The air in Olympic Studios must have felt electric. You can almost imagine it: the low hum of vacuum tubes in the Marshall amps, the scent of hot metal and ozone, the quiet tension as the four-track tape machine spooled up. It was late 1966 or early 1967, and a trio of relative unknowns was about to open a fissure in the fabric of popular music, a fault line from which the future would pour out.

That future began with two notes. A G and a D-sharp. The tritone. An interval so dissonant and unsettling that for centuries it was dubbed diabolus in musica—the devil in music. It was the sound of a question mark, a challenge hurled into the polite, post-Merseybeat world. This was the opening salvo of “Purple Haze,” and for anyone hearing it for the first time, it was less an introduction and more a rewiring of the senses.

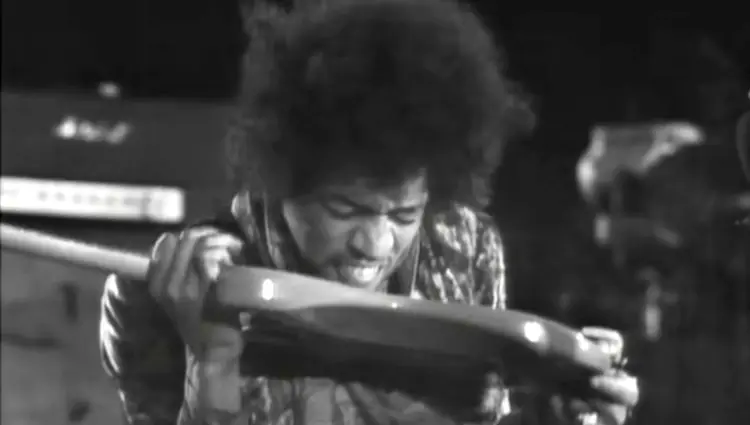

Released as a single in the UK in March 1967, “Purple Haze” was only the second release from The Jimi Hendrix Experience. It followed the success of their smoldering cover of “Hey Joe,” but where that song introduced a prodigious talent, this one unleashed a cosmic force. Under the guidance of producer and former Animals bassist Chas Chandler, Hendrix was encouraged to write his own material, to let the strange and beautiful sounds in his head take flight. The track would later become the electrifying opener for the US version of their debut album, Are You Experienced.

The sound itself felt alien. The guitar at the center of it wasn’t just strummed or picked; it was wrangled, tormented, and coaxed into speaking a new language. The riff, doubled an octave higher with the help of a prototype Octavia pedal, sizzles with a fuzz-drenched texture that feels both abrasive and intoxicating. It’s a sound that seems to tear a hole in the speaker cone, a raw, untamed energy that had simply never been captured on tape before.

Then comes the lyric, a masterpiece of psychedelic ambiguity. “Purple haze all in my brain / Lately things just don’t seem the same.” Hendrix claimed the line came to him in a dream after reading a science fiction novel, a vision of walking under the sea. But listeners heard what they wanted to hear: a shorthand for the lysergic confusion of the counterculture, an anthem for altered states. The verses tumble out in a stream of consciousness, a disjointed narrative of lost time and scrambled senses. Is he talking to a girl? To himself? To God? The power is that it could be any, or all, of them.

But to focus solely on Hendrix is to miss the explosive chemistry of the Experience. On drums, Mitch Mitchell is not a timekeeper; he is a co-conspirator. His fills are not just rhythmic flourishes but frantic, jazz-inflected conversations with the guitar. He responds to Hendrix’s every move with a tumbling, cymbal-splashed chaos that propels the track forward with breathtaking volatility. He is the storm surge crashing against the cliffs of Noel Redding’s bassline. Redding is the anchor, his simple, driving part the bedrock upon which the entire psychedelic cathedral is built.

Then there is the solo. It arrives not as a melodic break but as a detonation. It’s a torrent of blues licks fed through a filter of pure sonic experimentation. The notes bend and scream, dive-bombing into oblivion before roaring back to life. This was a statement. It declared that the guitar was not merely a tool for crafting pleasant melodies but an instrument capable of expressing the full spectrum of human chaos and ecstasy. No amount of conventional guitar lessons could ever prepare a player for this kind of revolutionary thinking; it was a leap of imagination.

“It was a sound that seemed to tear a hole in the speaker cone, a raw, untamed energy that had simply never been captured on tape before.”

Even the song’s structure is subversive. It dispenses with a traditional chorus, instead returning again and again to that monstrous, unforgettable riff. The piece of music ends in a cacophony of distorted, sped-up guitar noises, amplifier feedback, and indistinct chatter, fading out not with a sense of resolution but with the feeling of a machine breaking down or a signal being lost to the static of deep space. It’s an unsettling, brilliant conclusion that refuses to offer easy answers.

Imagine a teenager in 1967, huddling close to a transistor radio, waiting for the DJ to spin the latest hits. Amidst the polished pop and soulful ballads, this song erupts. It would have sounded like a broadcast from another planet. The distortion, the feedback, the sheer volume of it all—it was a seismic shock, a declaration that the rules had changed overnight. The clean, orderly progression of pop music was over.

Even today, hearing this track on a pair of high-quality studio headphones reveals its raw power and intricate texture. You can hear the hum of the amps, the scrape of the pick on the strings, the way Mitchell’s cymbals shimmer and decay in the room. It remains a visceral experience, a reminder of a time when rock music felt genuinely dangerous and boundary-breaking. The song’s structure defied the neat, chordal logic of a standard pop song, which often found its home on the piano. Hendrix was building with different materials altogether.

“Purple Haze” is more than just a classic rock staple. It is a moment of becoming. It’s the sound of Jimi Hendrix discovering the full, terrifying extent of his own power and, in doing so, showing generations of musicians a new path forward. It’s a snapshot of a cultural moment, yes, but its ferocity and invention feel timeless. This wasn’t just a new track for a debut album; it was Year Zero for the electric guitar.

Go back and listen to it now. Don’t just hear it as a song you know. Hear it as the sound of a door being kicked off its hinges, revealing a vivid, electrifying, and slightly terrifying new world on the other side.

Listening Recommendations

- Cream – “Sunshine of Your Love”: For its similarly iconic, heavy, and blues-derived central guitar riff that defined an era.

- The Troggs – “Wild Thing”: Captures a similar raw, proto-punk energy with a guitar sound that leans into glorious, distorted simplicity.

- Jeff Beck Group – “Beck’s Bolero”: An instrumental masterpiece from the same period showcasing another guitar innovator pushing the limits of studio technology and composition.

- The Seeds – “Pushin’ Too Hard”: Shares that snarling, defiant garage-rock attitude and a sense of barely-contained chaotic energy.

- Funkadelic – “Maggot Brain”: A later, epic evolution of psychedelic guitar-as-personal-exorcism, taking Hendrix’s emotional fire into the cosmos.

- Blue Cheer – “Summertime Blues”: For its groundbreaking heavy, sludgy, and overdriven sound that took the power of the Hendrix trio to a deafening extreme.