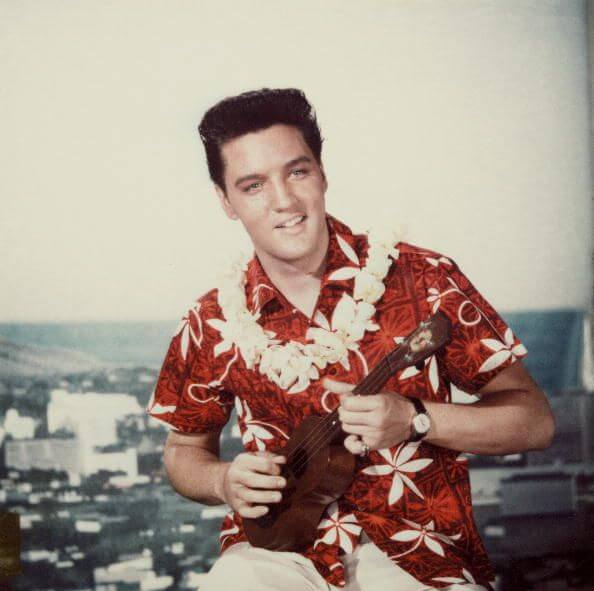

The year is 1957. The sound of a teenage revolution, catalyzed just two years prior by a Memphis boy and a handful of Sun Records sides, is now being polished, packaged, and projected onto silver screens across the nation. Elvis Presley, the symbol of raw, hip-shaking rebellion, was already pivoting. It was a pivot not of desertion, but of expansion. He was moving from regional menace to national icon, a process requiring songs that could both appease the moral guardians and electrify the burgeoning youth market.

This is the strange, wonderful crucible from which “(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear” emerged. Released in June of that landmark year, it wasn’t merely a single; it was a Trojan horse for the Loving You soundtrack, Presley’s second motion picture. It was a calculated, brilliant move by Colonel Tom Parker and RCA Victor: maximize the music’s impact by releasing the lead song weeks before the film’s July premiere. It paid off handsomely, delivering one of The King’s most commercially successful singles. But its legacy is more complicated than mere sales figures.

The Grin and The Groove: Context in the Arc of The King

To understand this simple, fast-paced piece of music, you must place it correctly in the Elvis timeline. This was the moment directly following the explosive success of “All Shook Up” and preceding the iconic grit of “Jailhouse Rock.” Elvis was at the absolute apex of his initial, raw, and transformative phase, yet he was being directed increasingly toward the perceived safety of Hollywood. Loving You was the first feature designed to showcase his talents fully, and the soundtrack—largely cut during sessions at Radio Recorders in Hollywood—blended his signature rockabilly ensemble with a more cinematic, pop-aware sheen.

The producer credit for the song is reliably attributed to Walter Scharf, alongside Steve Sholes, the RCA A&R man who had signed Presley. Scharf was a film composer and arranger, and his presence speaks volumes about the track’s intent. Where the Sun recordings had an accidental, hot-rod ferocity, the Hollywood sessions introduced a conscious layering of sound. This piece of music needed to feel big, clean, and ready for a wide audience without sacrificing the essential rock ‘n’ roll pulse.

The rhythm section on “Teddy Bear” is the indispensable engine: Scotty Moore on guitar, Bill Black on upright bass, and D.J. Fontana on drums. The track opens with a distinctive, almost comical bass-line—a rapid-fire, slightly rubbery riff from Black that gives the song its immediately infectious, swinging rockabilly gait. Fontana’s drums keep a crisp, driving beat, a blend of snap and swing that is the bedrock of early rock. Moore’s electric guitar work, though brief, is instantly recognizable, providing sharp, clean, cutting fills between Elvis’s vocal phrases, adding a necessary punctuation of pure rock energy.

A Whisper of Plush and Power

The sound of the recording is surprisingly intimate for a chart-topper destined for cinema speakers. Elvis’s vocal is forward, close-mic’d, and full of his characteristic, charmingly exaggerated drawl. He’s not shouting, he’s cooing—a masterful display of his ability to pivot from the growling menace of a track like “Hound Dog” to a playful, almost submissive flirtation. The vulnerability is the trick. He plays the simple lyrics—a plea to be a cuddly toy, to be led around on a chain—with a knowing wink.

What truly elevates the piece is the sophisticated vocal arrangement, courtesy of The Jordanaires. They are not merely providing backup; their “ooh-wah” harmonies and tightly syncopated responses are a foundational element of the structure. Their voices weave around Elvis’s lead, adding a smooth, collegiate-pop texture that softened the edges of the rock and roll attack. This contrast—Elvis’s rockabilly swagger against the Jordanaires’ refined close-harmony—is what made the record work for both the youth who craved his dangerous energy and the adults who appreciated a good, clean tune.

“It is a song about surrendering a certain kind of power in exchange for a pure, simple affection, and the music reflects that duality with surprising cleverness.”

There is an uncredited piano player on the track, reportedly Dudley Brooks, though details remain debated among session historians. Regardless of the individual, the piano’s role is essential. It provides a bright, boogie-woogie texture, subtle but present, locking in with the drums and bass to propel the whole thing forward. If you listen closely on a good premium audio system, you can hear its distinct, rolling chords tucked into the mix, a constant, joyful rumble. It’s the sonic equivalent of a smile.

The song’s brevity, clocking in at under two minutes, is another key to its perpetual charm. It’s a shot of adrenaline and affection, over before it can wear out its welcome. That economy of expression is a lesson that many contemporary songwriters could learn. The whole album’s music was designed to be consumed quickly and repeatedly, leaving the listener energized and wanting more.

The Little Bear Who Roared

In a cultural moment when young men were expected to be stoic or swaggering, this song allowed Elvis to embody a softer, more devoted masculinity. It was an image that his management shrewdly cultivated, particularly as his stardom moved from the stage to the screen. Imagine a small-town jukebox in 1957: a teenage girl is spinning this single, dreaming of a boy who is tough enough to rock, but tender enough to want to be her teddy bear.

My own memory of encountering this song wasn’t in a cinema, but years later, studying old tapes. I was struck by the confidence in its silliness. It’s an easy listen, but not a simple one. The rhythmic complexity created by the interplay of Moore’s guitar licks and Black’s driving bass is pure genius. If you’re a musician looking to understand the bedrock of 50s rhythm, acquiring the sheet music for the rhythm section parts of this era is an education in itself. It demonstrates how just three instruments, played with that kind of feel, can create a sound that fills a room and defined a generation.

This lighthearted approach was Elvis’s genius move. By embracing the absurdity of the lyrics, he disarmed his critics while delivering a rock performance that was undeniably vibrant. It was a track that reassured parents while still making their daughters swoon. That tension—the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll asking to be put on a chain—is the heart of its enduring appeal. It’s not the most profound cut in his catalogue, but it is perhaps one of his most perfectly executed pop moments. It earned its spot at the top of the charts for multiple weeks across the Pop, R&B, and Country listings, a testament to its broad and irresistible cross-genre appeal.

Ultimately, “(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear” is not about the bear itself. It’s about the permission to be adored, to be cherished, and for Elvis, to be a movie star. It’s a short, sweet masterclass in pop-rock delivery, a velvet paw delivering a rock-and-roll scratch. Give it a fresh, serious listen. You might be surprised by the complexity hidden beneath the cuddly surface.

Listening Recommendations

- Elvis Presley – “All Shook Up” (1957): Shares a similar quick-tempo, playful rockabilly energy and sense of vocal swagger.

- Buddy Holly – “Peggy Sue” (1957): Another prime example of early rock ‘n’ roll where a lighthearted premise supports an innovative, driving rhythm section.

- Jerry Lee Lewis – “Great Balls of Fire” (1957): Captures the same breakneck tempo and unbridled, slightly manic energy of 1957’s most successful rock hits.

- Fats Domino – “Blueberry Hill” (1956): Offers a counterpoint in the era’s popular music, showing a similar blend of intimate vocal charm and a solid, rolling rhythm groove.

- Little Richard – “Good Golly Miss Molly” (1958): A high-octane track that, like “Teddy Bear,” uses simple, catchy lyrics to deliver an unforgettable rock and roll punch.