The radio dial was turning. It was late, the kind of hour where AM static breathes louder than the music. For most of the decade, The Monkees were defined by a certain primary-color pop—a perfect, glossy confection spun for a hungry Saturday morning audience. Their music was bright, a sonic equivalent of a cartoon chase scene, engineered by the brightest minds in the Brill Building machine. But then, the dial would sometimes catch something else, a different frequency entirely.

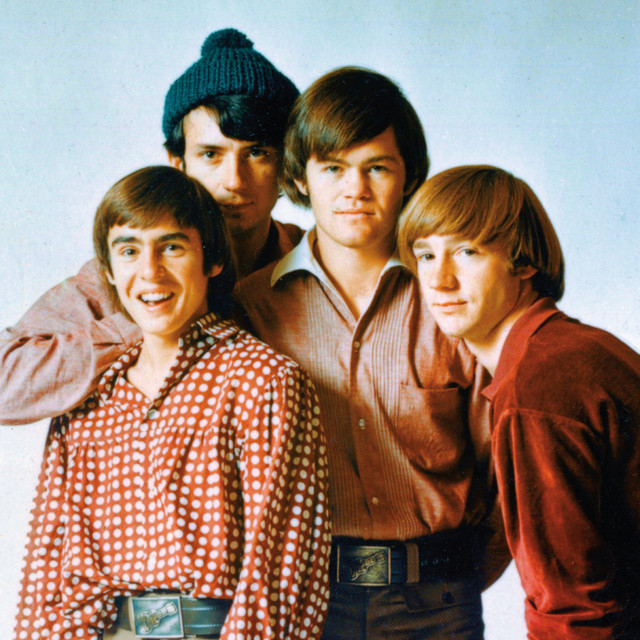

This was 1967, and the air was thick with change, not just in the cultural landscape, but in the power dynamics of the music industry. The Monkees—Micky, Davy, Mike, and Peter—were in the throes of their famous, fraught, and ultimately successful rebellion. They had wrestled control from Don Kirshner, insisting on playing their own instruments, writing their own songs, and guiding their own sound. This transition, this assertion of artistic identity, is crystallized in their third album, Headquarters. It’s a document of a band finally becoming a band.

But even on this deeply personal, self-piloted album, a strange, sophisticated ghost flickers in the tracklist. It’s a composition that feels too world-weary for a group famous for high-energy farce: “Shades of Gray.”

It’s an outsider piece of music, written not by a Monkee, but by the legendary Brill Building duo of Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, which only adds a fascinating layer of complexity to the narrative of autonomy. The Monkees, having fought to make their own music, chose to record this deeply complex, downbeat song, which speaks volumes about the emotional maturity they sought to project. Its inclusion on Headquarters acts as a crucial bridge, linking their past life of polished pop to their burgeoning future of self-determination.

The recording itself, produced by Chip Douglas, stands apart from the rest of the mostly self-performed Headquarters. While the band members do contribute—Peter Tork’s crucial, melancholic piano chords, Michael Nesmith’s distinctive pedal steel guitar texture, and the shared lead vocals of Peter and Davy Jones—this track uniquely features an outside cellist and French horn player, adding an undeniable, refined depth. The presence of these outside musicians, precisely for a few baroque touches, emphasizes the track’s ambition to be something more than garage rock or bubblegum.

From the first sustained chord, the song settles into an atmosphere of profound, gentle resignation. It’s slow, almost funereal, a lullaby for a conscience losing its clarity. The arrangement is magnificent and sparse. The French horn, played by Vincent DeRosa, doesn’t blare in a triumphant fanfare; it lingers, a warm, mournful drone beneath the fragile melody, adding a rich, burnished timbre. The cello, played by Frederick Seykora, traces a graceful counter-melody, a weeping undercurrent that elevates the track into pure chamber pop territory.

It is Tork’s piano, however, that holds the song’s emotional center. His chords are simple, resonant, and widely spaced, creating an echo of doubt in the room. This isn’t the flashy rock and roll piano of Little Richard; it’s the contemplative, classical voicing of a musician sitting alone, grappling with unanswerable questions. The sonic texture is intimate, as if we are leaning in close to a high-quality set of premium audio speakers, catching every breath and the subtle decay of the notes.

The lyrics, in their profound simplicity, are the song’s true masterstroke. They document the moment a young person realizes that the world they were promised—a world of black and white, right and wrong—simply doesn’t exist. “When the world and I were young / Just yesterday / Life was such a simple game / A child could play,” Davy Jones sings, his voice surprisingly mature, tinged with a delicate, English melancholy.

This is immediately followed by Peter Tork’s more gravelly, world-weary delivery in the bridge: “But the years have come between / To confuse my mind / And the dreams that I was chasing / Are not easy now to find.” The dual lead vocal—Jones’s wistful innocence contrasting with Tork’s somber reflection—is the perfect dramatic device. It’s the dialogue between the man we were and the man we are forced to become.

The bassline is quiet but essential, anchoring the sophisticated ornamentation above it with a steady, walking pattern that feels almost like a heartbeat. Michael Nesmith’s pedal steel guitar is an inspired choice. Its gliding, weeping quality adds a country-folk flavor that subtly pushes against the baroque chamber elements, lending an American grit to the European classicism. This juxtaposition—horn and cello meeting steel guitar—is what makes “Shades of Gray” so uniquely moving.

The dynamics are handled with restraint. The song never explodes into a loud chorus; instead, it builds tension through texture and harmony. The strings swell momentarily, then recede, leaving the listener suspended in a state of quiet contemplation. It’s a masterful exercise in restraint, a refusal to offer easy catharsis.

In 1967, a year defined by kaleidoscopic color and psychedelic explosion, this song was a voluntary retreat into quiet introspection. It’s a three-minute meditation on moral relativism in an era that desperately needed heroes and villains. The Monkees, as performers, prove their mettle by embodying this quiet doubt so convincingly. It’s a testament to their desire to be taken seriously, to show that their talent extended far beyond the confines of a TV script. They were seeking, and ultimately finding, the moral ambiguities of life in their own sound.

“It is a sound that captures the exact moment the world stops being simple, and all the sharp, hard edges of youth begin to blur.”

This piece of music resonates deeply because that transition from simple faith to complicated doubt is universal. We all have that moment: the realization that the sheet music of life isn’t written in a clear major key but is instead layered with unexpected chromatics and dissonances. The song captures the feeling of looking back at a childhood home and understanding you can never fully go back. It’s a necessary farewell to a comfort that was ultimately an illusion. This depth ensures its continued relevance, long after the TV show has become a historical footnote. It’s a reminder that authenticity, for an artist, is often found not in volume, but in vulnerability.

Listening Recommendations (For Adjacent Moods and Arrangements)

- The Beatles – She’s Leaving Home (1967): Shares the same year and the effective, wistful use of chamber orchestration (harp, strings) to underscore a domestic tragedy.

- The Zombies – A Rose for Emily (1968): Another example of delicate, melancholic baroque pop with superb vocal harmonies and an atmosphere of gentle, haunting sadness.

- The Turtles – Guide for the Married Man (1967): Produced by Chip Douglas, it showcases a similar light touch in arrangement and a sophisticated, adult sensibility in its pop frame.

- Love – Andmoreagain (1967): A softer moment from the Forever Changes album, built on acoustic guitar and strings, capturing a similar sense of fragile beauty and introspection.

- The Left Banke – Walk Away Renée (1966): The blueprint for the chamber pop sound, featuring harpsichord and strings, with a timeless, romantic melancholy.

- Simon & Garfunkel – Old Friends (1968): Focuses on the quiet sadness of time’s passing and lost simplicity, carried by acoustic guitar and gentle orchestral accents.