When Hollywood and the Honky-Tonk Met Under a Darkened Sky

There are Western songs that tell stories. And then there are Western songs that become stories—living, breathing extensions of the frontier myth. “The Hanging Tree,” recorded by Marty Robbins in 1959, belongs firmly in the latter category.

Unlike many of Robbins’ self-written gunfighter epics, this haunting ballad was born from the silver screen. It served as the powerful theme to the 1959 Western film of the same name, starring Gary Cooper. From the very first notes played over the opening credits, the song establishes a mood of foreboding, regret, and destiny—casting a long shadow before a single line of dialogue is spoken.

More than just a soundtrack companion, “The Hanging Tree” became a cultural touchstone, bridging country music and Hollywood grandeur at a time when Westerns ruled both radio waves and box offices.

A Chart-Climbing Western With Oscar Pedigree

Released as a single in 1959, the song demonstrated Robbins’ remarkable crossover appeal. It reached No. 15 on the U.S. Hot C&W Sides chart and crossed over to peak at No. 38 on the Billboard Hot 100—an impressive feat that underscored how Western storytelling could captivate mainstream audiences.

Even more remarkable, the song was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Song in 1960. That distinction alone speaks volumes. Western theme songs were popular—but Oscar recognition elevated “The Hanging Tree” into rarefied territory.

Behind its powerful composition stood Hollywood heavyweights. The music was scored by legendary composer Max Steiner, the same visionary who crafted the film’s orchestral backbone. The lyrics were written by the accomplished duo Mack David and Jerry Livingston, whose words distilled the film’s sweeping drama into poetic metaphor.

Together, they created something more than a promotional song. They created a Western morality tale wrapped in melody.

The Tree as Symbol: Death, Memory, and Lost Dreams

At first glance, the “hanging tree” is a grim and literal image—an execution site in a rough gold rush town. But the genius of the song lies in its layered symbolism.

The story follows a man who arrives in a frontier settlement chasing fortune, yet burdened by the ashes of a lost love. Before he even begins his quest for gold, he performs a symbolic act: he leaves his heart—his memories, his hope—“hanging” on the tree. It is emotional self-execution. He chooses numbness over vulnerability.

Then comes the twist of fate so common in Western mythology. He finds gold. He finds a woman who loves him. By all measures, he has achieved success.

But he cannot return her love.

Why? Because emotionally, he never reclaimed his heart. It still hangs from the branch where he left it.

The tree becomes more than a place of death—it becomes a repository of regret.

The Climactic Reckoning

As with all powerful ballads, destiny arrives swiftly and without mercy. The protagonist’s gold draws envy and danger. Violence erupts. He is dragged—ironically—to the very tree where he symbolically abandoned his heart.

Here, metaphor collides with reality.

Facing literal death beneath the same branches that once held his dreams, he experiences a moment of awakening. In a dramatic turn worthy of classic cinema, love intervenes. Salvation arrives—not just physical rescue, but emotional rebirth.

The hanging tree transforms from a gallows into a gateway.

This transformation is the song’s emotional core. It suggests that redemption often requires confrontation. We must return to the place where we buried our pain. We must stand beneath the tree again.

Only then can we walk away truly alive.

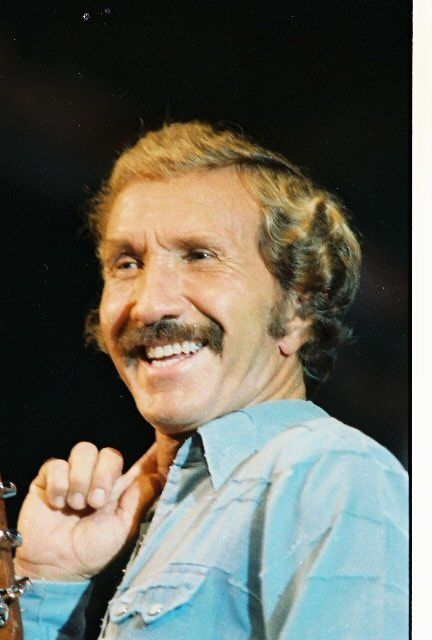

Marty Robbins’ Cinematic Delivery

Marty Robbins possessed one of the most distinctive voices in country music—clear, controlled, yet capable of immense dramatic weight. In “The Hanging Tree,” he doesn’t simply sing; he narrates with a steady gravity that feels carved from canyon stone.

There is restraint in his phrasing, a calmness that mirrors the stoic Western hero archetype. Yet beneath that composure lies quiet intensity. He allows the orchestration—rich with sweeping strings courtesy of Max Steiner—to swell around him like desert wind before a storm.

The result is cinematic country at its finest.

Robbins’ performance was so definitive that the Western Writers of America later recognized the song among the Top 100 Western Songs of All Time—a testament not only to its storytelling power but to the authenticity Robbins brought to every note.

A Tree of Death Becomes a Tree of Life

For older listeners especially, “The Hanging Tree” resonates as more than a Western tale. It becomes a meditation on aging, regret, and emotional courage.

How many of us have left parts of ourselves “hanging” somewhere in the past?

A heartbreak we never resolved.

A dream we buried.

A risk we were too afraid to take again.

The song suggests that we cannot outrun those abandoned pieces. Prosperity means little without emotional wholeness. Gold without love is empty weight.

Yet it also offers hope. The tree that once symbolized execution becomes, through confrontation and love, a Tree of Life. Redemption is possible—but only if we return to claim what we left behind.

Why “The Hanging Tree” Endures

In today’s fast-moving musical landscape, few songs carry this level of narrative depth. “The Hanging Tree” stands as a reminder of a time when mainstream hits could tell complex stories in under three minutes.

It bridges worlds:

-

Hollywood and Nashville

-

Cinema and radio

-

Romance and mortality

It also captures the enduring Western paradox: harsh landscapes giving birth to profound tenderness.

While Marty Robbins is often remembered for his gunfighter ballads, this song reveals another dimension of his artistry. Here, the bullets are metaphorical. The showdown is internal. The victory is emotional.

And perhaps that is why it continues to linger in the American imagination.

Final Reflection

“The Hanging Tree” is not merely about frontier justice or gold rush greed. It is about the universal human journey toward healing. It reminds us that sometimes we must stand again beneath the very branches where we once felt broken.

Only then can we walk away free.

Under Marty Robbins’ steady voice, the gallows become a symbol not of ending—but of beginning.

And that is the quiet miracle at the heart of this unforgettable Western ballad.