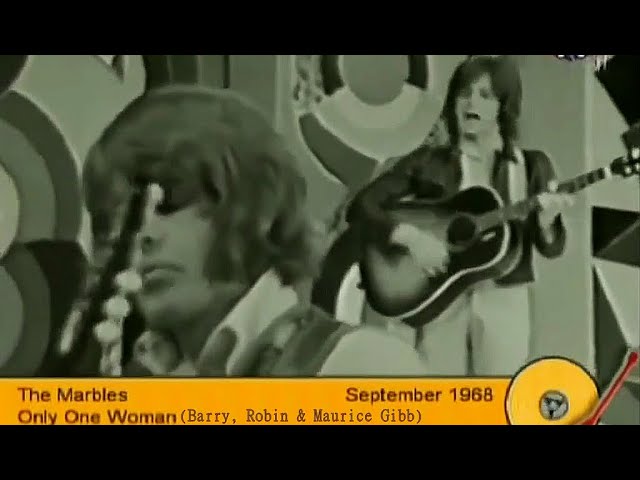

The air in the café was thick and humid, the kind of late summer evening where the city seemed to hold its breath. I was nursing a lukewarm filter coffee, pretending to read, when it started—that unmistakable, melancholy chime. It wasn’t a new sound, not even a contemporary one, but a perfect echo from the twilight of 1968. The moment that single, solitary piano chord hung in the air, everything in the room receded. It was The Marbles’ “Only One Woman,” a song that still carries the dramatic sweep of its era like a heavy velvet cloak.

The Marbles were, for many, a flash of comet light: a duo consisting of cousins Graham Bonnet and Trevor Gordon, whose career arc was as brief as it was brilliant. This magnificent song, their debut single, was their defining moment, a classic of what would become known as orchestrated pop. It was released by Polydor in the UK and Cotillion in the US, finding its greatest success in Europe. The track was their breakthrough, reaching the UK Top 5 and climbing even higher in other territories like the Netherlands and South Africa. This was, in essence, their career.

The story behind this piece of music is almost as compelling as the sound itself, a crucial detail in the intricate web of late-60s British music. The track wasn’t homegrown; it was a gift, a powerhouse composition from the masters of symphonic pop, the Brothers Gibb: Barry, Robin, and Maurice. It’s impossible to discuss The Marbles’ short, sharp legacy without acknowledging the benevolent shadow of the Bee Gees. The Gibbs, fresh from their own international success, not only penned this song but also helped secure the duo’s contract with impresario Robert Stigwood. In a marvelous act of support, Barry and Maurice Gibb even contributed to the backing track, alongside the Bee Gees’ drummer, Colin Petersen.

The arrangement, overseen by the masterful Bill Shepherd, is the song’s central character. It’s not subtle, nor should it be. From the opening, we are plunged into a world of high drama. That initial, sustained piano chord gives way to a rapid, urgent pulse from the rhythm section. The drums, reportedly featuring Colin Petersen, have a clipped, almost military precision, a subtle tension that pulls against the soaring melody. The texture is immediately rich: the bassline is present and warm, weaving through the lower registers with purpose.

Then the strings enter, a luxuriant wash that fills every corner of the sonic landscape. Shepherd’s orchestral arrangement elevates the song far beyond a mere pop tune; it transforms it into a three-minute, high-stakes opera. The strings are not a mere backdrop; they perform call and response with the vocal, swelling dramatically on the word “woman” in the chorus. This heavy, cinematic instrumentation is pure late-sixties pop grandeur. The song exists primarily as a mono mix, which only concentrates the intensity, pushing all that glorious sound directly at the listener.

The true lightning rod, however, is Graham Bonnet’s voice. The vocal performance here is a revelation, a raw, almost operatic display of power and control. Bonnet, who would later be known for his hard rock and heavy metal turns in bands like Rainbow and Alcatrazz, deploys his formidable instrument with a stunning, youthful emotionality. He is desperately pleading, his vibrato taut with conviction. The line “You can search the whole world over / But you won’t find another” is delivered not as a romantic cliché, but as a statement of devastating, final truth.

The instrumentation gives Bonnet the perfect stage. A soft, clean guitar line—reportedly played by Barry Gibb—offers a gentle counter-melody in the verses, a moment of vulnerability before the orchestra’s mighty return. This delicate acoustic touch prevents the arrangement from becoming overwrought, providing a crucial point of contrast. The song’s structure is classically simple—a short verse, a massive chorus, a brief bridge—but the sheer sonic force behind it makes it feel monumental. This dynamic interplay between Bonnet’s passionate urgency and the precise, opulent arrangement is the masterstroke of the recording.

This single was, in many ways, an anomaly, existing outside the context of a contemporary full-length album. The Marbles’ sole self-titled album wouldn’t appear until 1970, after the duo had already split, and largely served as a collection of their singles and B-sides. It was an epitaph, not a beginning. This 1968 release stood alone, an immediate, undeniable statement. It quickly became their one and only major hit.

The drama of the music mirrors the drama of the band’s fragmentation. The success of “Only One Woman” should have launched a sustained career. Instead, almost immediately following this breakthrough, creative tensions surfaced, exacerbated by a reportedly critical comment Bonnet made about the song itself. The follow-up single, another Gibb composition, “The Walls Fell Down,” did not repeat the massive international success. The Marbles disbanded in 1969, an extraordinarily short lifespan for a group that had delivered a song of this caliber. It became a classic ‘what-if’ moment in pop history.

For those of us obsessed with the architecture of classic recordings, “Only One Woman” remains a benchmark. It is a spectacular demonstration of how a brilliant composition, a powerhouse vocal, and an inspired orchestral vision can merge into a single, cohesive force. When listening today on modern premium audio equipment, the fidelity of the orchestral layers is remarkably clear, a testament to the quality of the original studio recording at IBC Studios in London.

“The emotional grandeur of this single transcends its one-hit-wonder status; it is a perfect artifact of its spectacular, ambitious moment in music.”

The song’s ability to connect persists precisely because of its high-stakes emotionality. We all have that one defining love, that one relationship that serves as the fixed point in our personal history, the one that makes the sweeping, dramatic claims of the lyrics ring true. This is why the song still works so well, whether heard in a quiet café or blasting from a car stereo on an empty highway. It is universal longing draped in lush, beautiful sound. It’s a tragedy compressed into two minutes and forty-three seconds of perfect, high-stakes pop. We remember The Marbles for this. Everything else is the winding road Graham Bonnet would later take toward heavy rock stardom.

Listening Recommendations

- The Bee Gees – “Massachusetts” (1967): Shares the same dramatic, orchestral ballad style and showcases the Gibb brothers’ early mastery of pop melodrama.

- The Moody Blues – “Nights in White Satin” (1967): For its sweeping strings, melancholic mood, and use of orchestral accompaniment to build emotional intensity.

- The Walker Brothers – “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” (1966): Features a similarly powerful, operatic lead vocal set against a colossal Wall of Sound-style arrangement.

- Gene Pitney – “Something’s Gotten Hold of My Heart” (1967): Another high-octane, soul-stirring ballad with huge production values and a deeply emotive male vocal performance.

- Scott Walker – “Joanna” (1968): Offers a comparable level of romantic, baroque-pop sophistication and vocal gravitas from the same period.

- The Grass Roots – “Midnight Confessions” (1968): For a slightly grittier, but equally brass and string-heavy, powerful single from the same transformative year.