The first time I really heard “Hey Joe,” I was sixteen, hunched over a pair of borrowed, mid-range studio headphones late on a Saturday night. It wasn’t a casual stream; it was a physical moment, the kind of concentrated listening that feels like an intrusion into a private ritual. The recording, a single from late 1966 that launched a thousand ships (and the UK career of The Jimi Hendrix Experience), was more than just music; it was a manifesto wrapped in a blues-rock murder ballad.

This piece of music arrived in the British winter of 1966, an anomaly of heat and texture amongst the polite pop landscape. It was released by Polydor before the Experience had firmly settled with Track Records, a strategic move by manager and producer Chas Chandler. Chandler, the former Animals bassist, had found Hendrix in a small New York club and recognized the impending musical earthquake. He brought the young American to London with a clear vision: launch him with a compelling cover of the well-traveled folk song, “Hey Joe.”

The track would later be added to the American release of their debut album, Are You Experienced, an inclusion that retroactively frames the song as a foundational statement, though it stood alone as a single initially, climbing to a respectable peak on the UK charts in early 1967. The strategy worked: this was the first time most of the world was exposed to the man who would redefine the electric guitar.

The Architecture of Dread

The opening is cinematic in its simplicity, yet instantly establishes the tension that will define the narrative. There is no flamboyant solo to kick off the proceedings; instead, the song begins with Noel Redding’s descending bass line, a slow, deliberate walk down the circle of fifths (C-G-D-A-E) that lends an undeniable sense of fateful movement. Mitch Mitchell’s drums enter with a restrained, yet precise, swagger—all press rolls, tight snare work, and subtle cymbal accents that propel the doom-laden groove without ever becoming frantic.

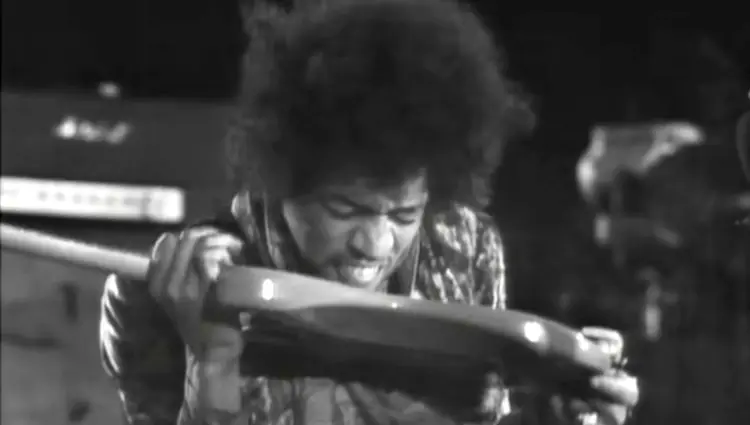

Hendrix’s guitar enters the fray, not with a blast of feedback, but with a shimmering, almost bell-like arpeggiated figure. It is clean, but thick with a strange, aqueous reverb and just enough vibrato to suggest a nervousness beneath the surface. This is the sound of a man standing at a crossroad, a loaded weapon in his hand. The arrangement is stark: bass, drums, and one electric guitar providing rhythm, melody, and atmosphere simultaneously, a testament to the “power trio” model they were perfecting.

Crucially, there is no piano on this track. Its absence focuses the listener entirely on the dynamic interplay of the three instruments, leaving a vast, dark space for the drama to unfold. Had a piano been involved, its harmonic richness might have softened the edges, diluted the grit. Chandler and Hendrix understood that the story—the chilling tale of a man fleeing to Mexico after shooting his cheating woman—needed a stark, unforgiving soundscape.

Voice and Verve: The Unspoken Threat

Hendrix’s vocal delivery here is surprisingly gentle, almost resigned. He doesn’t yell the lyrics; he narrates them with a calm, almost casual menace. “Hey Joe, where you goin’ with that gun in your hand?” the backing vocalists—reportedly the female group The Breakaways—ask in a higher register, providing an echo of societal judgment or perhaps Joe’s own conscience. This contrast between the smooth, almost conversational lead vocal and the haunting, almost choir-like response is a masterstroke of arrangement.

But the true genius, the signature that scorched this version onto the annals of rock history, is the playing between the vocal lines. Each time Joe pauses, the guitar answers, a short, sharp interjection, a flash of lightning. These aren’t just fills; they are narrative commentary, little micro-bursts of sound that say more than the words themselves. The tone is already fully formed: slightly compressed, harmonically rich, utilizing a wah-pedal perhaps more subtly than he would later, giving the notes a vocal, crying quality. He bends the strings, stretches the notes, and lets the low E string drone with a sustained intensity that had simply not been heard before.

“The Experience’s ‘Hey Joe’ is not just a recording; it’s the sonic fingerprint of a legend taking his first public breath.”

I remember playing this song for a college friend, a classically trained musician who usually dismissed rock. She leaned in, focusing on the way Hendrix would slide into a chord, the almost human quality of his vibrato. “It’s like he’s playing the blues,” she noted, “but he’s turning the notes inside out.” And that’s precisely it. Hendrix didn’t just play the notes; he manipulated the sound waves, exploiting the very limits of amplification and effects to create a tangible, tactile texture.

The Legacy Beyond the Chord Progression

Many artists before and after covered “Hey Joe,” from the folk roots of the song’s probable originator, Billy Roberts, to the garage rock rush of The Leaves. But Hendrix’s version transcends the simple chord progression (which famously moves in descending fifths). It transforms a traditional blues story into an acid-rock blueprint.

For the aspiring musician, “Hey Joe” is a rite of passage. Not because the chord changes are complex—they are not—but because mastering the feel is nearly impossible. Many an enthusiast buys guitar lessons hoping to decode the secret of that effortless groove, only to realize the real magic lies not in the tabs, but in the micro-timing, the attack, and the subtle dynamic shifts between Mitchell’s light touch and Redding’s robust foundation. The simplicity of the core structure is the perfect canvas for Hendrix’s innovative, almost improvisational phrasing.

The recording quality, steered by Chas Chandler and engineers like Dave Siddle, captures the raw, immediate energy of a nascent band. It is a four-track recording, but the judicious use of effects—the swirl of the wah, the depth of the reverb—makes it sound massive, far bigger than its modest studio origins. The track’s lasting power is that it remains visceral, a document of a moment when the future of rock and roll was being forged in a London studio. It is heavy without being metal, psychedelic without losing its blues moorings. It’s an essential bridge between the Chicago blues masters and the guitar gods of the 70s. Re-listening today, the recording remains shockingly immediate, a perfect snapshot of a genius on the cusp of conquering the world.

Listening Recommendations

- Tim Rose – “Hey Joe” (1966): The slower, dramatic arrangement Rose popularized was the direct inspiration for Hendrix’s version.

- The Leaves – “Hey Joe” (1966): A contrasting, fast-paced garage-rock take that shows the song’s adaptability across genres.

- Cream – “I Feel Free” (1966): Early power-trio track with a similarly tight rhythm section and soaring, blues-infused guitar work.

- Jeff Beck Group – “Morning Dew” (1968): Another dark, folk-influenced cover re-imagined by a British guitar hero with a flair for dramatic, blues-rock arrangements.

- Love – “My Flash on You” (1966): Shares a similar blend of emerging psychedelic texture with a raw, rock-band drive from the same era.