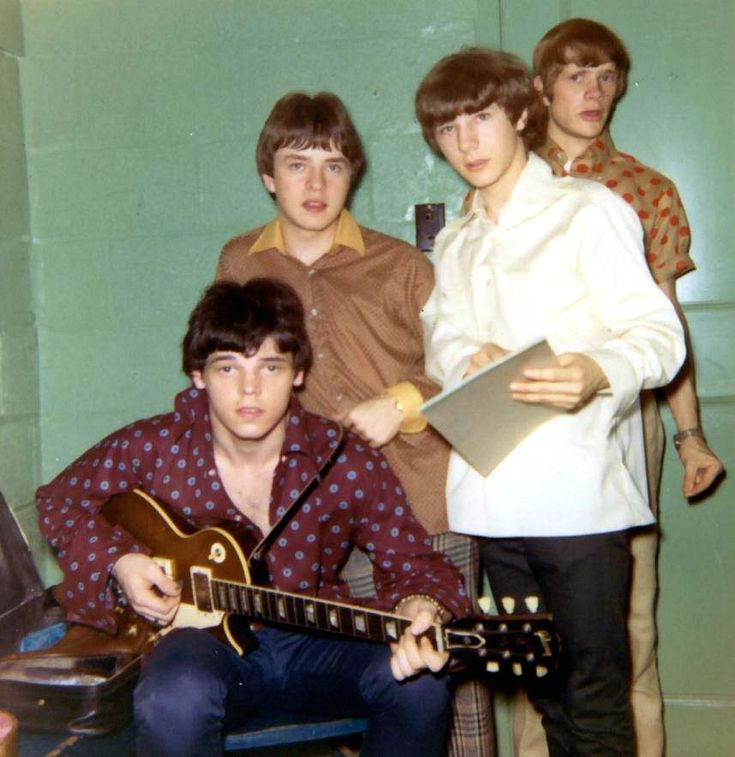

The air in 1965 was still thick with the residue of “Hang On Sloopy.” The song, a raw, infectious call-to-arms for every garage band with a cheap amp and a dream, had rocketed The McCoys from rural obscurity to the top of the American charts. It was a beautiful, accidental triumph—a perfect storm of a classic riff, a simple, irresistible chant, and the youthful swagger of a band fronted by a teenage guitar prodigy, Rick Zehringer (soon to be Rick Derringer). But the true test of a breakout act isn’t the single that makes them; it’s the one that follows.

Enter “Fever.”

This piece of music arrived in late 1965, reaching its chart peak in early 1966, an immediate and intentional follow-up to their massive success. It was released on Bang Records, an imprint deeply connected to Brill Building artistry, yet The McCoys, under the guidance of producers Bob Feldman, Jerry Goldstein, and Richard Gottehrer (known collectively as FGG, or The Strangeloves), had developed a sound that was pure Midwestern grit poured over slick New York hooks. “Fever” was featured prominently on their debut album, Hang On Sloopy, cementing their image as masters of the raucous cover.

But let’s be clear: covering “Fever” was a bold, almost reckless move. The standard, written by Eddie Cooley and Otis Blackwell (under the pseudonym John Davenport), was not just a song; it was a sacred text of cool. Little Willie John’s 1956 R&B original was all smoky, minor-key menace and finger-snap minimalism. Peggy Lee’s 1958 pop-jazz rendition elevated it to a high-lounge masterclass, all breathy control and detached glamour. The McCoys, a bunch of kids from Ohio, approached this monument of adult sophistication with a battering ram. The contrast is the song’s entire thesis.

The Attack: Sound and Instrumentation

The McCoys’ “Fever” is a study in purposeful contrast—glamour vs. grit. They retained the original’s minor-key structure and slow, slinky tempo, but amplified every other component by a factor of ten. The production is a marvel of mid-sixties garage engineering: slightly boxy, upfront, and driven by a desperate, palpable energy. Listening on studio headphones, the track feels claustrophobic, like being trapped in a sweaty, low-ceiling club.

The signature finger-snaps remain, but they are now backed by a rhythmic intensity that suggests anxiety, not seduction. The bassline, far from being a discreet anchor, is a prominent, throbbing counter-melody. The drums are loose, heavy on the tom-toms, and hit with a caveman aggression that immediately dismisses the polished coolness of the prior versions. This is not the heat of sultry romance; this is the heat of a dangerous illness.

The main event, of course, is the guitar work of Rick Zehringer. His approach is less about technical precision and more about sonic catharsis. While the Little Willie John version used Bill Jennings’ subtle, low-slung guitar phrases to accent the vocal, Zehringer’s guitar practically jumps out of the speakers, an untamed beast.

His main guitar riff, a sharp, repetitive minor-key figure, provides the song’s central tension. It’s dirty, compressed, and played with a restless vibrato that sounds less like a note and more like a feverish tremor.

The Derringer Edge: From Garage Licks to Hard Rock Phrasing

Zehringer’s vocal delivery is startlingly mature for a teenager. He leans into the lyrics, dropping the sultriness for a more aggressive, pleading tone. Yet, the real magic happens in the instrumental breaks. While there is no traditional piano on this track (opting instead for a raw, organ-less sound that strips away any remaining pretense of adult pop), the guitar fills the entire harmonic space.

The guitar solo, when it arrives, is brief but brilliant—a burst of raw, fuzzed-out energy that hints at the proto-hard rock legend Derringer would become. It’s not an exercise in melodic development; it’s a statement of raw, young, American power, echoing the primal, feedback-laced spirit of bands like The Yardbirds, but with a distinct, straight-ahead American rock flavour. The sound is dry and immediate, lacking the generous spring reverb one might expect from the era, lending the performance an almost documentary-like immediacy. This aesthetic choice is what separates The McCoys from the pop factory they were briefly affiliated with.

“The McCoys’ version of ‘Fever’ wasn’t a cover; it was an act of sonic vandalism that accidentally created a defining sound of mid-sixties American rock.”

The contrast in the performance is cinematic. Imagine the sophisticated black-and-white glamour of Peggy Lee suddenly exploding into the sticky, colour-saturated chaos of a teen dance floor, all flashing lights and cheap leather. The McCoys brought the song down to earth, giving the “cool” a palpable sense of danger and hormonal intensity.

Legacy and the Relisten

The McCoys never repeated the massive success of their first single, though “Fever” was a strong follow-up, peaking within the US Top 10. The band would later experiment with psychedelic and progressive rock before Rick Derringer’s ultimate pivot into a successful solo career and prolific session work. This “Fever” recording, however, remains a key artifact from their initial flash of brilliance—a moment when a band found a way to use a proven commercial formula (a cover song) to smuggle in their own raw, untamed identity.

It’s a foundational document for any guitar lessons enthusiast who wants to understand the evolution of the rock riff from rhythm and blues to the garage sound. The way Zehringer manipulates the sustain and attack of his instrument here is something that simply must be heard. For all its commercial intent, the final piece of music became something far more influential: a cornerstone of the garage-rock canon, a raw, exciting testament to the fact that youth culture always finds a way to take the established wisdom and turn up the distortion until it screams.

Listening Recommendations: Feverish and Fuzz-Laden Covers

- The Standells – “Dirty Water” (1966): Shares the same raw, immediate, and geographically specific garage rock production aesthetic.

- The Animals – “Boom Boom” (1964): Another classic R&B song given a driving, youthful urgency by a group with a powerful guitar sound.

- The Shadows of Knight – “Gloria” (1966): Features a similar primal energy and a simple, repetitive riff structure that defines the garage-rock sound.

- The Yardbirds – “I’m a Man” (1964): An early display of British R&B/rock where the guitar takes on a central, aggressive, and exploratory role.

- The Rolling Stones – “It’s All Over Now” (1964): An R&B cover that, like The McCoys’ “Fever,” successfully reinterprets the source material with a signature rock swagger.

- The Kinks – “All Day and All of the Night” (1964): Features one of the earliest examples of a heavily fuzzed, driving guitar sound that The McCoys channel.