The year 1967 was already a kaleidoscope of noise and light, a summer so saturated with change that every song felt like a flag being planted. Yet, in the midst of the Summer of Love’s psychedelic swell, The Monkees—the band whose very existence was a corporate lightning rod for authenticity debates—dropped a single that delivered a critique sharper than a newly-sharpened kitchen knife. That single was “Pleasant Valley Sunday,” and it remains, nearly six decades on, a fascinating, crucial pivot point in their career and in the annals of smart pop.

We begin not in the studio, but in a world of manicured uniformity: the suburbs. The song, penned by the legendary Carole King and Gerry Goffin, was a direct response to Goffin’s own disquiet after he and King moved to West Orange, New Jersey. The lyrics are a masterpiece of polite, domestic dread, painting an image of “rows of houses that are all the same” where Mrs. Gray is preoccupied with her roses and Mr. Green is “so serene” with a television in every room. It’s a quiet scream against “status symbol land,” a world where the creature comfort goals numb the soul.

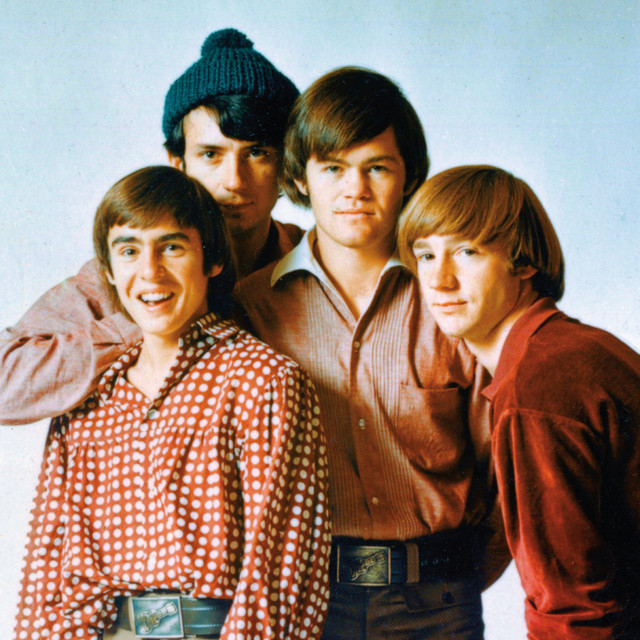

The Monkees were, at this point, fresh off a successful revolt against their initial “manufactured band” image. They had, famously, taken creative control from their music supervisor Don Kirshner, culminating in the organic, self-penned sound of their third album, Headquarters. “Pleasant Valley Sunday,” released in July 1967, served as a crucial bridge. While it was released as a single, it was also the standout track on their fourth album later that year, the wonderfully titled Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd. This single was a demonstration of the Monkees’ newfound power, showing they could leverage the best songs from outside writers (like Goffin/King) while ensuring their own members—specifically Michael Nesmith and Micky Dolenz—were integral to the execution.

It was producer Chip Douglas (formerly of The Turtles) who helped shape the sound, creating an arrangement that perfectly weaponized the Goffin/King lyric. The track doesn’t sound like a protest song; it sounds like a vibrant, swirling Sunday afternoon fever dream.

The Riff That Rewrote The Monkees’ Credibility

The sonic identity of this piece of music is impossible to separate from its opening salvo: Michael Nesmith’s instantly recognizable electric guitar riff. It’s a snaking, Mixolydian-tinged figure—reportedly inspired by The Beatles’ “I Want to Tell You”—that grabs the listener by the lapels and refuses to let go.

The riff is tight, dry, and delivered with a confidence that immediately silences the old “they don’t play their instruments” canard. Nesmith, using a Gibson Les Paul through three Vox Super Beatle amplifiers, achieves a clean yet authoritative tone that provides the song’s driving rhythm. It’s clipped and precise, contrasting beautifully with the hazy, psychedelic textures that emerge later. This is the sound of a garage band, yes, but a garage band with the best songwriting in the business and a producer who knows exactly how to frame them.

“The best social commentary always comes wrapped in the catchiest possible tune.”

The main body of the song sits in a crisp, energetic arrangement. Micky Dolenz and Nesmith’s unison lead vocals have a casual, slightly cynical drawl that fits the lyrical observation perfectly. Underneath the vocals, the instrumentation is deceptively dense. Peter Tork is often cited as contributing the subtle, yet essential, low-end pulse on piano and perhaps other keyboards, underpinning the sharp rhythm section provided by Douglas on bass and Eddie Hoh on drums. The overall sonic picture is bright, punchy, and utterly dynamic, a million miles away from the session-musician predictability that characterized some of their earliest material.

The Whirlpool of Status Symbol Land

The song’s structure is classic pop, built on propulsive verses and a sing-along chorus, yet it’s the instrumental break and the coda that elevate it to a minor masterpiece of psychedelic pop.

In the middle eight, the song modulates, lifting the mood momentarily before Dolenz and Nesmith deliver the famous, almost nonsensical, “Goo goo, goo goo, joob joob” backing vocal counterpoint. This sequence adds a layer of surrealism, a momentary sonic escape from the “rows of houses.” It’s a flash of pure 1967-era whimsy that gives way to the song’s true brilliance: the fade-out.

As the band drives the central riff repeatedly into the ether, Douglas and engineer Hank Cicalo employ an extreme manipulation of sound. They reportedly “kept pushing everything up,” using increasing amounts of reverberation and echo until the track dissolves into a chaotic, whirling vortex of noise and texture. The drums become blurred; the guitar riff becomes an unrecognizable, echoing siren; the whole mix collapses into pure sound. This is not just a standard fade; it’s a terrifying, beautiful disintegration, a sonic metaphor for the soul-numbing conformity the lyrics decry. The pleasant valley is literally imploding under the weight of its own empty status symbols.

For those who take their deep listening seriously, the complexity of this sound engineering is a masterclass. You might even want a pair of studio headphones to fully appreciate the depth of that final, spiraling reverb tail. It speaks to a level of studio craft that The Monkees, by 1967, were now demanding and achieving, proving they were far more than a simple TV act.

This song isn’t just a record; it’s a time capsule. I remember being a kid, hearing it on a crackly AM radio driving through a subdivision that looked exactly like the one Goffin and King wrote about, and suddenly, the houses seemed to ripple with a shared, unspoken dread. The cheerful, upbeat melody acts as a Trojan Horse for a profoundly subversive message—a pop hit that mocks the very audience it seeks to entertain.

It’s a micro-story that plays out every day: the young local rock group, down the street, trying to learn their song, while the weekend squire mows his lawn, oblivious to the fact that his “serenity” is being serenaded by an anthem of his own cultural incarceration. It’s the sound of the youth rebellion sneaking onto the Billboard charts dressed up in a bright, premium audio pop outfit. This masterful piece of music stands not as an artifact of pop music history, but as an enduringly relevant piece of social art.

The song ultimately peaked high on the US charts, securing its place as one of the band’s most recognizable and important hits. It cemented The Monkees’ reputation as both genuine rock artists (at least in their execution and intent) and as a reliable vehicle for the era’s most incisive songwriters. It is the perfect blend of brilliance: a Goffin/King composition delivered with the necessary rock grit and psychedelic flourish by the most unlikely—and ultimately, most compelling—band of the era. A re-listen, especially focusing on that final dissolve, is a must.

Listening Recommendations

- The Beatles – “I Want to Tell You” (1966): Shares the quirky, Mixolydian-tinged guitar riff inspiration cited by the song’s producer.

- The Turtles – “Happy Together” (1967): Features a similarly bright, punchy Chip Douglas production and optimistic-sounding pop structure.

- The Kinks – “Dead End Street” (1966): Another sharp social commentary track from the same era, focusing on the drabness of everyday life.

- The Beach Boys – “Good Vibrations” (1966): For the inventive, multi-part structure and the extreme, layered studio techniques used in the complex arrangement.

- Carole King – “It’s Too Late” (1971): Hear the original songwriter’s mature, introspective style that was forged, in part, by her earlier work for The Monkees and others.

- The Grass Roots – “Midnight Confessions” (1968): A high-energy, horn-driven pop track demonstrating a similar mid-to-late 60s pop production sensibility.