There are moments in popular music history that are less about calculated genius and more about serendipity, a happy accident captured on tape just before the clock runs out. The opening of The Beatles’ 1964 single, “I Feel Fine,” is one such moment. It’s not a drum fill, or a chord, or a lyrical hook; it’s a sustained, resonant whine—the sound of a guitar leaning against an amplifier, achieving self-oscillation. Pure feedback.

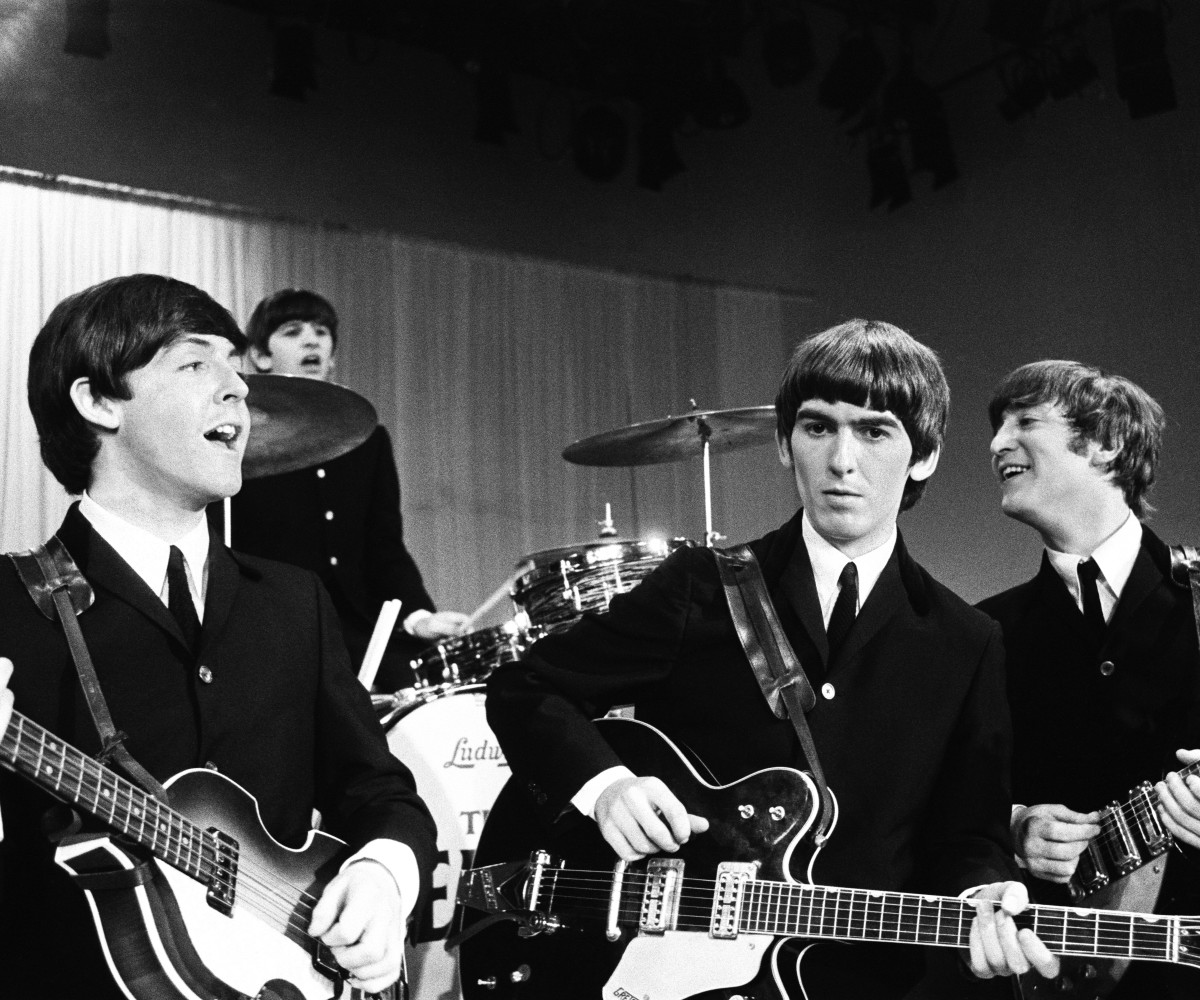

The date was October 18, 1964, a marathon nine-hour session at Abbey Road. The group was scrambling to finish material for their fourth British album, Beatles for Sale, but this track, written primarily by John Lennon, was intended as a standalone single. George Martin, the meticulous producer, and the studio engineers must have initially recoiled at the squeal. Feedback was noise; feedback was unprofessional; feedback was what you swiftly eliminated.

Yet, John Lennon, always the sonic iconoclast, heard potential in the controlled chaos. “Can we have that on the record?” he reportedly asked, recognizing a revolutionary musical texture where others heard an error. The Beatles, already conquering the world, were now subtly rewriting the rules of the recording studio, transforming an unwanted artifact of volume into the very DNA of a commercially successful piece of music.

Context: The End of Beatlemania’s First Act

“I Feel Fine” landed right at the end of what we now consider the band’s initial, frantic, Mop-Top phase. 1964 had been a year of unprecedented global domination—the American breakthrough on The Ed Sullivan Show, an unprecedented string of chart-toppers, and the release of their first film, A Hard Day’s Night. This song, released in November 1964, was the capstone. It was not included on the British Beatles for Sale album, but rather, was positioned as a powerful, non-stop momentum single, a statement of unwavering confidence.

The song’s lyric is simple, perhaps even disposable, but it perfectly fits the theme of the sound: pure, unadulterated happiness. “Baby’s good to me, you know / She’s happy as can be, you know / She said so / I’m in love with her and I feel fine.” The lyrical content is almost secondary to the infectious, driving rhythm—a feeling, more than a story.

Lennon and McCartney, credited as the writers, were moving from simple rock-and-roll structures toward a greater sophistication, but they hadn’t lost their instinct for a perfect two-minute pop blast. This track represents the moment they learned they could inject experimental grit without sacrificing commercial sheen.

The Sound of the Drive: Riff, Rhythm, and Arrangement

The actual song begins not with the scream of the amp, but with one of John Lennon’s most indelible guitar riffs. It’s a descending, arpeggiated figure in D, C, and G major that provides the foundation for the entire track. This riff, which Lennon reportedly devised while working on the Beatles for Sale track “Eight Days a Week,” gives the song a kinetic energy—it pulses and churns, instantly demanding attention.

Ringo Starr’s drumming is subtle yet complex, incorporating a Latin-tinged rhythm—a double-time hi-hat feel that lends the entire track a dancing, slightly bouncy momentum. It’s the kind of drumming that sounds simple but is devilishly hard to copy; it pushes the tempo without sounding frantic. Paul McCartney’s bassline locks into this groove, delivering a powerful, driving melodic force typical of his work in this era.

The instrumentation is classic four-piece rock, but George Harrison’s lead guitar is noteworthy. He essentially mimics the main Lennon riff during the verses, but his solo section is a layered moment of studio craft. It features two guitar parts: a backing rhythm track and a main, overdubbed solo that is almost country in its clean, sharp attack and phrasing. There is no piano or other orchestral element here; the focus is entirely on the grit and clarity of the core band, a perfect showcase for a modern listening experience using studio headphones.

The raw energy of the performance is palpable. This is The Beatles not yet wrapped in the heavy overcoats of psychedelia, but stripped down, lean, and utterly confident in their rock and roll foundation.

Innovation as Accident: The Feedback Legacy

The feedback intro is what transforms this from a great pop song into a foundational text of rock innovation. Lennon famously credited himself and The Beatles with being the first to intentionally commit feedback to commercial vinyl. Whether it was a complete accident, as Paul McCartney has often recounted, or a controlled experiment derived from live playing, the decision to leave it in was the radical act. It was a conscious blurring of the line between studio “perfection” and raw, abrasive texture.

This single note, this sustained electronic howl, became a secret key for future generations. It opened the door for The Who’s explosive live destruction, for Jimi Hendrix’s controlled sonic violence, and for every band that would later treat their instruments not just as tools of melody, but as generators of pure sound and noise.

It is a microcosm of the revolutionary shift happening in popular music. The Beatles were not just writing catchy tunes; they were actively pioneering the capabilities of the four-track tape machine, working alongside George Martin and his engineers to push beyond the conventions of mid-century pop recording. They demonstrated to the world that the studio itself was an instrument, ready to be wielded with irreverent purpose.

“The true lesson of ‘I Feel Fine’ is that sometimes, the greatest leaps in musical innovation are found not in the grand composition, but in the decision to celebrate a sonic mistake.”

That opening sound, brief as it is, forces the listener to recalibrate expectations. It prepares the ear for a piece of music that is both deeply familiar in its rock structure and startlingly new in its texture. It is a moment of pure, raw electricity that is both the past and the future of rock and roll crammed into a single, defiant note. To listen to it today is to understand that the foundations of the sonic landscape we now take for granted—from garage rock to noise rock—are laid right here, in a simple declaration of joy.

Listening Recommendations: Songs of Riff, Rock, and Innovation

- The Kinks – “You Really Got Me” (1964): Features a similarly foundational, driving guitar riff that defined the sound of 1964 rock and roll.

- The Who – “My Generation” (1965): Shares the same raw, aggressive energy and attitude, often culminating in an explosive, feedback-laden conclusion.

- The Rolling Stones – “Satisfaction” (1965): Built around another instantly recognizable, simple yet utterly commanding central guitar riff.

- Chuck Berry – “Roll Over Beethoven” (1956): The blueprint for the riff-driven, three-chord rock-and-roll that directly influenced The Beatles’ energy on this track.

- Bobby Parker – “Watch Your Step” (1961): The rhythm and blues track that reportedly provided the direct inspiration for Lennon’s signature arpeggiated riff.

- Jimi Hendrix Experience – “Foxy Lady” (1967): A later masterclass in the deliberate and creative use of controlled guitar feedback as a core element of the song’s texture.