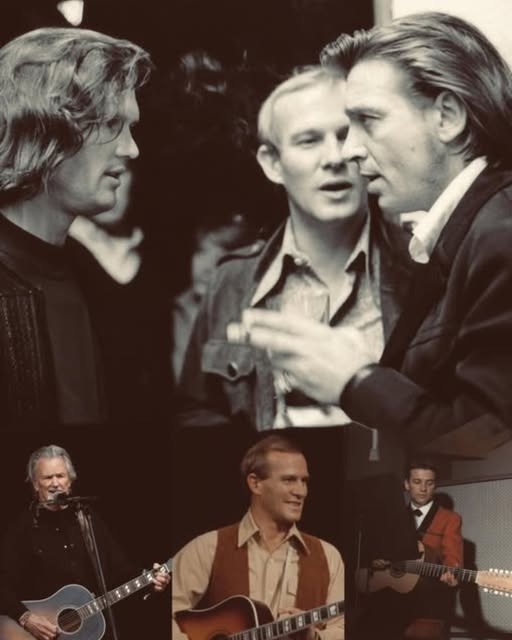

It’s a wild and beautiful thought that the same rebellious spark can live in three different forms at once: in a poet who bleeds onto the page, an outlaw who kicks down industry doors with a guitar, and a comedian who smuggles truth into the room with a joke. In the late 1960s and 1970s, that fire burned inside Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and their close friend Tom Smothers. Different stages, different tools—but the same refusal to lie about life.

Country music has always been a home for honesty, but this trio pushed that honesty into the open, even when it made people uncomfortable. Jennings fought the polished, assembly-line sound of the Nashville system and helped ignite what would become known as the outlaw movement—music that sounded like the road, the barroom, and the back of a long night. Kristofferson wrote songs that felt less like compositions and more like confessions. Smothers, on television, proved that a punchline could carry the same weight as a protest sign. Together, they embodied a dangerous idea: that art doesn’t have to be clean to be true.

Three Voices, One Truth

What bound these men together wasn’t just friendship—it was a shared hunger for unfiltered truth. Waylon’s voice came out gravelly and defiant, like he’d already lived the consequences of every lyric he sang. Kris wrote lines that didn’t apologize for loneliness, addiction, regret, or shame; he named them and let them breathe. Tom used comedy to poke holes in power and pretense, slipping hard truths past censors with timing and charm.

In different languages—music, poetry, and laughter—they were saying the same thing: don’t dress up pain to make it palatable. Say it the way it feels. Let it land where it lands.

“Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” — When Honesty Refused to Be Polite

If you want to hear that philosophy crystallized into three minutes of devastating beauty, you land on Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down. Written by Kristofferson, the song doesn’t romanticize the morning after. It wakes up with a hangover, walks empty streets, and stares into the quiet shame of being alone while the world seems to move on without you. There’s no grand metaphor to hide behind. Just cold pavement, church bells, and the ache of realizing you’ve drifted from the life you imagined.

The song’s power comes from its refusal to polish the edges. It names the small humiliations—watching people with purpose while you stand still, feeling time move forward without you—and somehow makes them feel universal. Anyone who has ever woken up on the wrong side of their own choices hears themselves in it.

When Television Tried to Blink—and Didn’t

The truth of “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” nearly hit a wall when Johnny Cash took the song to national television. Network executives reportedly wanted him to soften the lyric about “wishing, Lord, that I was stoned.” Cash refused. The line stayed.

It was a small moment with a long shadow. In an era when country music on TV was expected to be tidy and respectable, Cash insisted that truth didn’t need permission. The performance felt like a quiet rebellion—no shouting, no grandstanding, just a man standing still and letting the words cut through the room. In that moment, Kristofferson’s confession became a public one. Millions heard a piece of themselves in it, even if they didn’t want to admit it.

Why This Song Still Hurts in the Best Way

Decades later, “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” still lands with the same ache because it doesn’t pretend pain is temporary or tidy. It doesn’t promise redemption by the final chord. It simply sits with you in the mess and says: this is real.

That’s why it continues to feel modern. In a culture obsessed with highlight reels and curated happiness, the song offers the opposite—a mirror for the mornings when you’re not okay and don’t know how to fix it yet. Kristofferson didn’t write a hymn to despair; he wrote a document of being human. And humans, it turns out, don’t age out of loneliness.

The Outlaw Spirit That Refused to Behave

Waylon’s role in this story matters because he proved that the music industry itself could be challenged. He didn’t just sing about freedom—he fought for it in contracts, in sound, in image. The outlaw movement wasn’t about being rebellious for style points; it was about taking back control of the story. That spirit gave space for songs like “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” to exist without apology.

And Smothers, in his own lane, showed that even laughter could carry a blade. Comedy could expose hypocrisy. Jokes could open doors that speeches couldn’t. Together, these three artists expanded what “truth” could look like in American culture. It could be sung. It could be written. It could be laughed into the room.

Art That Tells the Truth Stays

Trends come and go. Sounds evolve. But art that tells the truth sticks around because people keep needing it. Every generation wakes up to its own version of a lonely Sunday morning. Every generation has its own polished lies to peel back.

That’s why Kristofferson’s song still finds new listeners. That’s why Waylon’s outlaw growl still sounds like permission to choose your own road. And that’s why Tom Smothers’ brand of fearless humor still feels relevant: because the work they did wasn’t about a moment—it was about a way of seeing.

In the end, the rebellious fire that united a poet, an outlaw, and a comedian didn’t burn to shock. It burned to reveal. And what it revealed was simple, uncomfortable, and timeless: truth doesn’t need makeup. It just needs a voice brave enough to say it out loud.