There are records that encapsulate a moment, and then there are records that feel like the moment’s final, gorgeous exhalation. The Love Affair’s 1969 single, “Bringing On Back The Good Times,” belongs firmly to the latter category. It is a piece of music of exquisite contradiction—euphoric in its arrangement, yet profoundly melancholic in its placement on the timeline of British pop. Released just months before the decade bled into the 1970s, it serves as a shimmering, ambitious farewell to an era of high-drama, orchestrated pop, an era The Love Affair had dominated, however fleetingly.

The band’s career arc had been a classic lightning strike of overnight success followed by the friction of maintaining altitude. They hit the absolute peak of the UK charts in 1968 with the colossal “Everlasting Love,” a track that defined the genre with its powerful vocal and rich, session-musician-driven orchestration. But this success came with an asterisk that haunted them: the label’s reliance on professional session players rather than the band members themselves for the backing tracks, a practice that rankled the group’s core and created a persistent, undermining narrative of inauthenticity.

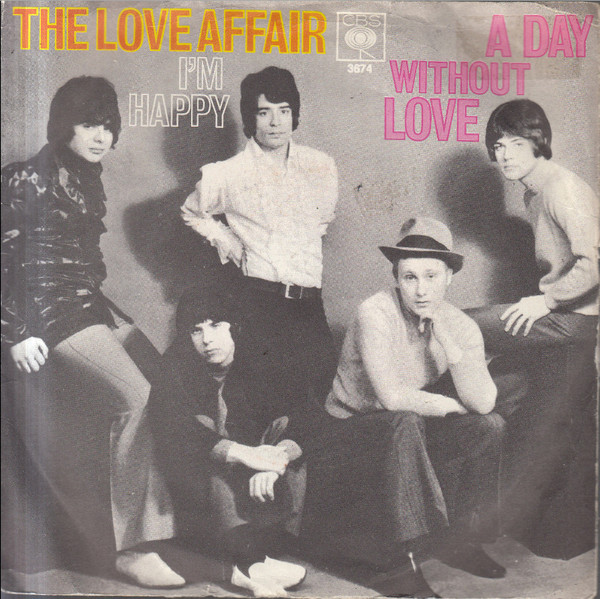

By 1969, The Love Affair, fronted by the phenomenal soul voice of Steve Ellis, had built a respectable run of UK Top 20 hits on the CBS label, including “A Day Without Love” and “Rainbow Valley.” “Bringing On Back The Good Times,” composed by Phillip Goodhand-Tait and John Cokell, arrived in July of that year, charting well in the UK and in other territories, extending their reign for one final, glorious summer. It was not attached to a contemporary album, released instead as a stand-alone 45, the central commodity of the time. The single was produced by the veteran Mike Smith, who had overseen their entire hit run, with the sweeping, cinematic arrangements reliably credited to the talented Alan Hawkshaw.

The moment the needle drops, the air is thick with anticipation. It opens not with a raw guitar riff, but with a majestic, swirling string section that immediately signals the track’s grand intent. This is the sound of late 60s British pop ambition, taking a page from Motown’s playbook and then coating it in a lush, London studio sheen. The string arrangement is not merely accompaniment; it is a vital, dynamic character in the song’s story, soaring during the choruses and providing counter-melodies during the verses, executed with a precision that defines the premium audio standard of the era.

The main rhythm section—which, following the trend set by “Everlasting Love,” reportedly featured top session men—is tight and propulsive. The drums, likely played by a studio stalwart such as Clem Cattini, have a crisp, almost militaristic roll that drives the mid-tempo feel. The bassline is muscular and melodically active, anchoring the whole magnificent structure. This rhythmic solidity is the engine room, providing the contrast against which the lightness of the vocal and the orchestration can truly fly.

And then there is Steve Ellis. His voice, with its raspy, soulful edge, cuts through the rich instrumental tapestry with breathtaking clarity. He possessed a maturity far beyond his years, channeling the passion of American soul singers like Steve Marriott and Stevie Winwood but delivering it with an unmistakable British pop sensibility. His phrasing on the title line, “Bringing on back the good times,” is a masterclass in controlled catharsis—not shouting, but passionately declaring the shift from sadness to joy.

The instrumentation creates a complex, appealing texture. There’s a distinctive, bright piano part that plays a simple, memorable motif, often heard dancing in the upper register, providing a light, almost music-hall-inflected contrast to the heavy strings. While there might be an overdubbed acoustic guitar strumming in the background for rhythmic texture, this is not a record built on rock foundations; it is a creation of the arranger’s pen, a highly-engineered pop sculpture.

The song is a brilliant example of the “Wall of Sound” technique adapted for the swinging London scene. It’s multi-layered without ever sounding cluttered. Listen closely on good studio headphones to the way the layered backing vocals—sweet, perfectly pitched female voices—enter just before the chorus. They act as a heavenly choir, lifting Ellis’s lead vocal and pushing the emotional payload into the stratosphere. This sophisticated use of vocal arrangement adds another dimension of glamour, making the central message of romantic renewal feel absolutely monumental.

The track’s initial success in the charts—a decent run, settling into the UK Top 10 range—was unfortunately a final peak rather than a springboard. By the end of 1969, the musical landscape was shifting dramatically. The lush, polished, highly-produced sounds of orchestral pop were being swept away by the gritty authenticity of hard rock, the conceptual depth of progressive rock, and the rootsy sincerity of the singer-songwriter movement. The backlash against the use of session musicians grew louder, and the pop machine that had built The Love Affair began to spin into irrelevance.

Ellis, feeling the artistic compromise and the commercial pressure keenly, departed the band in December 1969. The group, effectively, ended right there, leaving “Bringing On Back The Good Times” as an artifact—a perfect, polished diamond from a soon-to-be-closed mine. It is a song that sounds like hope, yet it soundtracks a breakup, both personal (the lyrical theme of a returning lover) and professional (the band’s imminent split).

“It’s not just a song about a return to happiness; it’s an aural monument to a particular kind of beautiful, doomed pop spectacle.”

Today, the track demands to be appreciated not as a relic, but as a masterpiece of craft. It’s a reminder of a time when pop singles were treated with the weight and gravity of a major film score, where every flourish of the flute and every swell of the violins was precisely placed for maximum emotional impact. Forget the history for a moment and simply surrender to the richness of the sound. The sheer effort and expense poured into this three-minute triumph is audible, undeniable, and truly inspiring. It’s a piece that invites listeners to not just remember the good times, but to actively bring them back, one gorgeous string crescendo at a time.

Listening Recommendations: Adjacent Sounds

- The Herd – “I Don’t Want Our Loving to Die” (1968): Shares the same grand-scale, orchestrated British pop ambition and youthful soul vocal.

- Amen Corner – “(If Paradise Is) Half As Nice” (1969): Another example of a UK soul-pop group embracing massive orchestral arrangements for a chart-topping result.

- The Foundations – “Build Me Up Buttercup” (1968): Features a similarly energetic, soul-influenced vocal delivery over a bright, brass-and-string-heavy arrangement.

- Marmalade – “Reflections of My Life” (1969): A slightly more psychedelic take on orchestrated pop, but with the same emphasis on a sweeping, romantic soundscape.

- Jimmy Ruffin – “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted” (1966): The American Motown soul that influenced the depth of the production and the powerful, earnest vocal delivery.

- The Cascades – “Rhythm of the Rain” (1962): For the delicate, yet soaring string and vocal texture that presaged this kind of emotional pop drama.