The fog of a late October afternoon settles thick over the streets of London. Inside Studio Two at EMI Studios, Abbey Road, the air is heavy with cigarette smoke, cheap tea, and the residue of a frantic recording schedule. It is 1964. The Beatles, having already released two albums and two massive singles that year, are scrambling to deliver a new song amidst the sessions for their forthcoming Beatles for Sale album. They are exhausted, touring constantly, yet still driven by an almost manic creative energy. This is the pressurized atmosphere that gave birth to “I Feel Fine”—a track that, while seemingly straightforward, carries the silent thunder of a true sonic revolution.

It’s impossible to hear the song without immediately confronting its opening: a deep, wavering, almost monastic hum that swells for a second before being rudely cut off by the arrival of the main riff. This, of course, is the sound of deliberate guitar feedback—a sound that was, at the time, considered an error, an unprofessional blight on the recording process. Producer George Martin, along with engineers like Norman Smith, was working within the strict, almost classical parameters of EMI’s studio orthodoxy. Yet, John Lennon, always the playful anarchist, had stumbled upon the magic of the sustained, controlled squeal.

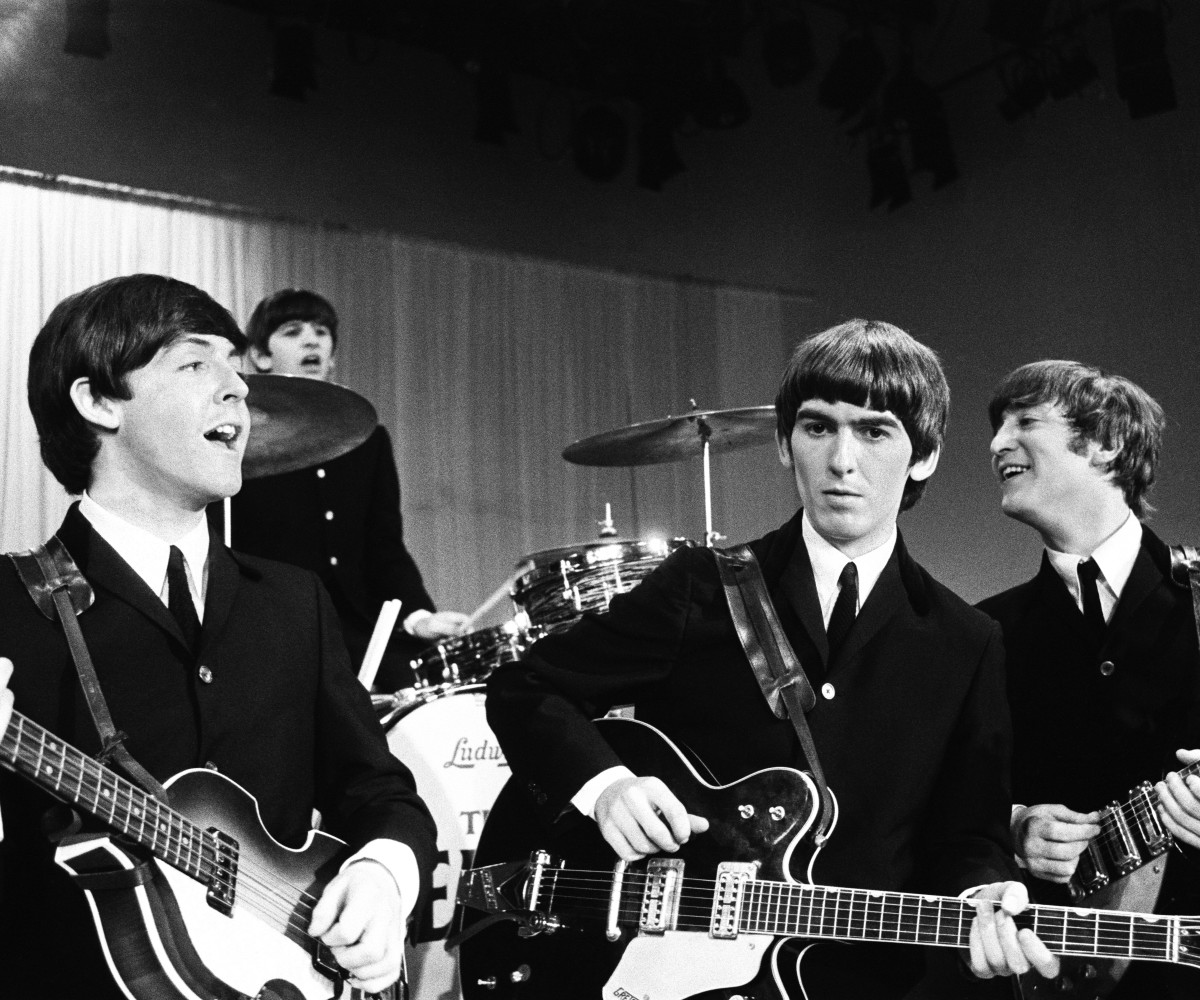

Paul McCartney reports the moment with a charming casualness: Lennon leaned his semi-acoustic Gibson J-160E against an amplifier, and the resulting harmonic wail hung in the air. That they captured it, and more importantly, chose to keep it as the very first note of a future global number one, is a statement. It was a subtle, almost secret act of rebellion. They were taking the ‘mistakes’ of high-volume rock and roll and stamping them, officially, onto vinyl. It wasn’t just noise; it was an artistic decision that pushed the boundaries of what a commercial piece of music could contain.

The song itself, primarily a John Lennon composition, is a masterclass in economy and drive. It is a confident, riff-based rocker, a clear evolution from the more straightforward pop structures of their earlier hits. The central riff, reportedly inspired by the rhythm and blues of Bobby Parker’s “Watch Your Step,” is muscular and indelible. It anchors the entire structure, appearing at the top, weaving through the verses, and returning triumphantly for the solo. This riff-centric approach, which Lennon was reportedly obsessed with applying to several tracks during this era, would become a foundation of 1960s rock.

Once the feedback is clipped, the track explodes into life. Ringo Starr’s drumming here is crucial and frequently underrated. He uses a driving, almost Latin-influenced beat (reportedly a nod to Ray Charles’s “What’d I Say”) in the verses, centering around the ride cymbal before shifting to the tight, explosive crash of the snare and tom-toms for the chorus. This dynamic contrast provides the song’s propulsion. The sound is dry and immediate; the drums feel close-mic’d, lacking the expansive reverb of some later album tracks. It’s raw, energetic, and perfectly framed by the rhythm section.

McCartney’s bassline doesn’t just hold the bottom end; it dances with the main riff, a playful counterpoint that showcases his melodic sensibility even within a three-chord rock song. The vocal delivery is classic Lennon—brash, charmingly simple, and brimming with unassailable joy. He is utterly convincing when he sings, “I’m in love with her and I feel fine.” The harmony, a familiar McCartney weave, lifts the chorus, giving the whole affair a buoyant pop sheen that tempers the grit of the underlying rock structure.

The guitar solo, played by George Harrison, is a succinct burst of energy. It’s short, bright, and utilizes a simple double-tracked effect that gives it an almost otherworldly, shimmering quality. It’s not flashy, but it serves the song’s emotional goal perfectly: an expression of pure, unadulterated happiness. The textures here—the sharp attack of the electric guitar, the steady thrum of the bass, the crystalline shimmer of the harmony vocals—are rendered with a startling clarity that speaks to the emerging quality of mid-60s Parlophone sound engineering, even on a quick-fire single.

“I Feel Fine” was a standalone single, backed with the equally powerful “She’s a Woman.” While not formally on a UK album until later compilations, it was included on the US Capitol album Beatles ’65. Released in late 1964, it became a massive chart-topper on both sides of the Atlantic, their final Number One of that legendary year, a victory lap of sorts before the more contemplative, world-weary tone of the Beatles for Sale material fully took hold. It was a transitional track, looking back to the effervescent energy of A Hard Day’s Night while nodding forward to the studio experimentation that would define their later career.

If you listen to the song today on quality home audio equipment, the details are remarkable. The clarity of the mix reveals the distinct roles each Beatle plays: Ringo’s syncopated drumming, the riff’s insistent pulse, and the layered vocals. The simple, four-to-the-bar rhythm provided by a nearly inaudible, supplementary acoustic guitar is the secret ingredient that gives the main riff its relentless drive. The piece never falters, never loses its momentum. It’s a testament to the band’s innate, professional tightness, even when they were seemingly throwing the rules out the window.

The song’s impact ripples far beyond its chart success. That opening, distorted buzz—that feedback—cracked the door open for an entirely new sonic palette in popular music. It was a signal that the studio could be a laboratory, not just a documentarian. It gave permission to a generation of artists to embrace noise, distortion, and the “happy accident.” Imagine a young Jimi Hendrix listening to this single, hearing the controlled chaos. The entire landscape of rock and roll changed subtly with that one, audacious opening note.

My own connection to this track is a simple one, often heard late at night on classic radio. It’s the sound of effortless confidence—that moment when you’re young, in love, and the world just works. The simplicity of the lyrics (“I’m so glad she’s telling all the world…”) is the perfect foil to the complexity of the sonic invention. It’s the sound of a band that knew, without a doubt, they were at the top of their game and could get away with anything.

“The introduction of ‘I Feel Fine’ is a masterclass in accidental innovation, a brilliant piece of sonic vandalism that changed the trajectory of studio recording forever.”

The fact that the song is so structurally simple, built around a three-chord progression and a killer riff, only underscores its genius. There is no elaborate orchestral arrangement or sweeping piano break. It’s primal rock and roll, augmented by a technical glitch turned feature. Even the brief acoustic strumming of the rhythm guitar adds a layer of kinetic energy beneath the riff that you only appreciate after years of close listening. This is the difference between an old song and a timeless one: the capacity to still yield surprises, even decades later. It wasn’t just fine, it was revolutionary.

Listening Recommendations

- The Kinks – “You Really Got Me” (1964): Shares the raw, riff-driven, and slightly distorted rock foundation that defined the mid-60s sound.

- The Rolling Stones – “Satisfaction” (1965): Another perfect, instantly recognizable guitar riff used as the primary structural hook.

- The Beatles – “Ticket to Ride” (1965): A direct follow-up that shows The Beatles further integrating heavier, more complex drum patterns and darker tones.

- Bobby Parker – “Watch Your Step” (1961): The R&B track widely credited as the core inspiration for the main guitar riff.

- The Who – “My Generation” (1965): Demonstrates the increasing use of controlled noise, feedback, and aggression in the mid-sixties rock explosion.

- The Ventures – “Walk Don’t Run” (1960): Highlights the importance of the clean, instantly recognizable electric guitar riff in instrumental and early rock music.