctive. Instead of a typical fuzz-drenched solo, he weaves a high, chiming counter-melody through the verse, utilizing a vibrato that sounds less like a blues affectation and more like a shimmer of heat rising from the asphalt. The rhythm section is crisp, with an insistent hi-hat providing a tight, almost garage-rock energy beneath the haze.

The legendary drama centers on the vocals. The band’s own singers were reportedly unable to nail the melody, leading producer Frank Slay to choose an impromptu vocalist: 16-year-old Greg Munford, a friend of the band who was present at the session. Munford’s delivery is a detached, slightly bored counterpoint to the instrumental ecstasy, his voice double-tracked and bathed in reverb, reciting lyrics officially credited to John S. Carter and Tim Gilbert—a decision that caused significant strife and denied Weitz and King songwriting credit for the underlying music.

“The track is a perfect paradox: a controlled, complex psychedelic dream with a vocal line that sounds like an overheard, nonchalant pronouncement.”

The song’s dynamics build and recede subtly. The verses are close-mic’d and intimate, drawing the listener in to catch the cryptic lyrics. Then, the chorus bursts open with bright, multi-part harmonies from the band members, a momentary catharsis before sinking back into the swirling, circular organ motif. It’s a masterful economy of sound, especially for a band still finding its footing. The whole thing barely cracks the three-minute mark, yet it contains the expansive scope of a much longer work.

Context and the Cultural Moment

“Incense & Peppermints” arrived during a moment of profound cultural and sonic upheaval. The Summer of Love was peaking, and the music industry was desperately trying to bottle the essence of the new counterculture. Strawberry Alarm Clock, initially known as Thee Sixpence, found themselves at the epicenter of this shift, signing with Uni, a subsidiary of MCA.

The track’s success was not immediate. Initially relegated to the B-side of the single “The Birdman of Alkatrash,” it was savvy local radio DJs, recognizing the singular power of the hook, who flipped the record and created the demand. This organic groundswell is a charming anecdote, reminding us that sometimes the best artistic choices are driven by the listeners, not the labels.

The group’s name change, from the relatively staid Thee Sixpence to the whimsically evocative Strawberry Alarm Clock, perfectly encapsulated their sound. It spoke to the surreal, slightly off-kilter nature of their art. The song, with its philosophical, almost absurdist lines about beatniks, politics, and the ‘yardstick for lunatics,’ resonated deeply with a generation questioning established norms. The inclusion of the track in the 1968 counterculture film Psych-Out further cemented its place as a touchstone of the era.

Beyond the Farfisa, the sparse use of piano—often doubled with the harpsichord or organ to add a brittle attack to certain chords—shows an underlying awareness of baroque-pop sensibilities, subtly blending the acid-tinged West Coast sound with more traditional keyboard textures. This sophisticated layering, despite the raw energy of the band’s initial jam, is what gives the final mix its compelling depth. For those currently taking guitar lessons, studying Ed King’s counter-melodies here is a fantastic exercise in adding dimension to a rock song without resorting to typical soloing theatrics. It’s a testament to the power of a simple, repeated figure when played with immaculate tone.

The band struggled to replicate this success, often battling internal conflicts and managerial missteps. Their subsequent singles and albums, while containing moments of brilliance, never again achieved the confluence of sound, timing, and chart dominance that defined their debut. “Incense & Peppermints” thus stands as a glorious, slightly tragic monument: a peak they reached almost by accident, and never quite found the path back to.

It’s a story we see echoed across the history of pop music—a flash-in-the-pan brilliance fueled by a perfect storm of talent, tension, and studio oversight. But the confusion, the uncredited vocalist, and the songwriting disputes simply add to the song’s mystique. It is a perfect, flawed diamond of its time. I find myself revisiting it every few months, letting the organ swirl and the vocals whisper, trying to decipher the delicious ambiguity at its core. It never fails to deliver that same cinematic, sensory high. It’s a song that proves that sometimes, the most enduring art is born from the messiest of circumstances.

Listening Recommendations

- The Electric Prunes – I Had Too Much to Dream (Last Night): For the immediate, fuzzed-out garage-psych energy and studio effects.

- The Chocolate Watchband – Let’s Talk About Girls: Shares a similar blend of tight, aggressive rock and psychedelic pop sensibility.

- The Left Banke – Walk Away Renée: An adjacent mood, demonstrating the successful fusion of baroque keyboard arrangements with pop structure.

- The Association – Never My Love: Offers the same West Coast sunshine-pop harmonies and intricate melodic layering, albeit in a smoother context.

- The Doors – Break On Through (To the Other Side): Presents a comparable organ-and-guitar driven psychedelic rock that hit the charts around the same time.

- The Millennium – 5 A.M.: Exemplifies the late-60s penchant for studio-polished, melodic acid-pop with ethereal vocals.