It starts the way many lifelong loves begin: late-night radio, a single voice reaching across snow and static. “Sixteen Candles” doesn’t so much begin as materialize—Johnny Maestro’s tenor lit from within, the harmony stack moving in a gentle orbit, a drum pattern that suggests a slow dance more than it dictates one. You can hear the room in it, that small halo of reverb common to late-’50s New York recordings, the oxygen between the notes. The record feels handmade and evergreen all at once, the kind of thing you lean toward instinctively.

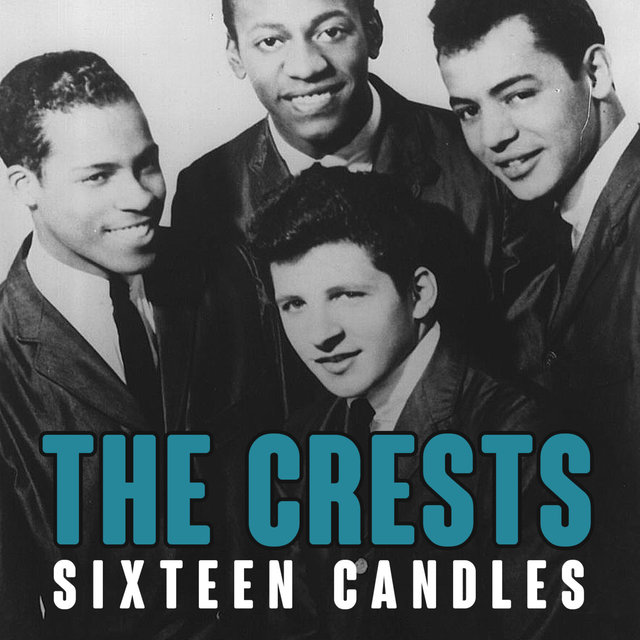

By the time The Crests cut “Sixteen Candles,” they were an anomaly that made perfect sense: an interracial New York vocal group built on equal parts street-corner blend and pop ambition, with Johnny Maestro—born John Mastrangelo—out front and J.T. Carter anchoring from below. Their breakthrough single arrived on Coed Records in October 1958, credited to writers Luther Dixon and Allyson R. Khent, and paired with the B-side “Beside You.” The song would peak at No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 in early 1959 and become a Top-5 R&B success, a national crush that refused to fade.

“Sixteen Candles” wasn’t just a hit; it was an introduction to the group’s sensibility—sincere, slightly formal, built for pop radio but drawn from the rich grain of doo-wop harmony. If you want the discographical bones: it was a stand-alone single first, later folded into The Crests’ 1960 long-player The Crests Sing All Biggies, a collection that framed their own smashes alongside reverent covers. That LP placement, even if secondary to the 45’s success, helped cement the track as a centerpiece of their identity.

The setting matters. Coed was a new label in 1958, co-founded by bandleader-publisher George Paxton and Marvin Cane, and it quickly made a mark cultivating East Coast vocal records with uncommon polish. Paxton reportedly produced many of Coed’s releases, and while individual session credits for “Sixteen Candles” can be murky in period sources, you can hear the label’s signature: a tidy mono picture, balanced backing parts, and a warm, radio-ready finish that lets the singer glow without drowning the group. Think Brill Building pragmatism married to street-corner romance—polish without plastic.

What does the record actually sound like when you listen closely, beyond nostalgia’s pleasant blur? It opens like a small stage being lit, one bulb at a time. The rhythm section keeps a gentle sway; the bass and brushed snare move like a heartbeat you’re holding back so you don’t step on your partner’s feet. A saxophone will surface briefly—more candle-flame flicker than neon sign—answering the vocal and shading the transitions. A softly chiming guitar places pinpoint accents that feel like the glint of paper streamers, and a modest keyboard figure—more bell-tone than flourish—settles the mood. Nothing is over-arranged; the arrangement trusts breath and space.

Maestro’s tenor is the linchpin. He sings as if he’s remembering the moment even while living it, with a tender vibrato that isn’t pasted on for effect but grows naturally out of the line. He leans into vowels, elongating them just long enough to make the harmony answer feel inevitable. There’s composure here—the restraint of a singer who knows that sincerity resonates more powerfully at a conversational volume. The other voices are placed like bows on gift boxes: not extravagant, but chosen with care.

And then there’s the emotional architecture. “Sixteen Candles” lives in the balance between sweetness and poise. On one side: a birthday scene, the innocence of a wish, the ritual of light. On the other: the understanding—never stated outright—that birthdays are markers of passing time. The performance acknowledges both without tipping into mawkishness. That may be why it still works in a world where metaphors of youth can feel threadbare: the record is honest about the ache that lingers after the cake is cut.

Here’s the part I return to whenever I put on the 45 or queue it up digitally: the record’s air. You can almost sense the distance between the lead and the mic, the way the harmony cluster sits slightly behind him in the soundstage. Mono doesn’t flatten the feeling; it focuses it. Play the track on decent speakers and you’ll hear a little shimmer on the high end, a soft cushion in the low mids. Through good studio headphones, the inner blend reveals itself—breaths, tiny consonants, the quick lock-in before a held note. That’s the miracle of craft: revealing everything while making the seams invisible.

The craft extends to the lyric’s framing device. Sixteen is a number, a milestone, a cultural token. But here it’s also a tempo: the group leans into a medium-slow pulse that lets the syllables hang just long enough to feel ceremonial. The chorus builds without climbing a mountain; there’s no power belting, no last-minute modulation to force catharsis. The drama is internal. You’re invited to remember your own room, your own lights, your own hands hovering above a cake for a breath longer than needed.

This design—quietly architectural, heavily human—helped the single become The Crests’ signature and their springboard to subsequent charting sides like “The Angels Listened In” and “Step by Step.” If Maestro later found fresh fame fronting The Brooklyn Bridge, it was because he had learned the value of articulate romance in compact form. “Sixteen Candles” taught him, and audiences, that you can command a stage by leaning in rather than leaning on. The Crests’ mixed-race lineup also mattered in the late-’50s pop landscape, a fact no less significant because it was handled without fanfare: the sound is the sound, and the sound is beautiful.

The record’s cultural afterlife is robust. It threaded through American Graffiti in 1973, became the title-song touchstone of John Hughes’s 1984 film, and has been covered in multiple styles—from the Stray Cats’ rockabilly gleam to soul and country readings—each version reaffirming how sturdy the melody is when translated into new clothes. That ubiquity is not merely nostalgia; it’s proof of a composition that invites fresh air without losing its core temperature.

Pull the camera back and the business story is instructive. Coed’s founders understood that doo-wop harmony could be presented as modern pop if you polished the edges and trusted a strong lead. Luther Dixon—who would go on to craft hits for the Shirelles—co-wrote this one with Allyson R. Khent, and the collaboration captured an idea larger than the market segment it serviced. The record feels built for everybody, and the charts of early 1959 bear that out. You can read the data, but you can also hear the universality in a single held note.

What keeps it fresh today? Partly the performance, partly the proportions. The band never crowds the singer. The dynamics slope upward like a graceful ramp rather than spike like a graph. Even the sax cameo is dignified, a small ribbon rather than a startled bird. Listen for the way the final refrain resolves without grandstanding—no ellipses, no exclamation marks. It ends the way a good wish ends: with a quiet breath and a gentle return to silence.

And if you want to feel it under a microscope, try a direct A/B listen: first on speakers in a lived-in room, then on a decent set of studio headphones. On speakers, the record is social—perfect for a kitchen where someone is icing cupcakes or a living room where a family friend tells an old story. In headphones, you discover the architecture of the blend, the hand-off between lead and backing, the way the sax peeks in as if to keep the candles from burning too low. It’s a reminder that fidelity and intimacy aren’t opposites; they are collaborators.

“Sixteen Candles” also carries well across listening contexts. The mono master is compact and forgiving, so it doesn’t crumble when compressed by radio, streaming, or vintage jukebox circuitry. For a song rooted in ritual, it has an unusually portable ritual of its own. You can drop it into a modern birthday playlist and it still sounds conversational rather than cute. You can use it as a palate cleanser between louder tracks, a reminder that love songs don’t always need to shout.

Let me tell you three micro-stories that keep this song alive for me:

A father in a split-level house on a winter weekend, turning 45s for guests as his daughter’s friends mill around the kitchen. He plays “Sixteen Candles” not as a wink but as a benediction, and for a moment even the teenagers stop to listen. The room feels older and younger at once.

A long highway at night, taillights stretching into red commas. The DJ segues out of a current pop hit into The Crests, and the car goes a little quieter. You don’t skip it. You turn it up a notch and let it write a soft edge around your evening.

A quiet apartment where someone is frosting a home-baked cake for themselves, because no one else thought to. They light two candles—one and six—and hold their breath while the chorus rises, making a wish that’s half memory, half promise. When the last note fades, the room doesn’t feel empty; it feels framed.

If you’re the type who discovers classics via a music streaming subscription, this track is a gentle teacher in how to hear arrangement choices: the staggered entries, the way the bass underpins without thumping, the modesty of the interlude. And if you’re a player, notice how little it takes to make it work. The chords are familiar; the trick is restraint.

There’s a reason this piece of music slides easily into new contexts without losing its identity. The language is simple, but the performance encodes respect—respect for the listener’s attention, for the singer’s breath, for the way harmony can console without explaining. It’s difficult to write about sincerity without tipping into sentimentality, but “Sixteen Candles” embodies sincerity as a discipline. The Crests don’t overwhelm the scene; they illuminate it.

Doo-wop often exists on the glamour-grit axis—street voices dressed in Sunday best. “Sixteen Candles” tilts toward polish, yet never forgets the sidewalk it came from. That’s where Coed’s aesthetic helps: they knew how to make records that felt instantaneous but also carefully framed, and this is one of their clearest demonstrations. The polish is a lens, not a glaze.

“ The promise in Maestro’s tenor is less about youth than about how memory refuses to grow old. ”

For those tracing The Crests’ arc, this single was the spark that threw light across the rest of their catalog. Subsequent hits kept the name in circulation, but “Sixteen Candles” is the calling card—an introduction so strong that later retrospectives routinely build their story around it. In reissues and compilations, it stands near the front door, greeting you with the offer of a dance.

If you want a physical anchor, the original Coed #506 pressing with “Beside You” on the flip remains a small treasure, and later collections make the track easy to find. The song’s presence in films and cover versions testifies to its malleability, but your own room is the test that matters. Play it there, softly. If you’ve never really listened, that first line will feel like a light being switched on inside your chest. If you already know every breath, it will feel like seeing an old friend across a crowded room.

Before we wrap, a brief note on lineage and context: Luther Dixon’s name connects The Crests to the broader trajectory of early-’60s Brill Building craft, and Allyson R. Khent’s co-writing credit is a reminder of the collaborative webs that sustained this era. Meanwhile, Coed’s small but impactful catalog—The Duprees, The Rivieras, and more—points to a label identity that valued classicism without calcifying it. “Sixteen Candles” sits at the center of these intersecting lines like a modest jewel.

What remains after all these years is the afterglow. I hear the song and think not of teenage rooms but of grown-up kitchens, long drives home, and quiet apartments lit by a laptop screen. The Crests found a way to write across time. If you want to study that lesson, put the track on and listen to how gently the arrangement ferries the voice. Then, if you must, compare it on different systems—your living-room speakers, your car, your most trusted studio headphones—and notice how it keeps its center no matter the frame.

One last craft observation. The record features a modest keyboard line—call it a music-box cousin of a piano—that functions like a steadying hand on the small of the song’s back. It’s barely there, yet you’d miss it if it were gone. That’s how “Sixteen Candles” is built: with elements so right-sized you don’t notice the engineering until you look for it. And that, more than any cultural footnote, may be the reason it endures.

In a world obsessed with volume and velocity, this is a reminder that the heart sometimes moves at a slow dance. Light the candles, take the breath, lean in. Some wishes don’t have to be shouted to be heard.

—

Listening Recommendations

The Penguins — “Earth Angel (Will You Be Mine)”

Doo-wop devotion in slow motion; a similarly tender sway built on close harmonies and patient phrasing.

The Skyliners — “Since I Don’t Have You”

An elegant late-’50s ballad where strings and voice trace the same delicate arc toward yearning release.

Dion and the Belmonts — “A Teenager in Love”

Breezier tempo and brighter vowels, but the same knack for turning adolescent ritual into adult-sized melody.

The Crests — “The Angels Listened In”

From the same hitmaking stretch; a harmonic lift that shows how the group could sparkle without rushing.

The Five Satins — “In the Still of the Night”

A chapel-warm classic whose atmosphere and pacing echo the quiet ceremony that makes “Sixteen Candles” glow.

Jackie Wilson — “Lonely Teardrops”

A different energy—uptempo R&B—but it shares the era’s emphasis on immaculate leads and emotionally direct hooks.