The lights were out, the tape spooling fast in a California studio late in 1966. On the tape, a nascent band named The Electric Prunes was trying to capture the sound of a nightmare turning into a scream. What they captured was a musical Big Bang, a three-minute explosion of reverb and reverse effects that would, almost instantly, define a new subgenre of rock music. “I Had Too Much to Dream (Last Night)” is not just a great record; it is a vital hinge-point in cultural history, the moment the teenage garage band grew up, got weird, and plugged into a fuzz box the size of a suitcase.

Let’s be clear about the context: the song was not recorded by Freddie Garrity or his band The Dreamers, whose comedy-tinged Merseybeat career was already winding down by 1967. Garrity, the famously energetic, bespectacled frontman, specialized in light-hearted British Invasion hits like “I’m Telling You Now.” The song under review is the signature work of the Los Angeles band, The Electric Prunes, a much grittier, heavier, and more experimental outfit whose debut single became an unexpected global hit.

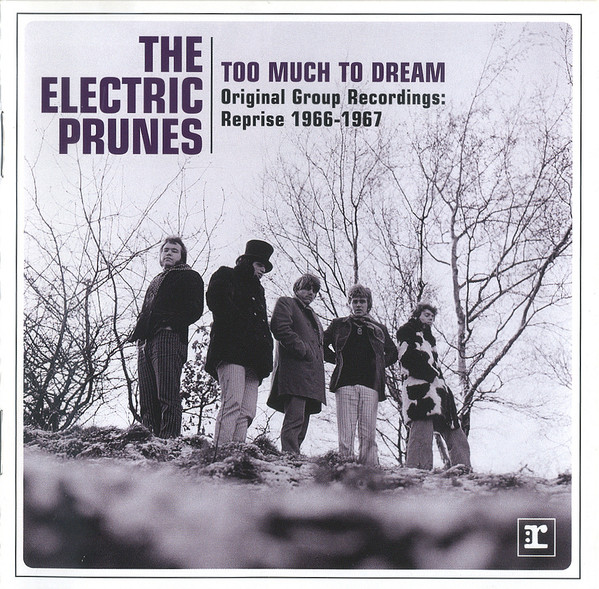

The track, released late in 1966 and peaking on the charts in early 1967, was the cornerstone of their self-titled debut album. It was produced by the legendary engineer Dave Hassinger—known for his work with The Rolling Stones—at a time when American rock was transitioning from simple beat music to something far more complex and chemically informed. This single was the essential signpost marking the way.

The Startle: Unpacking the Sonic Assault

The opening alone is a masterclass in controlled chaos, a hook that grabs the listener by the eardrums. It begins with a muted, oscillating feedback sound that is quickly revealed to be a backward-running guitar tape loop—a shock of sonic disorientation. It’s followed by a violent, wet-sounding cymbal crash and then a guitar figure that stings like a thousand needles. This wasn’t merely rock; it was anti-rock, actively distorting the expected sound.

The genesis of this sound is a fantastic piece of studio lore. Guitarist Ken Williams had been experimenting with his Bigsby vibrato and heavy fuzz. Reportedly, during a break in recording at Leon Russell’s home studio, the engineer played back a tape reel backwards, inadvertently capturing the decay of the guitar being manipulated at the tape’s tail end. The resulting piece of music was an immediate sonic blueprint for the psychedelic sound.

The moment the main rhythm section drops in, the contrast is arresting. Drummer Preston Ritter and bassist Mark Tulin establish a driving, aggressive pulse—a simple, muscular garage beat that pushes against the surrounding cosmic strangeness. This push-pull dynamic is key: the primal rock rhythm section keeps the song grounded, while the effects-laden guitar work and vocals pull it toward the abyss.

The Voice in the Void

Vocalist James Lowe delivers the lyrics with a brilliant sense of detached dread. He’s not singing about dreams of love or glory; he’s singing about a post-dream hangover, a waking anxiety about a former lover. His voice is deep, almost monotone, hushed against the musical storm until the chorus, where he unleashes a slightly flat, strangled shout: “I’ve got a feeling, a feeling deep inside!”

The dynamic is masterful. The verse is tight, minimal, carried by Mark Tulin’s simple but grounding bass line and a faint, distant organ or piano texture (also played by Tulin) that adds a ghostly presence. But the explosion in the chorus is all-consuming, with Ken Williams’s fuzzed-out guitar screaming and diving. It’s an aural representation of the singer’s internal world fracturing.

This tension—the whisper and the scream—demands a level of fidelity rarely expected from garage rock. Listening to this track today on a good pair of studio headphones reveals the intricate layering of the distortion and the deep, rich quality of the reverb tails. It’s a dense, textured production that moves far beyond the tinny immediacy of earlier garage recordings. Producer Dave Hassinger, who had engineered classics for the Stones, brought a world-class studio ear to the Prunes’ raw energy.

The Waking Nightmare: Context and Legacy

“I Had Too Much to Dream (Last Night)” was written by the professional songwriting team of Annette Tucker and Nancie Mantz, a fascinating detail given the track’s wild, anti-commercial sound. Reportedly, they conceived the song as a simple, orchestral piano ballad. The Electric Prunes and Hassinger violently re-imagined it, proving that the execution—the sonic dressing—was everything in 1967. The Prunes, like many garage bands, struggled with the fact that much of their debut album was dictated by outside writers and the producer, but this track remains their untouchable testament.

The song’s success, peaking at number 11 on the Billboard Hot 100 and charting in the UK, signaled that the mainstream was ready for something genuinely strange. It became the unwitting centerpiece of the burgeoning psychedelic rock movement and was famously chosen to open Lenny Kaye’s seminal 1972 compilation, Nuggets: Original Artyfacts from the First Psychedelic Era. That placement cemented its place as the definitive opening statement for the entire garage-psychedelic sound.

“The greatest psychedelic rock is not about floating away; it’s about the terrifying realization that your feet are still on the floor while your mind is airborne.”

For a generation, this single was the gateway drug into darker, more experimental music. It’s a song about the disorientation of waking life, the lingering fear that what you saw behind closed eyes might be more real than the morning sun. It captures a universal moment of existential dread, filtered through a terrifyingly innovative sound. This piece of music remains shockingly fresh, a visceral, thrilling three-minute acid trip that is absolutely required listening. It is the sound of the ’60s consciousness expanding, not gently, but with a sudden, violent jolt.

Listening Recommendations: Echoes in the Void

- The Seeds – “Pushin’ Too Hard” (1966): Shares the driving, aggressive garage-rock backbone and raw, sneering vocal delivery.

- 13th Floor Elevators – “You’re Gonna Miss Me” (1966): Features a similar, frantic psychedelic energy and a memorable, screaming vocal performance.

- The Blues Magoos – “We Ain’t Got Nothin’ Yet” (1966): Uses prominent organ and fuzz-guitar effects to create a heady, hypnotic groove adjacent to the Prunes’ sound.

- Ultimate Spinach – “Mind Flowers” (1968): Represents the later, more extended, and overtly acid-influenced tracks that followed the Prunes’ successful blueprint.

- Strawberry Alarm Clock – “Incense and Peppermints” (1967): A lighter, more playful side of psychedelic pop that shares the use of effects and complex vocal textures.

- The Amboy Dukes – “Journey to the Center of the Mind” (1968): Captures the same mixture of heavy, distorted guitar rock and explicit psychedelic thematic content.